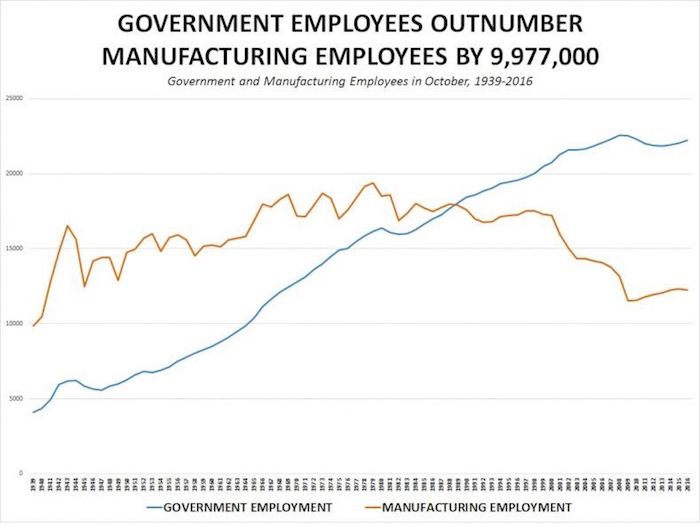

Nearly twice as many work in government as in manufacturing

Terence Jeffrey reports the latest data:

The United States lost 9,000 manufacturing jobs in October while gaining 19,000 jobs in government, according to data released by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Government employment grew from 22,216,000 in September to 22,235,000 in October, according to BLS, while manufacturing jobs dropped from 12,267,000 to 12,258,000.

This chart plots the number of manufacturing employees against the number of government employees:

No wonder economic growth has slowed to a crawl!

Of course, the decline in manufacturing jobs doesn’t necessarily mean a decline in manufacturing. On the contrary, the value of goods made in America is higher than ever. But greater efficiency means that more goods can be produced with less labor. This is similar to what happened in agriculture, a generation earlier: there are vastly fewer farmers today than there were a century ago, but far more crops and animals produced. The good news is that the average job in manufacturing or agriculture pays far better than it did decades ago, as workers reap the benefit of greater productivity.

Still, workers need jobs. Better government policies would enable more manufacturing, and more manufacturing jobs, in the U.S.

Looking at the chart above, one naturally wonders when government will experience the same sort of productivity revolution that came to agriculture and manufacturing. When will we see better government with fewer public employees?

Perhaps never. Government, generally speaking, is a monopoly. Without competitive pressure, there is little incentive to improve productivity. On the contrary, there is a huge disincentive to cutting government payrolls.

Many people don’t seem to realize that government itself has become a special interest–by far the largest, and potentially most destructive, special interest group of them all. Government’s interests are promoted in part by government workers voting for political candidates who promise to spend more money. (To their credit, there are many public employees who do not vote for more government, but they are a minority.) And public employee unions are by far the largest funders of political campaigns–virtually always supporting candidates who call for more government.

Those who are in charge of government at all levels would generally prefer to see more employees, not fewer, and higher costs, not lower. Unlike the private sector, those who run governments do not bear the consequences of higher costs. Taxpayers do. Until taxpayers get serious about restraining the size and cost of government, look for the number of public employees to continue to rise.