MN Sheriff Uses Obscure State Law to Take Over Wolf Kill Investigations

The argument over the sustainability of northern Minnesota’s wolf population ended long ago, at least among the folks who live there. The latest proof of proliferation comes from an extraordinary photo in the Echo Press of a 100 pound wolf roadkill north of Alexandria in west central Douglas County documented by a local deputy.

Alexandria and areas to the north such as Parkers Prairie and Fergus Falls are not within the current borders of what is considered wolf range in Minnesota. However, the last time those borders were examined was the winter of 2012-2013.

In an interview, DNR wolf research scientist John Erb said it would not surprise him if wolves, once an endangered species, have been sighted in an area like this outside of their established range farther north.

Yet Minnesota remains under the thumb of a federal court order that rescinded a successful state management program predicated on limited hunting and taking of problem wolves by farmers.

As a result, the state’s wolf population shot up 25 percent in the last count. Not surprisingly the number of dead livestock from wolves surpassed the previous year’s total by mid-October 2017.

While federal agents or state game wardens typically investigate suspected wolf kills of livestock, MPR reports one northwestern Minnesota sheriff has taken matters into his own hands. The recently appointed lawman may be the only sheriff to invoke a 2010 state law that empowers sheriffs to look into wolf predation.

Sheriff Steve Porter is stepping into the long-running conflict over wolf management in Minnesota.

Ranchers in Kittson County are frustrated and angry, he said, and they need someone to stand up for them.

“They don’t want to be the voice for the problem, but they’re upset about the problem. So when I talk to these guys, boy, they’re bending my ear telling me this is a problem,” Porter said. “And if I can use my voice to influence and get this changed back, I would like to do that.”

Federal and state agents find wolves responsible for livestock kills about half the time. But Porter’s investigations link wolves to the death of farm animals at a much higher rate, resulting in more farmers receiving compensation for their loss.

In Kittson County, Porter is aggressive with his investigations. This fall, a farmer called the sheriff to report two calves missing. He couldn’t find them and didn’t have time to look because he was in the middle of corn harvest.

“Two deputies went out there, got ATVs, spent three or four hours in his pasture. And what did they find? Two dead calves, torn apart by wolves,” said Porter. “The deputies signed off, called the federal trapper. He went out and caught two or three wolves on that property.”

And the farmer got paid for the missing calves. While ranchers can’t legally kill a wolf preying on their livestock, if a kill is confirmed, a federal trapper will try to remove wolves from the area.

Yet Porter says the current system falls far short of reimbursing farmers for their actual losses.

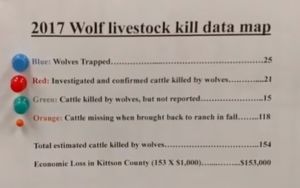

In the past six years, Kittson County ranchers submitted claims for 45 wolf kills. The state paid nearly $60,000 in compensation.

Porter believes the losses are much greater. His office interviewed 40 farmers who raise cattle on pastures. They identified 118 missing calves when cattle were brought in from pastures this fall.

“You don’t even find a bone. That’s consistent with the wolf kill and so their best guess is they’re missing 118 calves,” Porter said. “They don’t get compensated for that. That’s a big hit.”

Porter puts the uncompensated loss to ranchers at more than $118,000.

For now, the Kittson County sheriff’s office appears to be filling the gap between federal policy and reality on the ground. But the increasing number of wolves and dead livestock, along with the inability of farmers to do anything legally about it, means something ultimately will have to give.