Milton Friedman: Politics and Violence

In the most recent edition of our magazine Thinking Minnesota, I have an article on the tumultuous year of 1968. I was struck, when researching and writing it, how many parallels there are with the contemporary situation in the United States.

In the most recent edition of our magazine Thinking Minnesota, I have an article on the tumultuous year of 1968. I was struck, when researching and writing it, how many parallels there are with the contemporary situation in the United States.

This struck me again as I read the column below written by the economist Milton Friedman for Newsweek in June of that year. As government in America has grown bigger and assumed power over more and more of our lives, people on both sides of the political divide either look to it to further their agenda, if their party is in power, or view it as a threat to their way of life if it isn’t. As Friedman explains, government is about conformity. As it grows, the space for us to live and let live shrinks. In a vast, sprawling, diverse country such as the United States, that is a recipe for trouble now, just as it was 50 years ago.

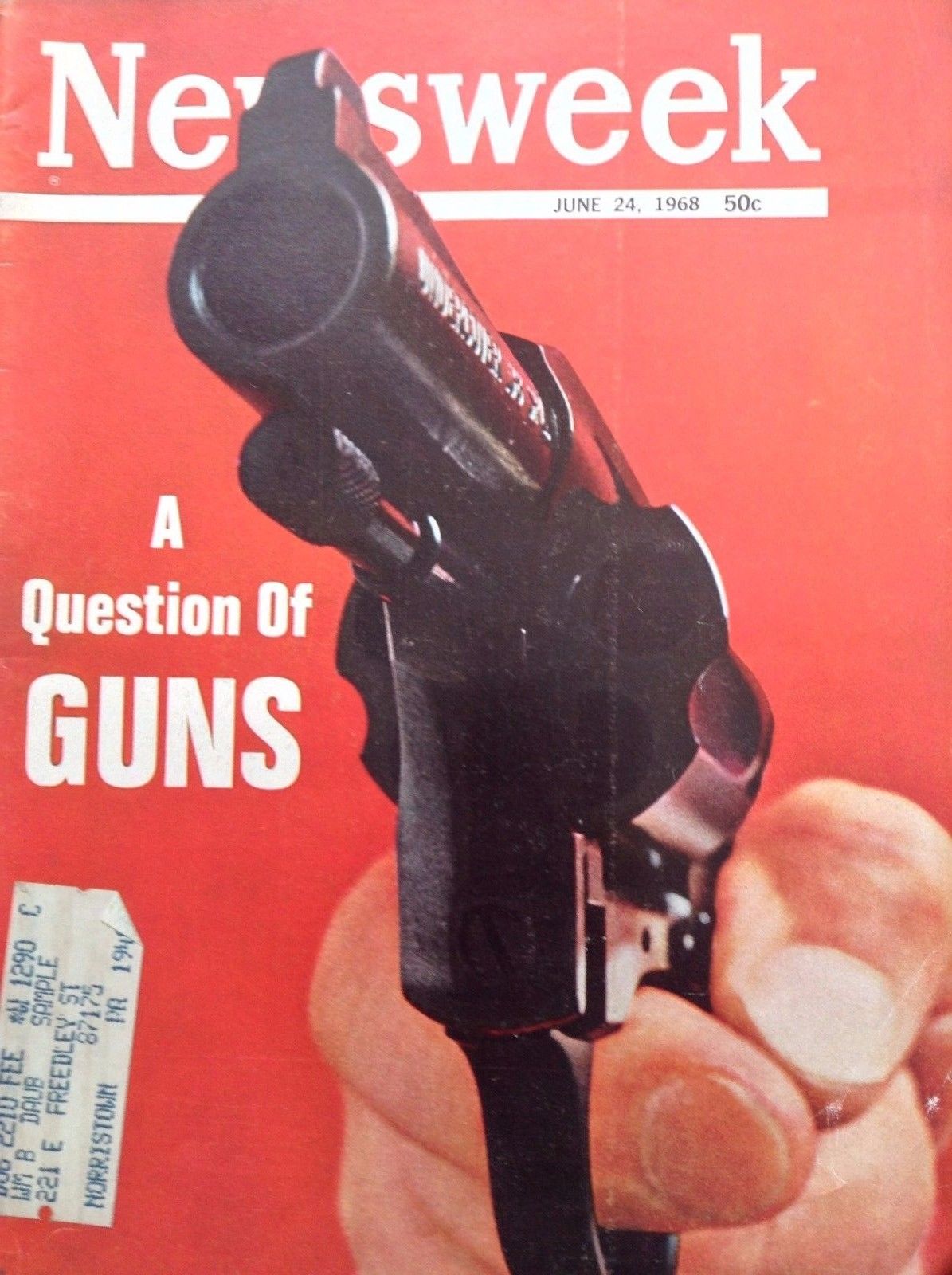

Politics and Violence, Milton Friedman, Newsweek, June 24th, 1968

There is no simple, widely accepted explanation for the increasing violence that is disfiguring our society. That much is clear from the public soul-searching renewed by the tragic assassination of Robert Kennedy.

This soul-searching has touched on many plausible contributing factors–from the malaise over Vietnam, and racial unrest to the boredom produced by affluence. But it has neglected one factor that underlies many specific items mentioned. That factor is the growing tendency, in this country and throughout the world, to use political rather than market mechanisms to resolve social and individual problems.

The tendency to turn to the government for solutions promotes violence in at least three ways:

1. It exacerbates discontent.

2. It directs discontent at persons, not circumstances.

3. It concentrates great power in the hands of identifiable individuals.

1. The political mechanism enforces conformity. If 51 per cent vote for more highways, all 100 per cent will have to pay for them. If 51 per cent vote against highways, all 100 per cent must go without them.

Contrast this with the market mechanism. If 25 per cent want to buy cars, they can, each at his own expense. The other 75 per cent neither get nor pay for them. Where products are separable, the market system enables each person to get what he votes for. There can be unanimity without conformity. No one has to submit.

For some items, conformity is unavoidable. There is no way that have the size of U.S. armed forces I want while you have the size you want. We can discuss and argue and vote. But having decided, we must conform. For such items, use of a political mechanism is unavoidable.

But every extension–and particularly every rapid extension–of the area over which explicit agreements is sought through political channels strains further the fragile threads that hold a free society together. If it goes so far as to touch an issue on which men feel deeply yet differently, it may well disrupt the society–as our present attempt to solve the racial issue by political means is clearly doing.

2. If a law, or action by a public official, is all that is needed to solve a problem, then the people who refuse to vote for the law, or who fail to act, are responsible for the problem. The aggrieved

persons will naturally attribute to malevolence the failure of others to vote for the law, or of civil servants to act.

A specific problem often can be resolved by a law–generally one that imposes costs on some to benefit others. But along this road, there is no end to demands. These will inevitably call for more than the total of the nation’s resources–however ample they may be.

Circumstances–the fact that resources are limited–make it impossible to meet all demands. But to each citizen it will appear–often correctly–that he is being frustrated by his fellow men, not by nature. Men have always reached beyond their grasp–but they have not always attributed failure to the selfishness of their fellow men.

France is today a striking example–of both escalating demands and the personalizing of discontent.

3. Political power is not only more visible but far more concentrated than market power can ever be.

The Kennedy family is a harrowing example. Joseph P. Kennedy amassed a fortune of hundreds of millions of dollars. Yet he never had power of a kind to tempt anonymous assassins. Two sons have been assassinated, one at the pinnacle of political power, the other at the beginning of a great political career.

To put it objectively, had the Kennedy fortune never been amassed, the effect on the history of the world would have been trivial–except that it would have been more difficult for his sons to pursue political careers. The assassination of the two sons may well change the history of the world.

A free and orderly society is a complex structure. We understand but dimly its many sources of strength and weakness. The growing resort to political solutions is not the only and may not be the main source of the resort to violence that threatens the foundation of freedom. But it is one that we can do something about. We must husband the great reservoir of tolerance in our people, their willingness to abide by majority rule–not waste it trying to do by legal compulsion what we can do as well or better by voluntary means.

John Phelan is an economist at the Center of the American Experiment.