Minnesota spends less than the U.S. generally on research and development. How can state tax policy help?

Yesterday, I wrote about how Minnesota had the the 36th fastest growing economy in the United States in the first quarter of 2019. Our economy grew at 2.6% in real terms, below the national rate of 3.1%. This is the third consecutive quarter in which Minnesota’s economy has grown more slowly than that of the United States generally. Over that period, the U.S. economy has grown by 9.0% in real terms, while ours has grown by 6.3%.

If you have read our annual reports on Minnesota’s economy, you might not find this so surprising. In 2016, we called Minnesota’s economic performance ‘mediocre‘. In 2017, we said it was ‘lackluster‘. In 2018, we said it was ‘unimpressive‘. You get the idea.

There are a number of factors behind this. One of which, is the state’s low level of Research & Development (R&D) spending, relative to the U.S. average. R&D can be seen as improving the quality of physical capital.

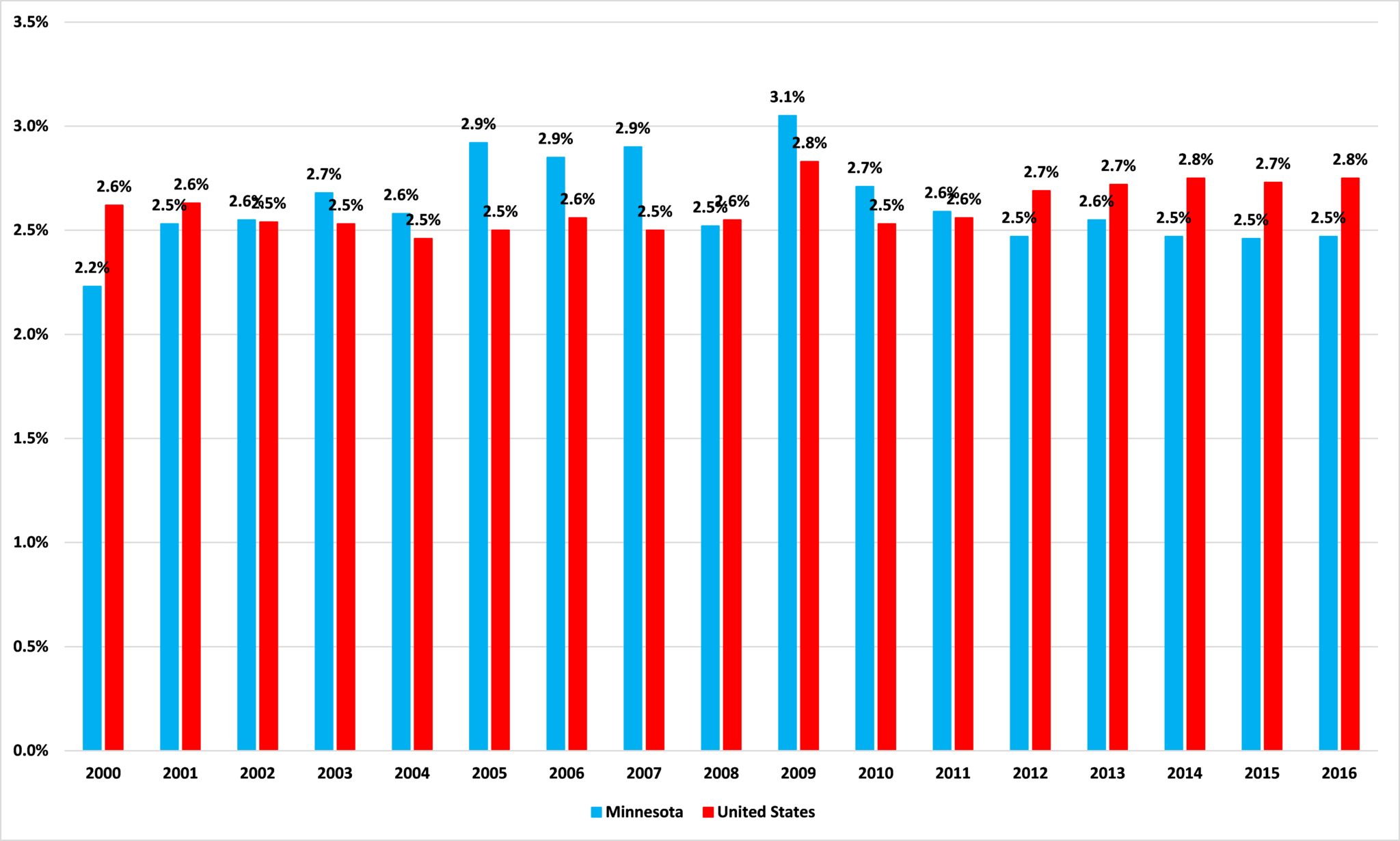

Figure 1 shows the R&D intensity for Minnesota and the national average. This is the ratio of total R&D performed in a state to its state Gross Domestic Product (GDP). It may come as a surprise to Minnesotans who are apt to think of their state as a technology leader, but the state currently lags the national average on this measure of R&D spending. Between 2003 and 2011, as a share of GDP, Minnesota devoted more resources to R&D than the national average. But since 2012, our state has lagged the nation. In 2016, the figure for the U.S. was 2.75 percent, in Minnesota it was 2.47 percent.

Figure 1: Research and Development Intensity, 2000-2016

Source: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and National Science Foundation’s National Patterns of R&D Resources

What can we do about this?

In a recent paper for the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) titled ‘Taxation and Innovation‘, economists Ufuk Akcigit and Stefanie Stantcheva found that “taxation of both corporate and personal income negatively affects the quantity, quality, and location of innovation at the state level and the individual inventor and firm levels.”

In another recent NBER paper, ‘Tax Policy for Innovation‘, economist Bronwyn H. Hall reviews the empirical evidence on the effectiveness of tax incentive to encourage firms to undertake innovative activity. She writes,

The two key tax policies that bear directly on innovative activity are various R&D tax credits and super deductions for R&D expense (cost reduction for an innovative input) and reduced taxes on profits from intellectual property (IP) income, commonly known as an IP box.

Hall finds that “evidence on the effectiveness of R&D tax credits has accumulated to show that they are generally effective at increasing business R&D”.

Minnesota is one of the highest taxed states in America. Research shows that these high tax rates disincentivize R&D. And the data shows that our state lags the national average on R&D spending. It is hard to avoid the conclusion that Minnesota’s high taxes are deterring R&D in the state. To get that investment up, we need to get those rates down.

John Phelan is an economist at the Center of the American Experiment.