The Lesson of Prohibition

This article originally appeared in the Fall 2019 issue of Thinking Minnesota, now the second largest magazine in Minnesota. To receive a free trial issue send your name and address to [email protected].

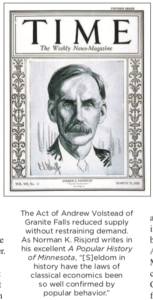

The cover of the March 29, 1926 edition of Time featured Andrew Volstead, a humble lawyer from rural Granite Falls, Minnesota. Until 1922, he had been the Representative for Minnesota’s 7th Congressional District, rising during his term to become chairman of the House Judiciary Committee. And, in that capacity, he gave his name to one of the most notorious pieces of legislation in American history. The Volstead Act—formally known as the National Prohibition Act—passed into law in October 1919 and prohibited the manufacture and sale of alcoholic beverages.

The cover of the March 29, 1926 edition of Time featured Andrew Volstead, a humble lawyer from rural Granite Falls, Minnesota. Until 1922, he had been the Representative for Minnesota’s 7th Congressional District, rising during his term to become chairman of the House Judiciary Committee. And, in that capacity, he gave his name to one of the most notorious pieces of legislation in American history. The Volstead Act—formally known as the National Prohibition Act—passed into law in October 1919 and prohibited the manufacture and sale of alcoholic beverages.

“On Tuesday next the United States will go dry—the first great nation to undertake this stupendous experiment in behalf of public morals,” the Pioneer Press wrote. “It has been the experience of those cities that have tried Prohibition that crime—petty crime, that is—declines under a dry regime.” The article went on, “The probabilities are, however, that little by little everybody will become accustomed to the new order. …The best thing for the United States to do is forget as quickly as possible that it ever enjoyed the stimulation of alcohol.”

The Pioneer Press was wrong. History remembers Prohibition as one of the great failures of American public policy. It failed to end the consumption of alcohol in America—economist Clark Warburton estimated that in 1929 alcohol consumption was 70 percent of pre-Prohibition rates. And it failed at great cost. While federal spending on enforcement was never a large share of overall spending—less than 1% in 1929, for example—the vast returns to the illegal production and distribution of alcohol (bootlegging) caused a surge of violence across the country. The economist Burton A. Abrams estimates that Prohibition resulted in 29,000 homicides, “roughly equal to the American lives lost in the Korean War.”

The Act of Andrew Volstead of Granite Falls, which placed him on the cover of Time magazine, reduced supply without restraining demand. As Norman K. Risjord writes in his excellent A Popular History of Minnesota, “[S]eldom in history have the laws of classical economics been so well confirmed by popular behavior.”

Prohibition destroys the brewing industry

The first thing Prohibition did was destroy the legal brewing industry.

Minnesota’s Germans brought with them a long brewing tradition. Water was plentiful, and the landscape lent itself to growing hops and barley. Bavarian immigrant Anthony Yoerg opened Minnesota’s first “commercial” brewery in 1849. Other German immigrants became famous as brewers, such as Jacob Schmidt, Theodore Hamm, and Gottlieb Gluek, whose name lives on in a bar on North 6th Street in Minneapolis. At the dawn of Prohibition, Minnesota, with 112 breweries, was the fifth largest producer of beer in the United States despite ranking only 20th in terms of population.

In 1920 alone, at least 20 of these breweries closed, including the Appleton Brewery and Duluth’s Fitger Brewing Co. Others survived by switching products. The Kiewel Brewery in Little Falls used its former cold beer rooms to churn and keep ice cream and produce non-alcoholic malt beverages. Other breweries took more drastic measures. In 1924, brewery owner Mathew Pitzl of New Munich avoided charges of illegally selling beer by moving his operation to Saskatchewan on a 14-car Soo Line train. No new brewery was built in Minnesota until Summit in 1998.

Saloons, too, were hit hard. Two brothers named Radosevich, who had arrived in the United States in 1900 barely able to speak English, worked down coal mines for six years to build up enough capital to open their European Saloon in Bovey, Minnesota. When Prohibition closed their doors, one of the Radosevich brothers, according to family folklore, turned to smuggling Canadian whiskey.

People still want to drink

Prohibition outlawed the supply of alcohol, but it did nothing about demand.

Many otherwise law abiding people simply didn’t think the law was right. If they wanted to drink, what business was it of anyone else? Eliot Ness, the Prohibition agent famous for bringing down Al Capone, remembered, “Doubts raced through my mind as I considered the feasibility of enforcing a law which the majority of honest citizens didn’t seem to want.” This was especially the case in Minnesota with its large German and Irish populations for whom drinking was deeply ingrained in their culture.

And where there was demand, there was supply. In 1922, St.Paul Acting Police Chief Michael Gebhardt predicted that, “There will be moon as long as the moon shines and people are just beginning to realize how many persons know how to make it.” He estimated that 75 percent of St. Paul residents were distilling moonshine or making wine. “You could buy it if you knew a druggist…They made their own gin and you could buy it in any drugstore,” recalled Nate Bomberg, a crime reporter for the Pioneer Press.

Nearly every farmer in Stearns County began producing a drink known as “Minnesota 13,” named after a variety of seed corn developed by the University of Minnesota. Former club musician Bob Burns, quoted in Paul Maccabee’s book John Dillinger Slept Here, called it “the best moonshine you could buy. They made it clean. Some of the moonshine made up in Minneapolis…it was so rotten that you’d take the cork out and just the smell of it would make you sick.”

There was a high end to this market. According to the Justice Department, Benny Haskell, who sold champagne, scotch, and gin out of the Radisson Hotel in Minneapolis, catered “to a most exclusive clientele of prominent business and professional people in Minneapolis, St. Paul, and Winona.”

Not all saloon owners reacted as Ely’s Radosevich brothers did. Many stayed in business; they just added payoffs to corrupt officials to their operating costs. These“speakeasies,” also known as “blind pigs,” dotted the state. Bessie Green, an associate of John Dillinger’s, ran the Alamo Nightclub in White Bear Lake, which catered to some of the most notorious local gangland figures. Several former speakeasies still exist in some form, such as the 5-8 Club on the corner of Cedar and 58th Street in Minneapolis, Phil’s Tara Hide- away in Stillwater, and the Tavern of Northfield.

Organized crime moves in

Making supply of alcohol illegal despite persistent demand guaranteed high returns, which encouraged criminals to fill the gap once occupied by legal breweries and distilleries.

Bootlegging was a nationwide problem throughout Prohibition, but several factors made the situation in Minnesota more acute. Besides its drink friendly population, St. Paul, a major rail center, was ideally located to act as a hub for the distribution of bootleg alcohol disguised as scrap iron shipments, hair tonic, castor oil, paint, varnish, “printer’s supplies,” and even “saddlery.” Much of this passed through the Midway “Transfer District,” and some of Minnesota’s busiest redistillation factories and speakeasies popped up there. The state’s northern border with Canada, sparsely populated and thickly wooded, was also a popular route for smuggling.

The profits from bootlegging enabled small-timecrooks to become big-time operators. The Minnesota Blueing Company of Leon Gleckman, “St.Paul’s Al Capone,” generated profits in excess of$1 million annually from its dozen or so stills.

Isadore Blumenfeld, known as “Kid Cann,” a petty criminal from Minneapolis’ North Side, established a “perfume factory” called La Pompador that required the use of industrial-grade alcohol imported legally from Canada. The alcohol was then moved to a network of stills in the woods near Fort Snelling where it was turned into “bang-up alky,” 139-proof liquor that sold for $10 a gallon. Cann became a “capo”—someone whohas been officially inducted into the mafia—and a lieutenant forthe notorious gangster Meyer Lansky. He became so powerful that when Hubert Humphrey was elected Mayor of Minneapolis in 1945 promising to clean up the city, he was warned off interfering with Cann’s operations.

These profits were worth killing over. Cann’s group of racketeers called the “Syndicate” split Minneapolis with the “Combination” of Irish mobster Tommy Banks, but disputes were not always so peacefully resolved. On December 4th, 1928, “Dapper” Dan Hogan, a gangster and owner of the Green Lantern Saloon on St. Paul’s Wabasha Street, was killed outside his house on West Seventh Street by one of the world’s first car bombs. The FBI’s prime suspect in the case was Hogan’s underboss Harry Sawyer, known as “Harry Dutch,” who took the Saloon over with suspicious haste.

Cann had a good relationship with the local authorities and killed to keep it quiet. He was suspected of murdering three journalists, most notoriously Walter Liggett, editor of Plain Talk magazine and the Midwest American newspaper. Liggett had been investigating Cann’s ties with the Farmer-Labor Party, particularly Minnesota’s Governor Floyd B. Olson. He had been beaten by Cann’s associates and prosecuted on trumped up charges. On December 9th, 1935, he was machine-gunned to death outside his apartment in full view of his wife and daughter.

Law enforcement gets corrupted

These profits corrupted law enforcement, although admittedly, this didn’t take much effort in St. Paul. There, the longstanding “layover agreement” guaranteed safe harbor for criminals such as Alvin “Creepy” Karpis, John Dillinger, “Ma” Barker, Lester “Baby Face Nelson” Gillis, and George “Machine Gun Kelly” Barnes. All spent time safely in the city, as long as they did not commit crime within the city limits.

Prohibition made this worse. In 1920, northwest Prohibition Chief Paul D. Keller launched an investigation of his entire staff after bootleggers were tipped off to almost every major raid he undertook in Minnesota. In 1926, a local bootlegger told Treasury agents that corruption was so rife in St. Paul that, when his booze was confiscated, a local crook had been able to simply walk into the central police station and walk out with it. Walter Liggett’s wife picked Kid Cann out of a police lineup asher husband’s killer and another three witnesses also identified him as the gunman. Police tracked down the car from which the shots were fired and identified the owner as Meyer Schuldberg, a known associate of Cann’s. Despite this and considerable other evidence, Cann was acquitted.

Law enforcement had an impossible task

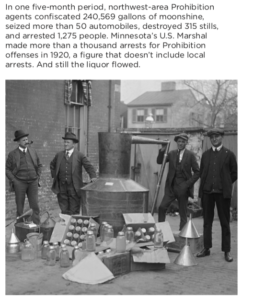

Enforcement of Prohibition was both too lax to stamp out the production and distribution of liquor and oppressive enough to upset the general public.

In one five-month period, northwest-area Prohibition agents confiscated 240,569 gallons of moonshine, seized more than 50 automobiles, destroyed 315 stills, and arrested 1,275 people. Minnesota’s U.S. Marshal made more than a thousand arrests for Prohibition offenses in 1920, a figure that doesn’t include local arrests. And still the liquor flowed.

One evening in May 1929, candy store owner Henry Virkula from Big Falls was driving home after visiting International Falls with his wife and children. According to Time magazine, “Suddenly two figures leaped up before him. One held a sign: STOP! U.S. CUSTOMS OFFICERS. Virkula braked his car but had not stopped before a volley of shot tore through the rear windows. The car plunged into a ditch. Virkula was dead, a slug in his neck. U.S. Border Patrolman Emmet J. White, 24, came up to the car. Shrieked Mrs. Virkula: ‘You’ve killed him.’ Replied White, ‘I’m sorry, lady, but I done my duty.’ No liquor was found. The Virkula children woke up, began to cry.”

Patrolman White had fired five rounds from a sawed-off shotgun into the Virkula car. His defense: the machine did not stop when Patrolman Emil Servine held up the stop sign. White was lodged in jail, charged with murder. The little town’s citizenry seethed with indignation against White and “the system” he represented. Banding together they wrote a public protest to President Hoover which concluded: “In our utter helplessness, terror and distraction, we are at last resorting to you. For God’s sake, help us!”

Such incidents made Prohibition even less popular.

Why did Prohibition fail?

Prohibition failed. But why did it fail? Its supporters argued that the law simply had not been enforced rigorously enough. But most people did not regard the law as legitimate. They could see no reason why the government should prevent them from drinking if they wanted to do so. So, with the aid of bootleggers, they continued to drink. How much more rigorous would enforcement need to have been to ensure compliance with a law most people disagreed with?

In Law, Legislation and Liberty, the economist and philosopher Friedrich von Hayek argued that there was fundamental difference between law—which is that set of rules that emerges “spontaneously,” unplanned and undesigned—and legislation, which is a set of rules and commands that government consciously designs and imposes. We do not refrain from committing murder because it is illegal, but we think that it is wrong, a belief widelyshared among society. The law reflects this belief. Prohibition can be seen as an example of what Hayek would have called legislation. It did not emerge spontaneously from a belief widely held in society, especially not in Minnesota. Rather, it was forced upon them by legislators, responding to a concentrated campaign of lobbying from the Temperance movement, in an attempt to change their behavior. That is why the War on Alcohol failed.

Prohibition was the last great act of the Progressive Era in American politics. The Progressives of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries believed that society could be perfected by the application of enlightened legislation. Where legislation conflicted with widely held social beliefs, those beliefs would change. The failure of Prohibition proved that idea to be false; social beliefs proved resilient to legislation. In modern terms, will a legislative War on Guns succeed where a majority of Americans continue to believe in their right to own them, as their ancestors believed in their right to a drink? Prohibition was also, then, the Progressives’ greatest failure.

John Phelan is an economist with the Center of the American Experiment.