It’s Brexit Day – How did we get here?

Today is Brexit Day in Britain, the day on which, more than three years after voting to leave the European Union, the country actually does so.

In Thinking Minnesota last year, I explained how Britain came to Brexit. To mark Brexit Day, that article is posted below with a short postscript to bring it up to date.

Why Nigel Farage Deserves Your Attention

A brief history of Britain and the EU

There had been schemes to unite the peoples and countries of Europe under a single federal government kicking around for decades. These schemes were given a new impetus by World War II. For the second time in 50 years, Europe had plunged into the biggest war then known and taken much of the rest of the world with it. In the aftermath, it was thought, one way to stop this from happening again would be to put vital war making industries under international control. So, in 1952, Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and West Germany signed the Treaty of Paris, which established the European Coal and Steel Community.

Supporters of federalism pushed on. They drew support from the United States and a shared fear of Sovietdominated Eastern Europe. On top of this, European countries were losing their empires and worried about the impact of this on their economic and political standing. These fears drew the countries’ governments closer and, in 1957, the Treaty of Rome established the European Economic Community (EEC).

Britain wasn’t one of the six signatories; it still saw itself as strong enough to stand on its own as a nation and different enough from its European neighbors to be a bad fit. But by 1961, Britain was feeling less sure of itself and applied to join. Its application was vetoed by French President Charles de Gaulle. De Gaulle similarly vetoed a second application in 1967. A passionate anti-American, he worried that British membership would be a means for the U.S. to control the EEC. He died in 1970, and Britain became a member in 1973, at the third time of asking.

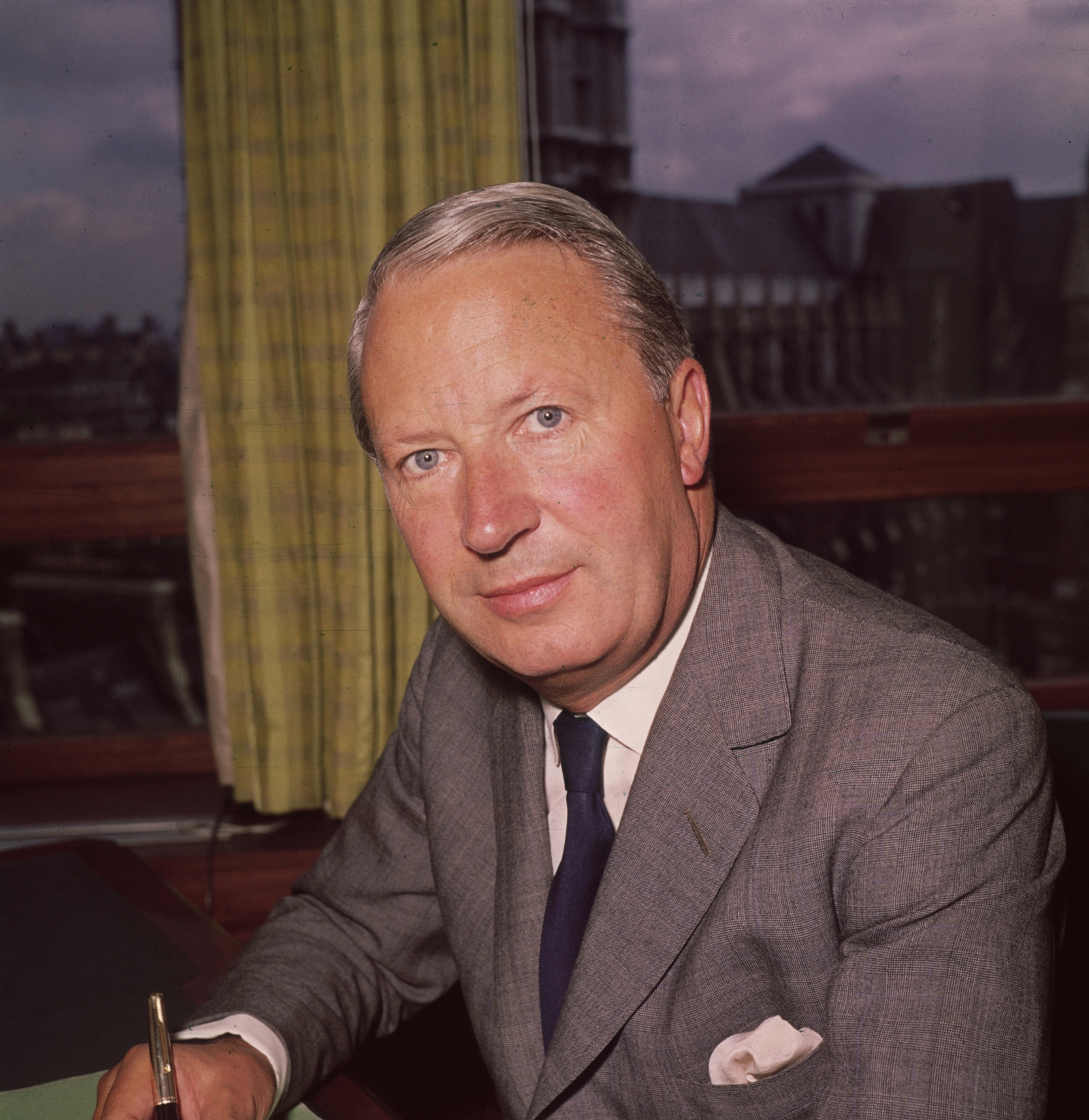

Edward Heath, the Conservative Prime Minister who took Britain into the EEC, said “there are some in this country who fear that in going into Europe we shall in some way sacrifice independence and sovereignty. These fears, I need hardly say, are completely unjustified.” Then, the Labour Party supported withdrawal from the EEC. Elected in 1974, they held a referendum on membership in 1975. Remain won with 67 percent of the vote.

Over the years, Heath’s promise proved to be hollow. The European federalists pushed for still deeper integration. The Maastricht Treaty of 1993 established the European Union—a very different organization from the trading bloc Britain joined. The EU began to take more power from national governments. Fortunately, the UK escaped the worst excess of this push for a United States of Europe—the disastrous single currency—but still found itself ever less sovereign, with the power of the British people residing with unelected bureaucrats in another country.

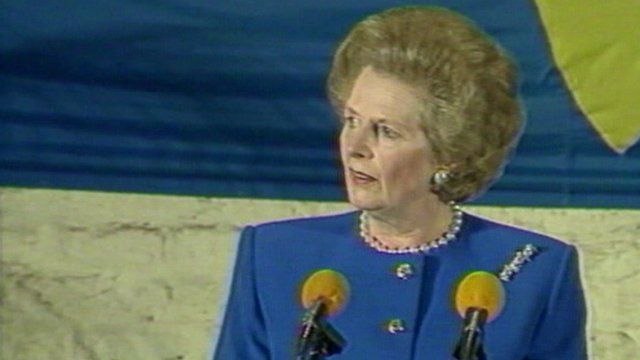

The main parties all supported this. Margaret Thatcher’s successor as Prime Minister, John Major, rammed Maastricht through the House of Commons despite the bitter opposition of a large part of his own party. Conservative Party membership cratered and has never recovered. The Labour Party saw the increasingly friendly attitude of the EU to regulation and increased taxation, and ditched its old policy of withdrawal. The Liberal Democrats, eager for any issue to be distinctive on, were the most federalist party of all. Bizarrely, Britain’s nationalist parties, the SNP in Scotland and Plaid Cymru in Wales, also supported increased control of their countries by European bureaucrats.

The rise of UKIP and Nigel Farage

There was a demand for a party dedicated to getting Britain out of the EU, and the political market supplied it. The United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) was founded in 1993. It quickly became a home for disaffected Conservatives but struggled to make much impact, as Tony Blair’s Labour Party swept the Conservatives from office in 1997.

British discontent with the EU continued to grow as more power shifted away from the British government. In the 2004 European Parliament elections, UKIP came third with 12 members of the European Parliament (MEPs) elected. In 2006, Nigel Farage became UKIP’s leader. He sought to broaden the party’s appeal beyond the single issue of EU membership. The Conservatives had just elected David Cameron as leader, and he called himself the “Heir to Blair.” He copied Blair’s liberal, metropolitan world view and fatuous style. He went to the North Pole to ride a sled in front of TV cameras to make some point about climate change. In response to rising crime, he urged the public to “Hug a hoodie.” Unsurprisingly, this had little appeal to most conservatives. Farage spotted a gap in the market for a small “c” conservative party which would reduce taxes and spending, be tougher on law and order, and try to get control of immigration as Britain’s population surged. Cameron described these people as “fruitcakes, loonies and closet racists, mostly.” But voters responded. While UKIP continued to struggle in domestic elections, in the 2009 European elections, ironically, the party came second with 16.5 percent of the vote and 13 MEPs.

Between 2005 and 2010, Cameron’s strategy was that if he annoyed the Conservative right enough, he would attract enough “center” ground votes to more than compensate. This strategy failed. At the 2010 general election, amid the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression and against one of the worst Prime Ministers in British history, the Conservatives failed to win. They only entered government in coalition with the Liberal Democrats. In the election, UKIP polled 3.1 percent of the vote (919,471 votes), an increase of 0.9 percent on the 2005 general election. In the 2014 European Parliament elections, UKIP received the greatest number of votes (27.49 percent) of any British party and gained 11 extra MEPs for a total of 24. UKIP won seats in every region of Great Britain, including its first in Scotland. It was the first time in over a century that a party other than Labour or Conservatives won the most votes in a UK-wide election.

Thanks to the rise in UKIP’s popularity, in large part a result of Farage’s leadership, the Conservative Party came to wonder how it could ever win another election. The idea developed that they needed to “shoot UKIP’s fox” by holding a referendum on EU membership. In the general election of 2015, the Conservatives ran on a manifesto promising such a referendum. To the surprise of most, they won. Committed to a referendum, it was held in 2016.

The rest is not yet history. Britain was due to leave the EU at the end of March. This has been delayed. EU federalists in the UK continue to try to ignore or overturn the result of the 2016 referendum. They may yet succeed.

But that result will not go away. It will remain a British declaration of independence. And the role of our Annual Dinner speaker, Nigel Farage, in securing that, was vital.

Postscript – From Independence Day to Brexit Day

The day after the referendum, David Cameron resigned as Prime Minister, reportedly saying

“Why should I do all the hard s**t for someone else, just to hand it over to them on a plate?”

This attitude that would have been anathema to previous Conservative leaders such as Thatcher and Winston Churchill.

Boris Johnson, the high profile former Mayor of London turned Conservative MP, had been a leading campaigner for Brexit and ran to replace Cameron, but his campaign was derailed when another prominent Leaver, Michael Gove, announced that he couldn’t support him. The Conservatives – as so often – ended up picking the candidate least offensive to everyone, Theresa May, who had campaigned, albeit unenthusiastically, to Remain.

On March 29th, 2017, May triggered Article 50, the process governing how an EU member nation leaves. It states:

The Treaties shall cease to apply to the State in question from the date of entry into force of the withdrawal agreement or, failing that, two years after the notification referred to in paragraph 2, unless the European Council, in agreement with the Member State concerned, unanimously decides to extend this period.

Brexit Day was set for, at the latest, March 29th, 2019.

Then, on April 8th, 2017, May called a general election for June 8th. With the Conservatives riding high in the polls, she sought to expand her majority in the House of Commons to push through whatever withdrawal agreement she negotiated with the EU. It turned out to be a disastrous blunder. The campaign was long by British standards and May hid herself away, banking on the unpopularity of Labour’s Jeremy Corbyn to propel her to victory. Instead, while the Conservative vote surged from 2015’s tally by 5.5 percentage points to 42.3%, their highest share since Thatcher’s second victory in 1983, Labour’s vote rose by 9.6 percentage points to 40.0%, their best showing since Tony Blair’s second victory in 2001. The Conservatives remained the biggest party in Parliament but lost their majority, and had to enter into a demeaning deal with Northern Ireland’s Democratic Unionist Party.

In July 2018, May finalized a proposed future relationship between Britain and the EU, known as the Chequers agreement. Believing that it let the EU retain too much control, Leave supporting ministers resigned in protest, including Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson. In September, May was humiliated when the EU refused the deal anyway. In November, a new Brexit withdrawal agreement was published, prompting further resignations. In December, May survived an attempt by Conservative MPs to replace her. The other EU members endorsed this deal, but Parliament voted against in January, 2019. In March, with Brexit Day only two weeks away, Parliament rejected it again. Despite the wording of Article 50 – “The Treaties shall cease to apply to the State in question from the date of entry into force of the withdrawal agreement or, failing that, two years after the notification” [emphasis added] – the government sought and got an extension. The European Council offered to extend the Article 50 period until 22nd May if the Withdrawal Agreement was passed by 29th March but, if not, then the UK had until 12th April 2019 to indicate a way forward.

The British political situation was now impossible. The people had voted to Leave the EU, but the majority in Parliament had always supported Remaining. In the 2017 general election, both Conservative and Labour candidates ran on platforms of respecting the referendum. It now turned out that many of them hadn’t meant this. Once back in Westminster, they set their faces to blocking both any deal and leaving with no deal, the de facto result being that Britain would remain in the EU.

So, on March 29th, May’s deal was rejected by Parliament for a third time. Rather than leaving without a deal as per Article 50, May requested a further extension to June 30th, but without any clear idea of what she would do with this extra time. The EU gave her an extension to October 31st, the new Brexit Day.

On May 23rd, Nigel Farage’s new Brexit Party – he had stepped down from Ukip after the referendum – won 29 seats in the European Parliamentary elections. The Conservative vote share slumped by 14.3 percentage points and they lost 15 of the 19 seats they had won in 2014. This was a grim foretaste of what awaited the Party if it didn’t get Brexit done. The following day, Theresa May announced that she would resign as Party leader, effective 7th June.

She was replaced by Boris Johnson, who now had broad support in the party including that of Michael Gove. On July 25th, a day after Johnson became Prime Minister, Parliament went into summer recess until 3rd September. On August 28th, Johnson announced his intention to prorogue Parliament. This process essentially ends one parliament before opening another with a Queen’s Speech scheduled, in this case, for October 14th. Remainers cried foul because this would leave just two weeks to pass legislation to avoid a No Deal Brexit, despite that being the default position of the legislation Parliament itself had voted for when it triggered Article 50.

Remainers in Parliament began attempting to legislate to prevent the UK leaving the EU without a withdrawal agreement, something Johnson rightly claimed tied his hands in negotiations. To break the impasse, Johnson twice attempted to call a general election for October. But, in a quite unprecedented move, the Labour Party opposed this, rejecting the chance to replace the government. On September 24th, the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom ruled Johnson’s decision to advise the Queen to prorogue parliament was unlawful, and that the prorogation itself therefore null and of no effect. Parliament was recalled the following day.

But the problem facing Remianers was now the same as that which had faced Theresa May: they returned to Parliament without any firm idea what to do once they got there. Some, such as the Liberal Democrats (sic), wanted to simply cancel the result of the referendum and revoke Article 50. Most wanted a second vote – misleadingly labelled a ‘People’s Vote’ – but few were brave or brazen enough to push this position openly. Mostly, they dithered, clinging to the strategy of delay and Remain de facto. From this point on, Johnson held the initiative.

On October 2nd, Johnson announced his proposed withdrawal agreement and won wide support for it in the Conservative Party. On October 17th, the EU agreed to it. But, even with this in place, Parliament voted for a further delay on October 19th. There was no conceivable reason for this and the strategy of delay and Remain de facto was ruthlessly exposed. This fresh delay pushed the date back past October 31st – Brexit Day – and meant that Johnson now had to send a letter to the European Council with a request for an extension of withdrawal until 31 January 2020. Johnson sent this letter, as he was legally required to, but also sent a second saying the delay was pointless, which it clearly was.

Johnson continued to call for a general election and Parliament continued to refuse. It was becoming increasingly clear that the House of Commons, far from being the voice of the people, was actively trying to block the implementation of what the people had voted for and deny them the opportunity to elect others who would. The Labour Party looked especially cynical. With the need to reconcile their Leave voting northern industrial heartlands and their Remain voting, urban middle class membership, they opted for no policy at all. Realizing how gutless this was, the leadership ran as fast and far as it could from the electorate, repeatedly blocking Johnson’s request for a general election.

On October 22nd, Johnson’s withdrawal agreement passed on its first reading. On October 28th, the European Council agreed to a third extension: Brexit Day would now be January 31st, 2020. The same day, a fresh attempt by Johnson to call a general election rejected by Parliament. In a bold move the following day, he pulled the withdrawal agreement and introduced the Early Parliamentary General Election Act 2019. This legislated for a general election to be held on December 12th. With nowhere left to hide, Labour had no choice but to agree.

The general election was an historic success for Johnson and the Conservatives. Their vote edged up by only 1.3 percentage points from 2017, but Labour’s collapsed, by 7.8 percentage points to 32.2%, their worst showing since Thatcher’s third victory in 1987. In terms of seats, Labour won just 202, down 60, for their worst performance since 1935. Their cowardice over Brexit saw them lose votes in their northern, Leave voting heartlands to both the Brexit Party and, incredibly, the Conservatives, and to the Liberal Democrats in Remain supporting urban areas. The Conservatives won a hefty majority of 80, their largest since 1987. Johnson was now able to deliver on his election slogan and Get Brexit Done.

John Phelan is an economist at the Center of the American Experiment.