Literature on childcare says strict regulation=higher prices

Minnesota is one of the most expensive states for childcare. And not only that, but childcare is also hard to access due to a shortage of spaces. The coronavirus has made this crisis worse. And to solve this crisis, Minnesota should look into deregulating the childcare industry. The literature on childcare regulation agrees with this sentiment. Evidence presented by most research shows that strict regulation significantly raises the cost of childcare.

Regulation and the cost of childcare

One of the most recent studies on the regulation of childcare is a study by Diana Thomas and Devon Gory. Authors from this study found evidence suggesting that “regulations intended to improve the quality of child care often focus on easily observable measures, such as group sizes or child–staff ratios, that do not necessarily affect the quality of care but do increase the cost of care.”

Generally, the quality of childcare is measured by looking at two things (1) structural measures and (2) process measures. Structural measures involve easily observable characteristics like child-to-staff ratio, group sizes, teacher education requirements, and program administration. Process measures, however, are hard to observe and focus on the quality of interactions between a teacher and kids.

Licensing bodies usually focus on structural measures to ascertain the level of quality of childcare. However, structural measures are not closely associated with quality; process measures are. Structural measures are heavily focused on because they are easy to observe and measure. But by focusing on these structural measures regulating bodies subject providers to restrictions that limit supply, raise costs, and therefore lead to higher costs of childcare services.

In fact, estimations from the study suggest that loosening some of these restrictions would lead to lower prices in childcare.

Increasing the child–staff ratio by allowing more children per teacher reduces child care costs across all models tested. For example, an increase in the child–staff ratio requirement for infants by one infant is associated with a decrease in the cost of child care of between 9 and 20 percent across all models, which would reduce the annual cost of child care by between $850 and $1,890 per child across all states, on average.

Other studies

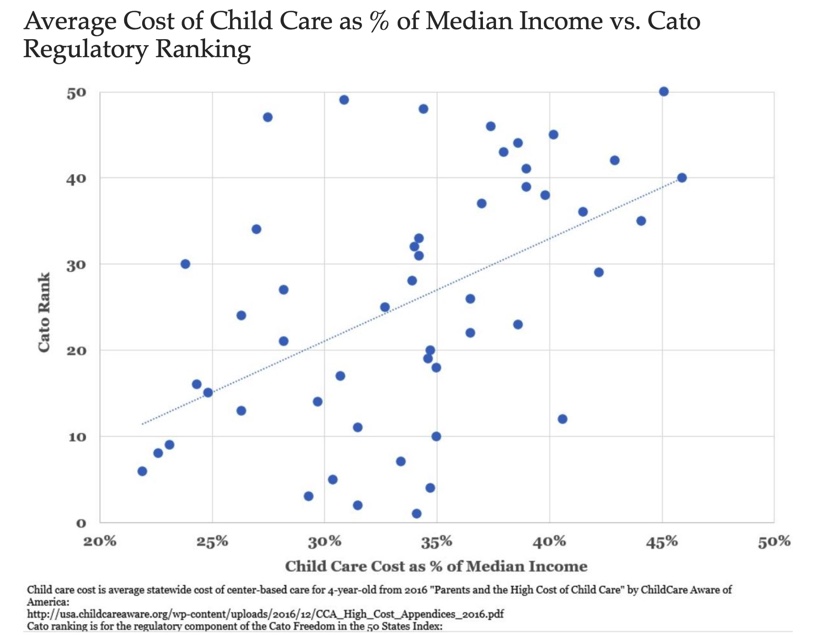

Other studies do have evidence that shows similar results. For instance, a study published by the American Institute for Economic Research (AIER) found that states that ranked as having much stricter regulation using Cato`s Regulatory Ranking have a higher cost of childcare services compared to those that ranked as having less strict regulation.

Randal Heeb and Rebecca Kilburn (2004) also found evidence showing strict childcare ratios raise the price of care at centers and drive other parents to unregulated lower-quality care. In some instances, high prices are responsible for keeping mothers out of the workforce completely. Other studies have found detrimental impacts of strict regulation on other aspects of childcare like supply (Joseph Hotz and Mo Xiao 2011) and workers’ wages (David Blau (2007).

Conclusion

Proponents of strict childcare regulation in Minnesota usually regard current strict standards as responsible for high-quality childcare. However, evidence shows that this is not factual. Most measures that the Minnesota Department of Services uses to analyze quality like child-staff ratios and group sizes have no discernible effect on quality. Instead, they only work to raise prices for parents and make it harder for providers to make profits.