Minnesota’s 2021 minimum wage hike: bad policy coinciding with very bad timing

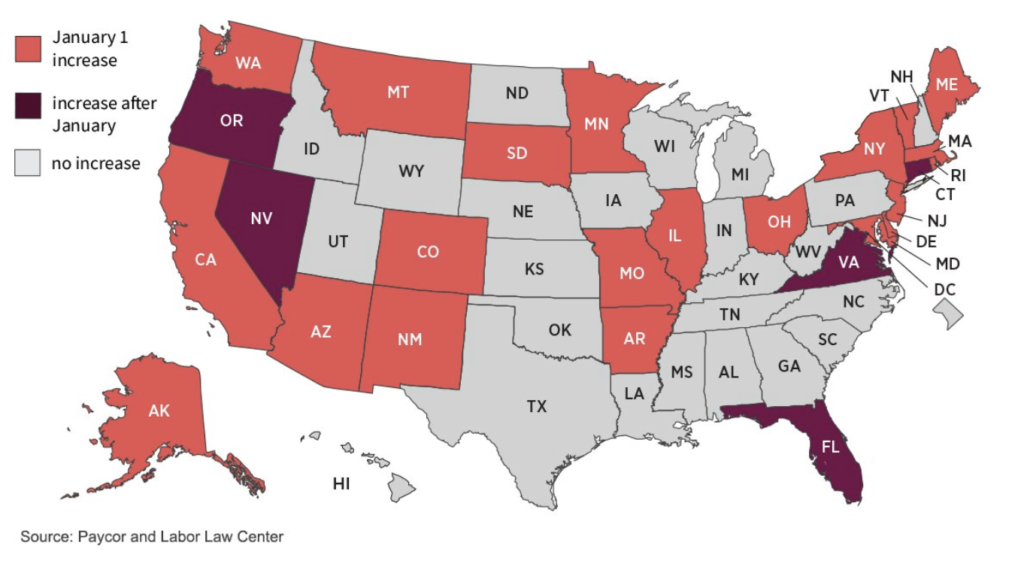

The beginning of the new year has come with it some new changes. For example, 25 states, including Minnesota, have raised their minimum wage beginning January 1st, 2021. More than half of these states are raising their wages to $15 or more. Minnesota’s minimum wage raise is one of the lowest among the states, only going up by $.08 for big employers and $.06 for small employers. However, other raises are scheduled later during the year for the twin cities.

Raising the minimum wage is generally a bad policy

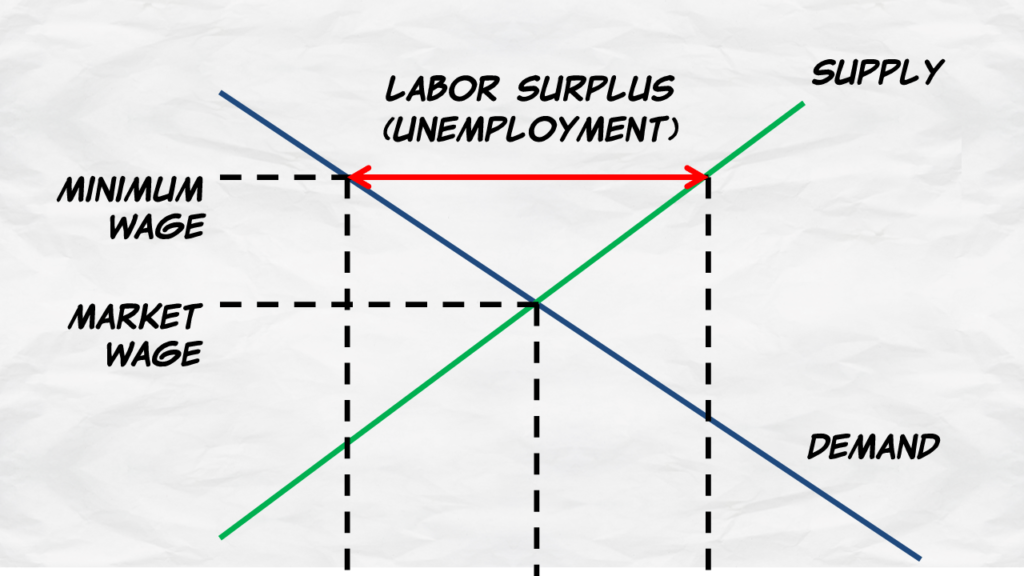

Generally, price ceilings or floor are bad economic policy as they disincentivize productive economic activity. When it comes to the minimum wage, this is especially true for low-skilled and young workers that are denied jobs when the minimum wage goes up. Additionally, a high minimum wage also disadvantages other groups like disabled workers and minority workers.

As shown in the graph below, the minimum wage works like a price floor. So, this means employers cannot legally hire any person at a price below the mandated wage, even if it is remarkably above the market wage. What this entails is that labor demand will decrease. This effect is more pronounced for low skill, low productive jobs that are often taken up by low income, low educated, and young workers forcing them out of the job market.

Source: Marginal Revolution University

One issue that especially makes one size fits all minimum wage policy harmful is differences in living costs. In Minnesota, for instance, living costs in the twin cities are significantly higher than those of greater Minnesota. This makes it necessary to have wage differentials. Mandating the same minimum wage statewide disproportionately hurts workers and businesses in comparatively low-income regions. Not to say minimum wage hikes are appropriate for higher-income areas, but it is important to recognize these differences.

This is especially bad timing

The economy is struggling, and small businesses are in an especially dire predicament. So, this is an especially bad time to raise the minimum wage, especially considering the fact that most minimum wage workers are in industries that have been heavily affected during the coronavirus crisis.

While one might argue that Minnesota’s raise is no a significant change, these costs add up. And to most small businesses that have suffered greatly from the lockdowns, cumulatively higher labor costs are a significant burden to operating efficiently.

Furthermore, policymakers need to understand that how policy affects decisions at the margin is very important. While on average businesses would be able to swallow the increased costs of paying more, they would be incentivized to change their decisions in the future. Take for instance the decision whether or not to hire one more worker. If the minimum wage is too high, businesses would be deterred from expanding or hiring more workers in the future. And the opposite is true where there is no minimum wage law or the limit is low.

As we already know, the minimum-wage workforce is made up of young, low-skilled workers, who are less likely to be married. This makes raising the minimum wage an ineffective tool to reduce household poverty. Additionally, research has shown wages have grown significantly not due to minimum wage laws. Growth in wages has instead followed growth in income and production. Therefore, raising the minimum wage, especially at a time when small businesses are hurting is just a sure recipe for disaster.