There are lots of jobs in wind energy…just not much energy

Another day, another puff piece about renewable energy.

Lobby group Clean Energy Economy Minnesota has released a study extolling the virtues of wind energy. Oddly, it doesn’t do so on the basis of the energy produced. It does it on the number of people it takes to produce it. As the Star Tribune breathlessly reports,

As wind and solar energy have grown, they’ve created a tide of jobs nationwide in fields from construction to manufacturing. Renewable energy jobs, most of which are in wind and solar, grew by 16 percent to around 6,200 in Minnesota from 2015 to 2016, according to a recent study by Clean Energy Economy Minnesota, an industry-led nonprofit.

…

The U.S. Energy Department’s 2017 report concluded that solar generation employed 373,807 people nationwide — the most of any type of electric power production. Wind was second with 101,738 workers; coal generation was third with 86,035, not including 74,000 coal miners.

Its outputs, not inputs that matter

Something about this should strike you as a bit off.

As I’ve written recently, what matters for economic growth is productivity. This means getting more output out of the same amount of inputs. More output per head is how we get better off. In other words, the point is to grow output, not inputs.

So, when we see that wind power employs so many people, that is not necessarily a good sign. These are inputs and it is outputs that count. And when we look at the ratio of inputs to outputs, wind power fares very, very badly indeed. As the Washington Examiner reported in May,

To start, despite a huge workforce of almost 400,000 solar workers (about 20 percent of electric power payrolls in 2016), that sector produced an insignificant share, less than 1 percent, of the electric power generated in the United States last year (EIA data here). And that’s a lot of solar workers: about the same as the combined number of employees working at Exxon Mobil, Chevron, Apple, Johnson & Johnson, Microsoft, Pfizer, Ford Motor Company and Procter & Gamble.

In contrast, it took about the same number of natural gas workers (398,235) last year to produce more than one-third of U.S. electric power, or 37 times more electricity than solar’s minuscule share of 0.90 percent. And with only 160,000 coal workers (less than half the number of workers in either solar or gas), that sector produced nearly one-third (almost as much as gas) of U.S. electricity last year.

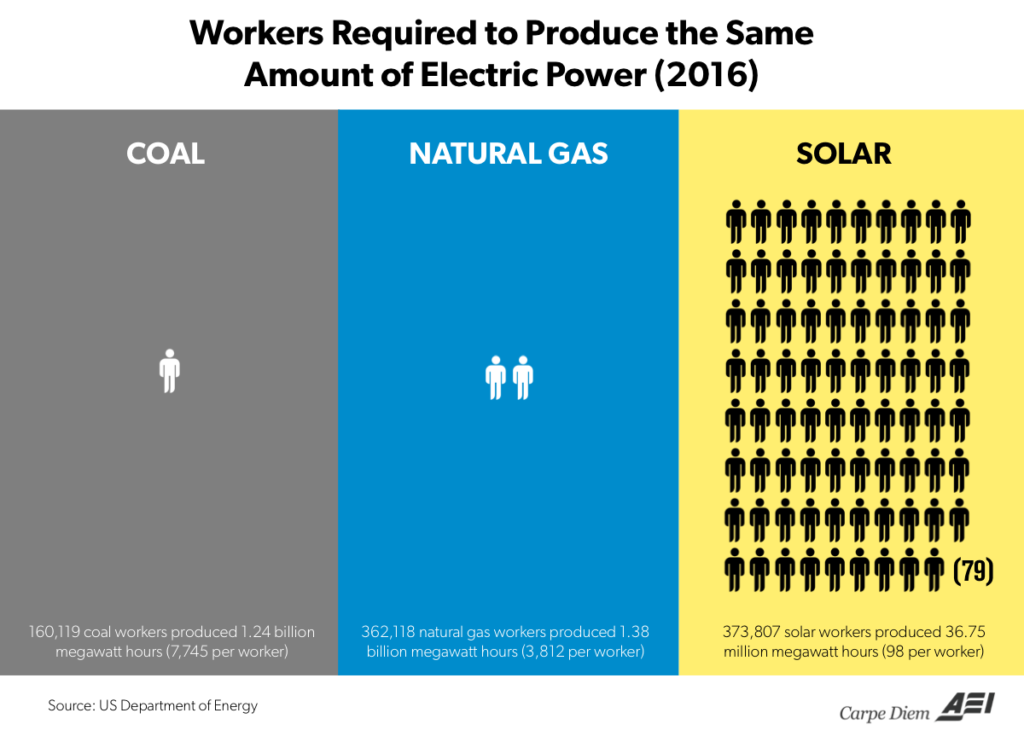

The graphic above helps to quantify the significant differences in electric power output per employee for coal, natural gas and solar workers. In 2016, the coal sector generated an average of 7,745 megawatt hours of electric power per worker, more than twice the 3,812 megawatt hours of electricity generated per natural gas worker, and 79 times more electric power per worker than the solar industry, which produced only 98 megawatt hours of electricity per worker. Therefore, to produce the same amount of electric power as just one coal worker would require two natural gas workers and an amazingly-high 79 solar workers.

Get blowing

Stephen Moore tells the following story about Milton Friedman

At one of our dinners, Milton recalled traveling to an Asian country in the 1960s and visiting a worksite where a new canal was being built. He was shocked to see that, instead of modern tractors and earth movers, the workers had shovels. He asked why there were so few machines. The government bureaucrat explained: “You don’t understand. This is a jobs program.” To which Milton replied: “Oh, I thought you were trying to build a canal. If it’s jobs you want, then you should give these workers spoons, not shovels.”

The point of an energy industry is to generate energy, not to generate jobs. If it was, we could hire people to stand in front of wind turbines blowing at them to make them turn faster. The effect energy generation would be non existent but the effect on employment need only be limited by how many blowers we can fit in a field.

There’s more on energy policy in Minnesota and the costs to the state’s residents in our new report, Energy Policy in Minnesota: the High Cost of Failure.

John Phelan is an economist at the Center of the American Experiment.