Youth unemployment worldwide: The canary in the coal mine of excessive regulation

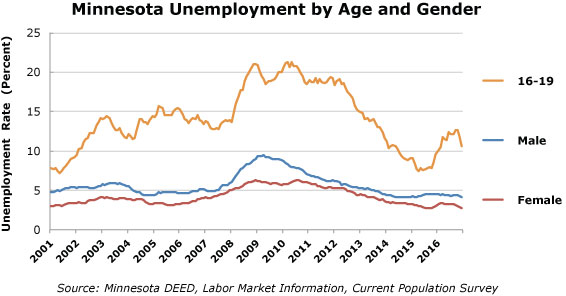

Amid good recent news on Minnesota’s labor market, one troubling spot has been youth unemployment. According to the Department for Employment and Economic Development, 9.6% of 16-19 year olds were unemployed in Minnesota in November 2016. In November 2017, that was up to 10.6%.

DEED observe that “Recent increases in teen unemployment coincides with an increase in the state minimum wage to $9.50 per hour ($7.75 for those under 18) in August 2016, which is notable because minimum wage rules tend to apply disproportionately to teen workers.”

In a new paper titled Youth Unemployment Worldwide: The Canary in the Coal Mine of Excessive Regulation, the economist Deirdre McCloskey looks at the causes and consequences of youth unemployment on a global basis.

The central responsibility of an academic economist is to give the bad news that such and such a policy beloved of politicians and journalists is bad. Arnold Harberger is fond of pointing out that the salaries of all the academic economists worldwide could be covered many times over by the economic gain from their repeated bad news that protectionism is bad. I want to tell you today, whether you like it or not, that protecting jobs with regulations and minimums and imposed conditions is bad, and especially bad for our children and grandchildren when they enter, or try to enter, the labor force. It’s a crisis of democracy.

You know the proverbial expression. A caged little bird was brought into coal mines as an early signal for bad air, such as a buildup of carbon monoxide. If the bird died, the miners fled.

You also know that it’s crucial to socialize young men in the puberty rite of responsible jobs. Elephants and lions sidestep the task violently, expelling young males as chronic disturbers of the peace, or revolutionaries. We do it violently, too, occupying the West Side of Chicago. When the late political scientist James Q. Wilson was asked what would prevent crime he would say in jest, “Put all the males in a concentration camp from age 15 to 30.” It’s not that young men are the only criminals or revolutionaries on the scene. Their leaders are of course older. Lenin was 47 in 1917, Mussolini 39 in 1922, Hitler 44 in 1933—though for good or ill, Martin Luther was only 34 in 1517 and Al Capone only 27 in 1926. But as the longshoreman and sage Eric Hoffer noted in his 1951 book The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements, the youths are the cadres, the followers, the storm troopers. No cadres, no revolutions. For good or ill.

I do not mean to suggest that the main reason we should worry about the size and causes of youth unemployment is their violent threat to us oldsters. The main reason we should worry is that a life without employment is a sorry life, whether the youth is a laborer or a university graduate. They are all of them our children and grandchildren, and it would be appalling not to care. Yet the political threat is there, and is a bomb waiting to go off worldwide. Populism in Hungary, socialism in Venezuela. The high rate of youth unemployment in many places nowadays, and its increase since earlier times, signals bad economic air.

One quarter of French young people age 16 to 25, male or female, not in educational programs, are unemployed. The office of the Secretary General’s Envoy on Youth of the United Nations declared in 2016 that “Global Youth Unemployment is on the Rise Again.” Referring to the International Labor Organization’s 2015 report, it says that “the global number of unemployed youth is set to rise by half a million this year to reach 71 million—the first such increase in 3 years.” It is 71 million revolutionary cadres, a mere one percent of the world’s population, true, but a highly volatile part, and anyway 71 million lives blighted. The ILO report says the status of young people “neither employed, nor in education or training (NEET)…carries risks of skills deterioration, underemployment and discouragement. Survey evidence for some 28 countries around the globe shows that roughly 25 per cent of the youth population aged between 15 and 29 years old are categorized as NEET. … [The] rates for youth above the age of 20 years old are consistently higher, and by a wide margin, than those for youth aged 15–19.” [ILO 2015, p. viii; their source is one well-named Elder 2015]. “In South Africa, more than half of all active youth are expected to remain unemployed in 2016, representing the highest youth unemployment rate in the [sub-Saharan] region.” (ILO, p. 5). “Southern European countries are those which report the highest NEET rates [for 25-29 year olds], peaking at 41 per cent in Greece. However, relatively high NEET rates for youth aged 25–29 are also found in the United Kingdom (17 per cent), United States (19.8 per cent), Poland (21.6 per cent) and France (22.5 per cent)” (ILO, p.18). Among 25 OECD countries the five with the highest unemployment rates of 20–29 year olds [roughly 25% to 40% unemployed] are in descending order Greece, Turkey, Italy, Spain, and Morocco. The five with the lowest [roughly 12%] are in descending order Denmark, Austria, Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden (ILO, p. 18, Fig. 5). For a somewhat larger group of 37 countries in 2016 mostly in the OECD (that is, well-off countries by international standards) the rates for 15–24 year olds ranged from Japan’s 5.2% and Iceland’s 6.5% to South Africa’s 53.3% and Greece’s 47.4% of people searching for work and not finding it. Spain’s is 44.5%, Italy’s 37.8%, Portugal’s 27.9%, France’s 24.6% (OECD 2018).

For some reason, undeniably, the actual and potential businesses in such places do not want to hire young men. One explanation commonly put forward is that the schools have failed to make the young men worth hiring. A version of the education explanation, given credence for instance by low rates of youth unemployment in Germany at present, is an absence of apprenticeships and other training for the trades. Yet earlier systems, which did not educate or apprentice young men at all, did not result in disproportionate unemployment.

The ILO attributes the problem to insufficient aggregate demand. Certainly demand is the problem, but the great variation across countries suggests that the problem is more microeconomic. The Great Recession cannot go on explaining why young people stand on street corners seven times more frequently in Greece than in Iceland.

A few years ago I and some others gave talks favoring market liberalism in a hotel in Thessaloniki, northern Greece. We expected 300 people to show up, but 1,000 did, overwhelmingly young people. We had to split the sessions between the top-floor ballroom and a basement area, and run tag-teams of speakers through both venues. The young people were looking for answers to their plight. It was heartbreaking. And, being unemployed anyway, the young men and women of Thessaloniki could just as easily attend next week’s similar introductory meeting of the Communist Party or the neo-fascist Golden Dawn, and doubtless did.

Why, then, do businesspeople not want to hire young people? If one has a job-slot theory of employment, the answer could be a mismatch of skills. One hears a good deal these days about how automation or artificial intelligence will cause mass unemployment. Yet one would suppose that young, flexible workers, who unlike their elders already are a little computer savvy, would be just the ticket. They are not, at any rate not in France and Greece and South Africa.

And the job-slot theory is mistaken. The economy adjusts, if the polity permits it, to the mix of skills available. Job slots in a market economy are not rigid, and cannot be projected, which is to say that they are the outcome of voluntary wage bargains, not given slots at all. They depend on shifting and unpredictable technologies and tastes. If self-driving vehicles surprise us in the next decade, what will happen to projections of job slots for bus and truck drivers? In 2000 video stores employed 130,000 Americans. Now, none. Every year in the U.S. economy, and in any economy in which jobs are not closely regulated by slot planners, or not restricted by law or by unions or political power, 14% of jobs vanish forever. (And in a good year 16% new ones are devised and agreed to.) In 1800 four out of five workers were farmers, and still one third in 1900. Now one out of fifty are, with 200 times more food and fiber produced per worker.

Another theory of employment was once called the wages fund theory. The bosses have a pile of capital expendable on wages. Bargaining power determines how much the workers get. It’s zero sum. Join the picket line or join the party to extract more of the fruits of labor for the laborers. Something like the wages fund theory lies behind the notion that bosses can be squeezed and squeezed with more and more interventions in the wage bargain, more paid vacation time, better working conditions, more job security, without consequences in lower employment. It is the theory behind the denial by some economists and by many more politicians that, say, a higher minimum wage will not result in lower employment. It is an experiment that in 2018 were are performing in many cities and states.

The correct theory of employment is the one devised by the neoclassical economists of the late 19th century, such as Menger and Marshall and Wicksell, and brought to modern form by John R. Hicks in The Theory of Wages (1932). It says that a voluntary deal to hire someone depends on the someone making enough for the employer to be worth the additional hire at the going wage. And the going wage is determined by economy-wide supply of and demand for labor, unless the polity or a monopoly supported by the polity intervenes. The theory is the merest common sense, though fiercely denied in favor of slots or wages funds even by some economists.

What of it? This: if the law or unions or whatever intervenes in the wage bargain, the quantity supplied of labor can exceed the quantity demanded. It’s called unemployment. The case is identical to that of, say, rent control, with supply and demand reversed. Or the wage controls in the United States during World War II that eventuated in the bizarre U.S system of attaching health insurance to one’s present employment.

Why then youth unemployment? In a nutshell, job security for oldsters. Take for example the German labor law of 1994, since relaxed in Germany, that was adopted by South Africa at the coming, thank God, of democracy. In South Africa it is nearly impossible to dismiss a worker once she is hired. The first day I visited South Africa, in 2004, I left a not-very valuable satchel in the restaurant we had just eaten at. Three minutes from the restaurant I said to my host, “Oh, I left a satchel at the place. It’s not got anything valuable in it, and itself is cheap, but can we turn around?” To my astonishment he replied, “It’s fruitless. It’s already been stolen.” He explained that because of the labor law, restaurant workers routinely seize with impunity anything the customers leave, and keep it. Likewise, if the workers steal money from the till, or don’t show up for work, they can be dismissed only if convicted in a court of law. Would you hire anyone, much less a young, untried person, under such circumstances? The Hicksian theory of wages says no. The result is 53% youth unemployment, and no stellar performance for employment at any age.

The minimum wage, too, is high in South Africa. The Congress of South African Trade Unions insists on it. COSATU had an honorable role in the struggle against apartheid, and is viewed with indulgence by politicians. The result is that low-wage workers cannot compete with trade unionists. The poor sit in huts in the countryside of Kwa-Zulu Natal, pacified by a small income subsidy to someone in the family. Low-skilled people, such as young people, don’t have a chance.

In France the extravagant job protections for people who already have jobs means that oldsters cling desperately to the wrong job and youngsters haven’t got a shot at permanent employment. On the West Side of Chicago the war on drugs combined with the minimum wage combined with protective regulations of businesses combined with licensing requirements for 1,000 occupations nationwide combined with zoning preventing opening of businesses large and small combined with building codes in favor of union plumbers and electricians make for no jobs for young people, and frozen jobs for old people.

In other words, high youth unemployment is a signal, a strong one, a canary in the coal mine. It indicates that the polity has intervened too vigorously in the wage bargain and associated conditions of employment.

The West Side of Chicago should be a hive of commercial activity. A century ago, before the interventions took hold, it was.