It wasn’t luck that made Ireland’s Celtic Tiger roar

Ireland, from poorest of the rich to the Celtic Tiger

In 1988, The Economist magazine ran an article on Ireland titled ‘The poorest of the rich’. The title was well deserved.

That year, Irish per capita GDP stood at $11,063, just 70 percent of the figure for the United Kingdom and 52 percent that of the United States. The unemployment rate was 16.2 percent, compared to 8.5 percent in Britain and 5.5 percent in the United States. Irish government debt amounted to 85 percent of GDP compared to 60 percent in the United States and 37 percent in the United Kingdom.

But, when The Economist next came to write about Ireland’s economy in 1997, they called it ‘The Celtic Tiger: Europe’s shining light’.

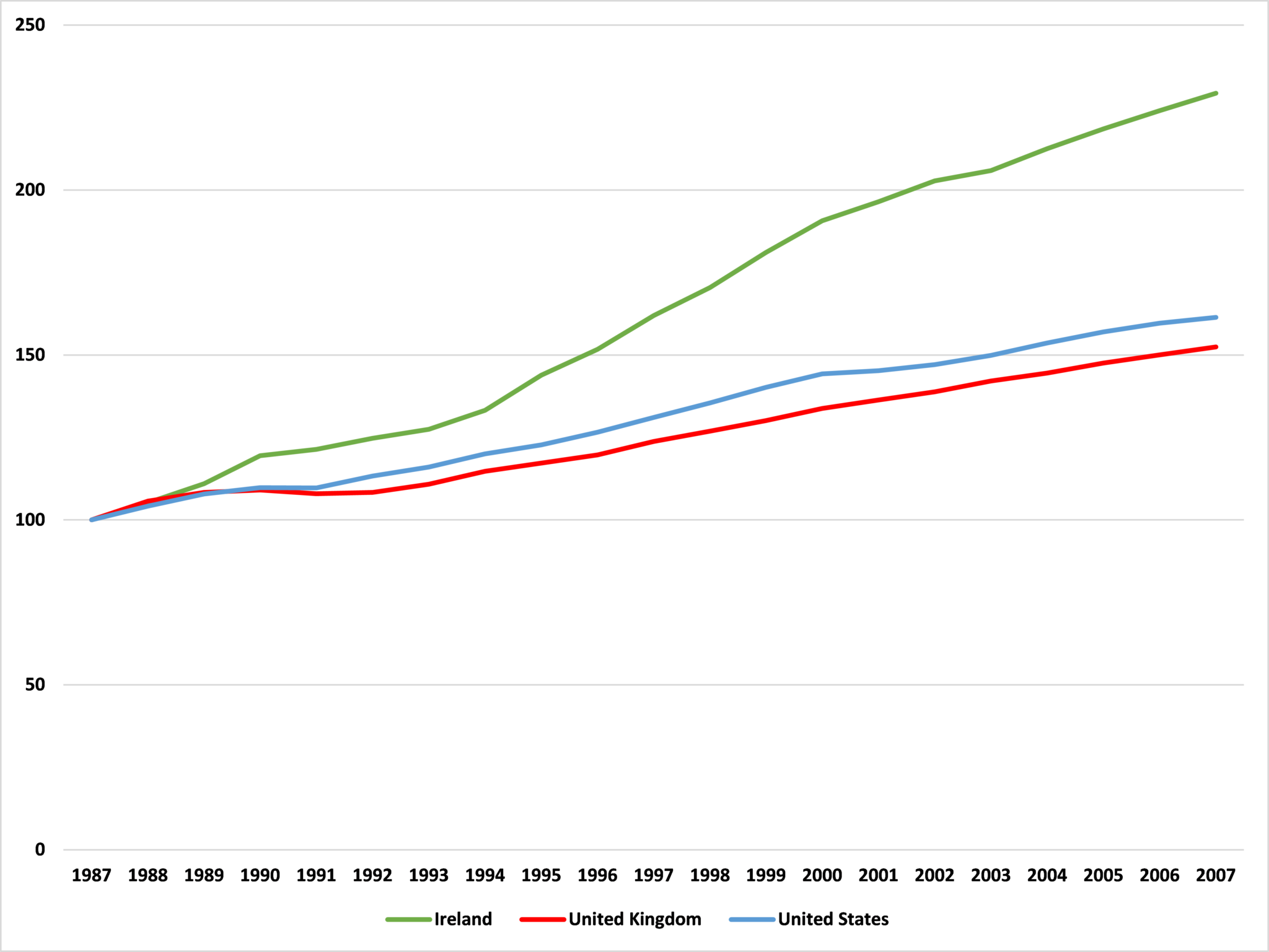

This dramatic turnaround can be seen in the charts below. The Irish economy grew at an average annual rate of 9.4 percent between 1995 and 2000. Real GDP growth outpaced that in the United Kingdom in every year from 1989 to 2003 and that of the United States in every year after 1993. As shown in Figure 1, while Ireland’s GDP grew by 229 percent between 1987 and 2007, in the United States the figure was 161 percent and in the United Kingdom it was 152 percent.

Figure 1 – Real GDP growth, 1987=100

Source: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

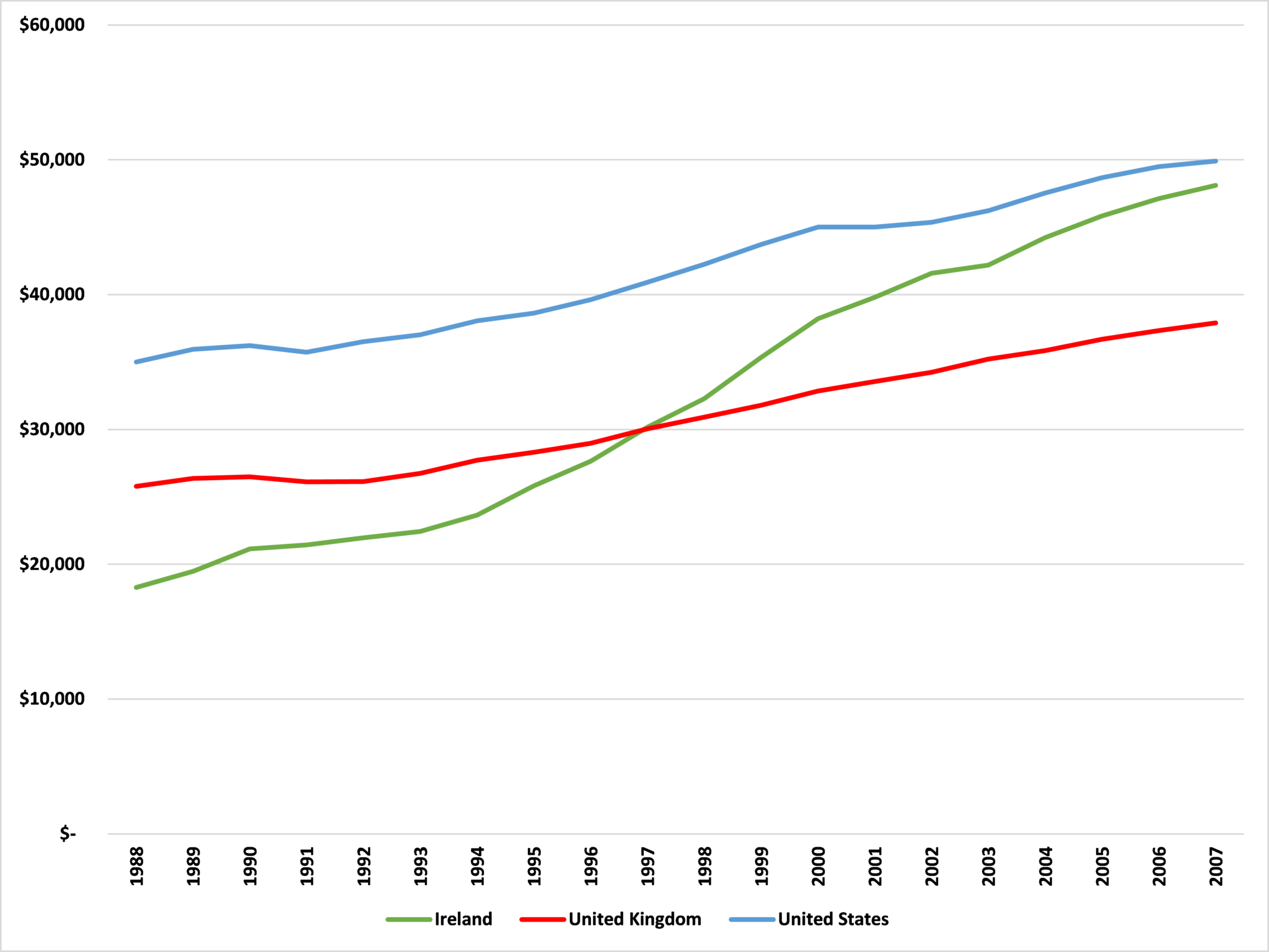

This lead to a surge in the level of Irish per capita GDP after 1993, as Figure 2 shows. In 1997, Ireland overtook the United Kingdom on this score and, by 2007, was 27 percent above it and up to 96 percent of the United States’ level.

Figure 2 – Real GDP per capita, $ 2010

Source: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

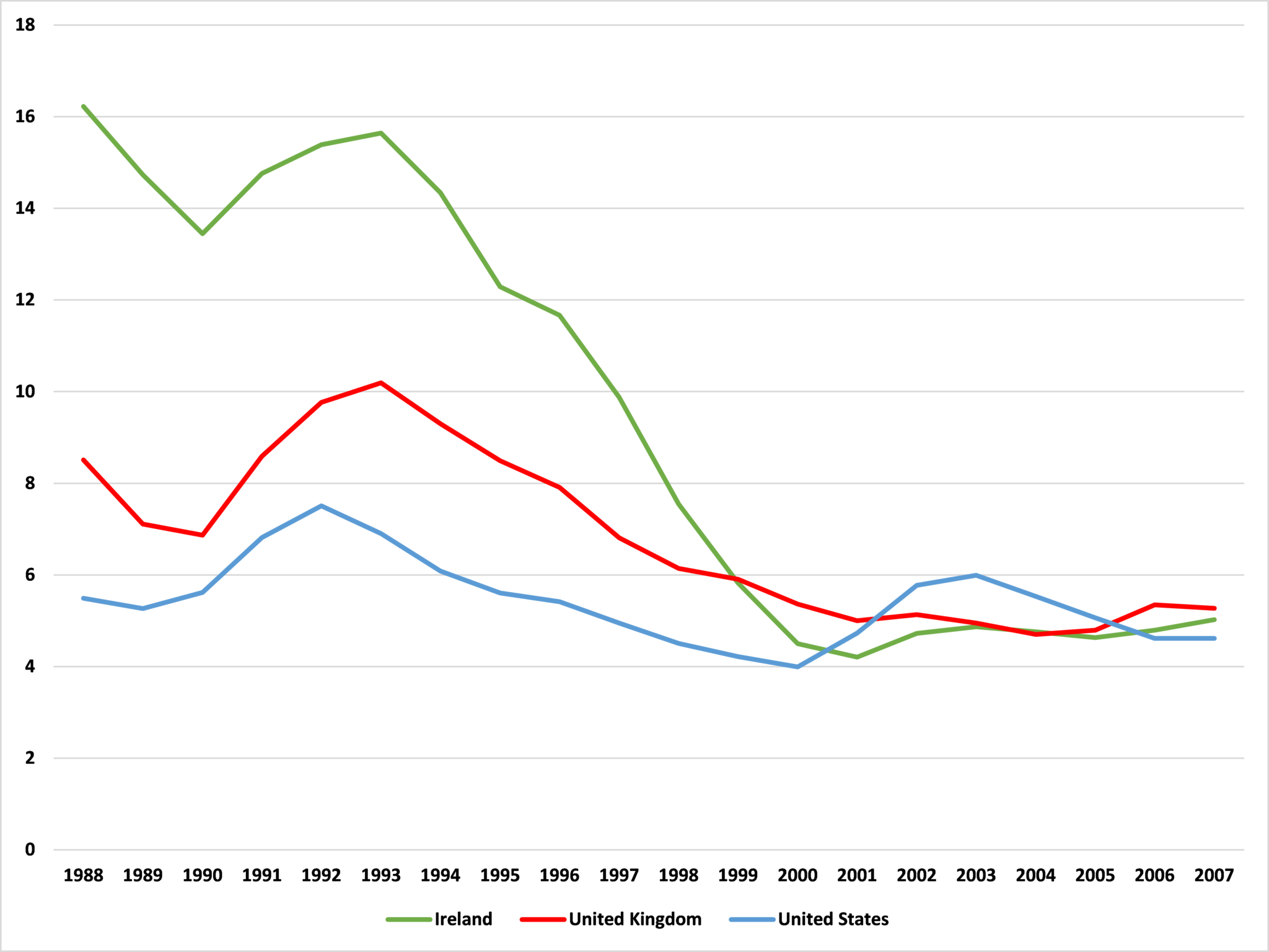

Unemployment tumbled after 1993, as Figure 3 shows. Between 1993 and 1999, about 415,000 extra jobs were filled, a rise of 35 percent, virtually all of it in the private sector. By 1999, Ireland’s unemployment rate was below that of the United Kingdom. By 2001, it was below that of the United States. So long an exporter of people, Ireland became an importer. Net migration changed from a loss of 5,000 in 1993 to a gain of 22,800 in 1998.

Figure 3 – Unemployment, percent

Source: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

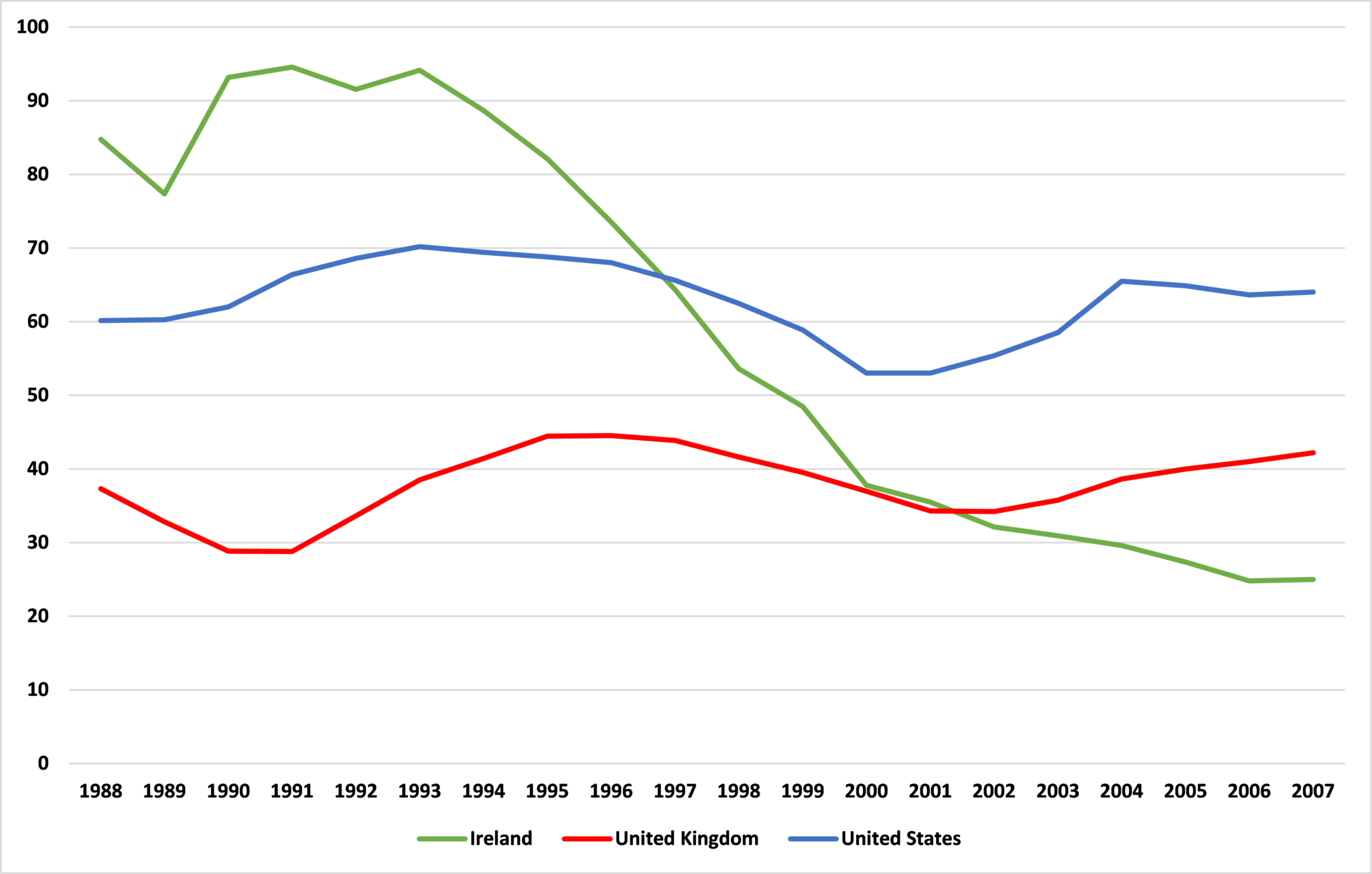

This increased prosperity worked wonders for Ireland’s government indebtedness, as Figure 4 shows. From 1993, government debt as a share of GDP fell rapidly, reaching 25 percent in 2007. By 2002, it was lower than the ratio in both the United States and United Kingdom.

Figure 4 – Government debt, percent of GDP

Source: International Monetary Fund

What happened?

The Irish hadn’t found the mysterious pot of gold. They had simply embraced sound fiscal and monetary policies.

According the economist Dermot McAleese, in the years leading up to The Economists‘ 1988 diagnosis, Ireland had been plagued by “high taxes, low confidence, high labour costs, excessive regulation and anti-competitive practices.” And, no matter how high tax rates were, spending was higher still. This meant large fiscal deficits.

By the beginning of the 1990s, it had become apparent that this could no longer continue. Acting boldly, the government — with wide support — slashed spending and made credible commitments not to engage in deficit spending or inflate the currency. It deregulated and drastically lowered tax rates. The 2002 Index of Economic Freedom published by the Wall Street Journal and The Heritage Foundation, ranked Ireland the world’s 4th freest economy.

McAleese argued the importance of getting government spending under control.

The espousal of fiscal rectitude and new consensus economic policies was not in fact new. What was new was the decision to attack the debt by controlling public spending, rather than by increasing taxes. For a small, open economy, curbing public spending proved a far more productive way forward. It created room for tax cuts while simultaneously lowering the debt ratio. Another ploy was the introduction of a tax amnesty. Following on the high tax policy of the 1980s and the reorientation in fiscal policy, it proved hugely successful in terms of revenue generation. Domestic interest rates fell steeply as investor confidence grew, thus starting off that rare occurrence in modern economics, an expansionary fiscal contraction. Fears that strong fiscal contraction would prove deflationary were confounded, though precisely why this was so remains the subject of controversy.

Deregulation unleashed rapid growth in Irish services. This sector had traditionally been neglected in favor of manufacturing. According to McAleese,

The error of this view in a small open economy became apparent after the liberalisation of public utilities and transport promoted by the EU. Access fares to Ireland fell as airline competition was introduced, giving tourism a significant boost. In the same way, explosive growth in the telecom sector followed relaxation of the state-owned monopoly’s control of the domestic market.

One of the salient features of Ireland’s economic boom was its low corporate tax rate. Until the 1990s, the standard rate of corporate profits tax (CPT) was 50 percent with a 10 percent rate on all corporate profits for export-oriented manufacturing and traded services. By 1982, over 80 percent of companies who located in Ireland cited the taxation policy as the primary reason they did so. Under pressure from the European Union, Ireland replaced this system in 1997 with a 12.5 percent rate of corporation tax for trading income from Jan. 1, 2003. And these low rates brought high revenues. In 2004, Corporate income taxes accounted for 13% of all tax revenue in Ireland compared to 6% in the United States and 8% in the United Kingdom.

But other taxes were cut too. As economist Sean Dorgan argues, since 1987

…personal tax rates have been reduced progressively from a base rate of 35 percent to 20 percent and from a top rate of 58 percent to 42 percent. Tax bands (brackets) have also been broadened so that the higher rate now applies to higher income levels than before. The power of low rates was also shown when the 40 percent capital gains tax rate was halved in 1999 to 20 percent and revenue increased by 50 percent in one year and by 270 percent over three years.

All of this, remember, at a time when government debt was falling rapidly.

And then came the crash…

The story of Irish economic success was easier to tell ten years ago. Then, the Irish economic boom turned to hideous bust. In 2008, GDP shrank by 4 percent. The following year it shrank by a further 5 percent. Unemployment rose and so did government debt. By the time GDP per capita started growing again in 2010, it was back below the level of 2004.

Some were quick to blame Ireland’s low tax and light regulation policies for this calamity. The reality was rather different. As the economist Patrick Honohan wrote in a paper titled ‘What Went Wrong in Ireland?‘,

Until about 2000, the growth had been on a secure export-led basis, underpinned by wage restraint. However, from about 2000 the character of the growth changed: a property price and construction bubble took hold…Among the triggers for the property bubble was the sharp fall in interest rates following euro membership

In short, there had been a good Celtic Tiger, based on sound money, low taxes, and light regulation, which had been replaced by a bad Celtic Tiger based on cheap credit following Ireland’s entry into the euro. True, there was much to condemn in the excesses of the boom’s later stages, but the fiscal and regulatory policies which had spurred a decade of solid growth were not among them.

What happened next?

Fortunately, the bubble and bust hadn’t killed off sensible economic policy making in Ireland. Faced with the downturn, the Irish government, admittedly with little choice thanks to its European partners, went against the Paul Krugmans of this world and attempted to reduce borrowing and restore growth with spending cuts rather than increases or higher taxes. And it worked. As economists Alberto Alesina, Carlo A. Favero and Francesco Giavazz argue in a recent article,

Following the financial crisis, the two countries that adopted spending-based austerity and did better than the rest of the sample were Ireland and the United Kingdom, despite the huge banking problems in the former

Among other things, Ireland is famous for its stories. The story of the Irish economy in the last 30 years highlights the importance of sound fiscal and monetary policy and the growth potential that these can unleash. It is a story we could all do with considering.

In the meantime, for tomorrow, lá fhéile Pádraig sona dhuit.

John Phelan is an economist at the Center of the American Experiment.