Wind Produced 4 Percent Less Electricity Through June 2019 than Through June 2018, Despite More Turbines Online

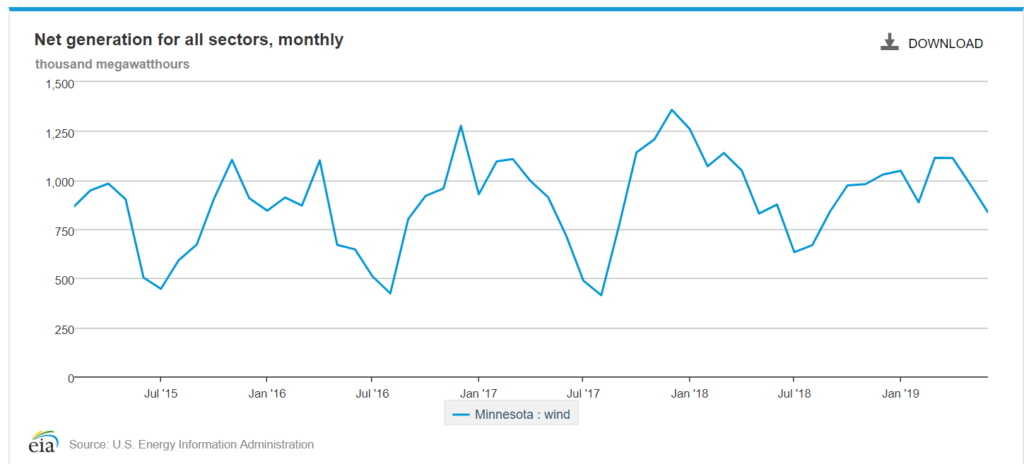

Wind generation through June of 2019 was actually 4 percent lower than through June of 2018, according to Energy Information Administration data. This decline in output comes even though there are more turbines in operation today than there were at this time in 2018.

The year-over-year decline in 2019, to date, is due to lower wind production in January, February, March, and June, compared to 2018. The decline is likely due to a variety of factors including weather, turbine degradation, and possibly curtailment of wind facilities when the grid was constrained.

Weather is the most likely culprit for lower wind output year-to-date in 2019 relative to 2018. It was too cold to operate wind turbines during the polar vortex, and wind electricity output during the cold snap was further hobbled by low wind speeds. It’s also important to note that there will be significant variation in wind output over a given period of time because weather systems are chaotic and always changing.

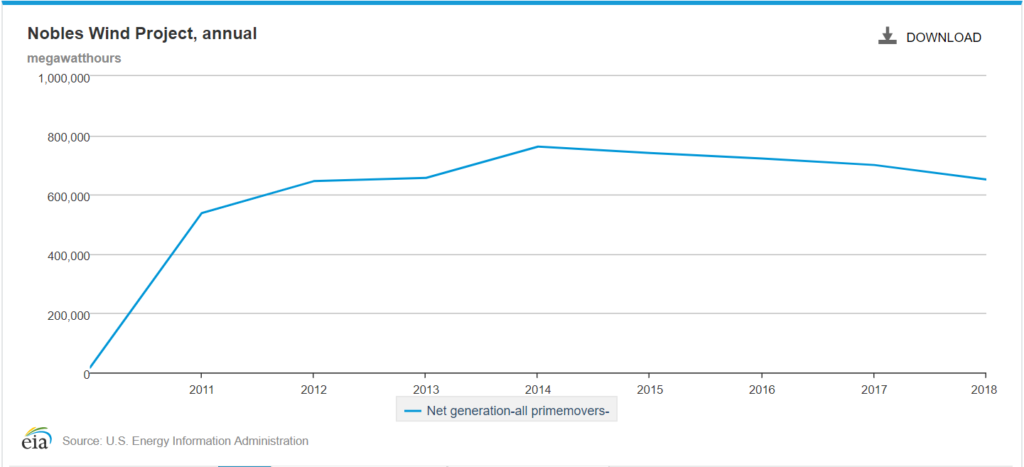

Degradation may also be playing a role, but I think this has less to do with turbine operation than weather variation. The graph below is from EIA showing production at the Nobles Wind facility from 2010 through 2018. It shows 2018 production was the lowest since 2013, and that production has been falling steadily since peaking in 2014.

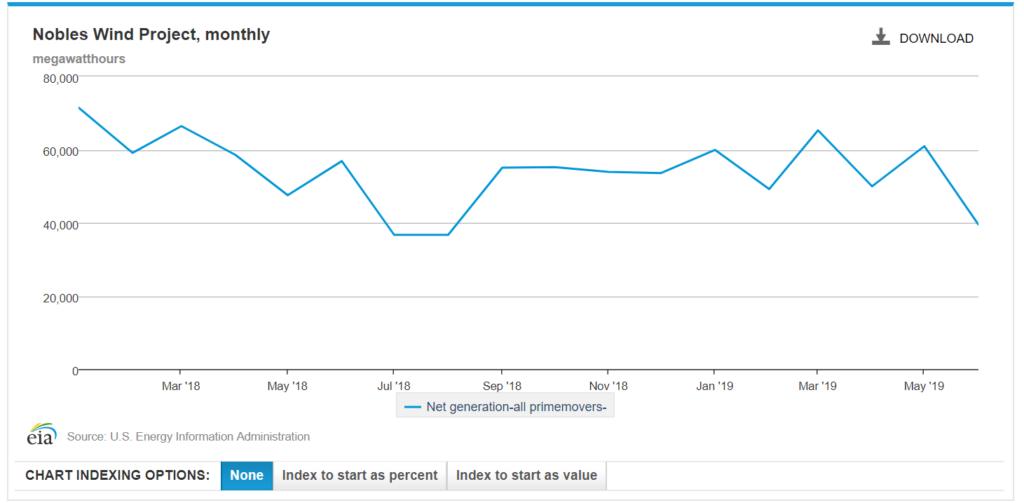

Obviously this wind facility’s output would be affected by variations in wind speeds and regional weather shifts. Here is a graph of the monthly output at Nobles starting in January 2018 and running through July 2019. As you can see, wind production at Nobles has been lower in January, February, March, April, and June of 2019, compared to theses same months in 2018.

The result is that electricity generation at Nobles is about 9.8 percent lower, year-to-date, in 2019 compared to 2018. While mechanical degradation may be playing some part in this story, the declines in output at Nobles strongly correlates to statewide wind production declines, so that leads me to believe this is more of a weather problem and less of a mechanical one.

It’s hard to say whether that’s good or bad if you’re a wind energy advocate. Mechanical degradation would be fixable, but it would also suggest that wind turbines experience a significant decline in performance in fewer than 10 years of service that will require additional capital to fix.

On the other hand, the weather explanation suggests that while wind turbines may experience some decline in output due to wear and tear, this may not be the leading factor reducing output. However, this explanation shows how subject wind energy is to weather patterns, and that is something that can’t be fixed. This explanation also suggests that building more wind turbines does not necessarily result in more wind electricity, which is also inconvenient for wind industry profiteers.

The last explanation is curtailment, or companies shutting down their wind turbines because there is too much electricity on the system. This is the least likely explanation, in my opinion, because wind generation was lower in 2019 than 2018.

I’ll be watching for new data releases to keep this story current. If current trends continue, we may have a very newsworthy headline showing wind generation was lower in 2019 than 2018.