Shutting Down Boswell Energy Center Would Devastate the Iron Range Economy

Standing on the banks of the Mississippi River in Cohasset, Minnesota, the Boswell Energy Center is the most productive, lowest-cost source of electricity in the entire state.

Because Minnesota’s mining and paper industries use massive quantities of electricity, only the coal-fired Boswell plant can provide the reliable, affordable electricity needed to keep these industries running strong.

However, liberal lawmakers from the Twin Cities—and their friends in the wind and solar lobby—want to shut the plant down to reduce carbon dioxide emissions, even though doing so would have zero measurable impact on future global temperatures. It would, however, have devastating consequences for Iron Range communities.

The Boswell Energy Center in Cohasset.

The Boswell Energy Center in Cohasset.

Minnesota, Mining, and Energy

Many people who live in the Twin Cities are vaguely aware that Minnesota mines iron ore, but few understand the scale or importance of mining to the communities that develop our iron ore resources. Even fewer understand the important role that electricity plays in the process.

Thanks to the Iron Range, Minnesota produces 85 percent of all the iron ore mined in the United States, making our state the fourth-largest mining state in the nation in 2019, trailing only Nevada, Arizona, and Texas in terms of the value of minerals sold.

Mining iron consumes an enormous amount of energy. The MinnTac mine in Mountain Iron reportedly uses more electricity and natural gas than the entire city of Minneapolis. In total, the iron mining industry consumes 650 megawatts of electricity, the equivalent of 580,560 Minnesota homes.

Mining operations run 24 hours per day, 365 days per year, and each step in the mining process requires electricity.

First, rocks that can be as large as a Volkswagen are sent to the crusher and broken down into marble-sized rocks. These small rocks are then transported by conveyor to the mill room, where they are crushed into a fine powder.

The powder is mixed with water and pumped through a separator, where magnetic rollers divide the valuable iron from the waste rock. Finally, the wet, concentrated iron powder is rolled with clay inside large, rotating cylinders to form pellets that are turned into steel.

Because electricity is so vital to every stage of the iron mining process, and mines require so much of it, even a small increase in the cost of electricity adds up.

Boswell: King of the North I recently had the opportunity to tour Boswell, which is the third-largest power plant in Minnesota. What I saw was a clean, well-lit masterpiece of modern engineering, despite the constant barrage of “dirty coal” talking points from renewable energy special interest groups.

No other power plant in Minnesota generates power more often or more affordably than the Boswell Energy Center. Federal data show Boswell generated 87 percent of its potential output in 2018, making it the most productive plant, for its size, in the state. Federal data also show Boswell was the lowest-cost source of electricity.

The high reliability and low cost of Boswell are two key reasons why it is critical to northern Minnesota and should run until at least 2035.

Wind and solar advocates want to shut Boswell down as soon as possible, but the energy sources they advocate for simply cannot do the heavy lifting required of the Boswell plant day in and day out.

For example, federal data show Minnesota’s wind fleet generated just 33 percent of its potential output in 2018 because there was not enough wind. And even the most productive wind facility in Minnesota generated less than 45.7 percent of its potential output. Solar fared even worse, generating just 18 percent of its potential. Even in a best-case scenario, wind and solar didn’t work 55 to 82 percent of the time.

Many people don’t realize that the grid is not a storage device; there is no way to readily or cost-effectively store the electricity generated by wind and solar for a later date. Coal, natural gas, hydroelectric, or nuclear power must be ready to keep the lights on when wind and solar don’t show up to work.

If environmentalist legislators succeed in shutting down Boswell, its most realistic replacement would be some combination of wind, solar, and natural gas power plants, which would require enough natural gas to power the entire system in the very possible event that wind and solar generate zero electricity.

Instead of paying once for electricity from Boswell, closing the plant could result in electricity customers paying three times for electricity they use once.

Last year, Center of the American Experiment released an award-winning study, “Doubling Down on Failure: How a 50 Percent By 2030 Renewable Energy Standard Would Cost Minnesota $80.2 Billion,” which concludes that a grid powered by 54 percent wind, solar, and hydroelectric power would cause electricity prices to increase by 40 percent, relative to November 2018 prices.

Using the economic modeling software IMPLAN, our study concludes this increase would destroy nearly 21,000 jobs. These job losses would likely be concentrated in energy intensive industries such as agriculture, manufacturing, and mining, where rising electricity costs leave Minnesota companies at a competitive disadvantage relative to firms in other states and nations.

Opportunity Costs

Energy constitutes roughly 25 percent of the cost of producing iron ore in Minnesota, and the cost of electricity paid by these mines has increased by more than 60 percent on average since 2007, when Minnesota enacted its 25 percent renewable energy mandate.

Raising the price of electricity by 40 percent would increase the cost of electricity for the mining industry by approximately $227 million, the equivalent of 2,300 mining jobs paying $99,000 per year.

The $227 million price tag incurred by integrating more renewables on the grid would likely force the iron industry to shut down entirely, sending Iron Range communities into an existential crisis.

Jobs Destroyed

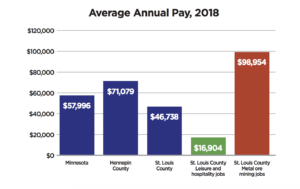

Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) show 4,006 people worked in the iron mining industry in 2018. The average wages for mining jobs in St. Louis County was $98,954, which is twice as high as the average wages for the county and 5.85 times more than wages in the tourism and hospitality industry.

The high wages paid by mining jobs amplify the economic impact of mining throughout the entire Iron Range.

Each iron mining job supported an additional 1.8 jobs in the greater economy in 2010, according to the Iron Mining Association of Minnesota. Some of these jobs are called “indirect jobs,” or jobs in support industries, such as the Mesabi Radial Tire shop in Hibbing that sells the massive tires used on mining equipment.

Other jobs are known as “induced jobs” because they are the product of miners and people employed in support industries who spend their paychecks in the broader economy at places like hospitals, grocery stores, and bakeries.

If each mining job supports 1.8 other jobs, we can estimate that the mining industry supports 11,216 jobs throughout northern Minnesota. Kelsey Johnson, the head of the Iron Mining Association, says the estimated number is even higher, with 16,000 jobs supported by the iron mining industry.

All of these jobs are at risk if the industry goes away—a distinct possibility if Boswell shuts down before the end of its useful lifetime.

Big Fish, Small Pond

The closing of a mine devastates the community around it, impacting churches, schools, businesses, and community groups. Parishioners have less money to support the church, school enrollment falls and funding disappears when people move their families to other areas to find employment. Small businesses on Main Street close their doors, and local charities like the Lion’s Club have fewer resources to help those in need.

While Minnesota produces 85 percent of the iron ore mined in the United States, this accounts for just 1.6 percent of the global total and means Minnesota’s iron industry must compete on a global scale with other producers.

Any increase in costs puts our iron industry at a disadvantage relative to producers in China and India, two nations that are investing heavily in coal-fired power plants. For example, China is building the equivalent of 185 Boswells, and India is building 87. And while each of these 272 new coal plants will emit carbon dioxide, life is about tradeoffs. The people who want to shut down Boswell to reduce carbon dioxide emissions refuse to admit that they are willing to destroy the mining industry in Minnesota by shutting down the plant. If the iron ore isn’t mined in Minnesota, we would end up importing it from China or India—where it was mined using coalfired electricity.

Such a trade-off would impact the livelihoods of thousands of hardworking Minnesotans and devastate their communities for a symbolic reduction in carbon dioxide emissions. This trade is simply unacceptable.

HibTac Tour

I have also had the opportunity to tour the facilities at the Hibbing Taconite company, locally known as the HibTac mine. The facility began pelletizing iron ore in 1976, injecting $449 million into the Iron Range economy, including the $107 million paid in annual wages to the mine’s 735 workers.

One worker guided my tour through the facility on a cold, windy day in January. Wearing a hardhat, steel toed boots, and earplugs, we first watched a mandatory safety video before signing liability waivers and then heading to the mill room, where large rotating rock crushers the size of houses spin like the gears of a clock to turn marble-sized rocks into a fine powder.

After watching the crushing and the separating, we returned to the area where the tour began, and I asked the guide how long he’d been working at the mine. “Thirty years,” he told me. “And everything I was able to give to my daughters was because of this place.”

Pep’s Bake Shop

It isn’t just mineworkers who stand to lose their means of putting food on the table. The ripple effect of losing Boswell and the mines would also impact the people who, literally, work to make the food we place on our tables.

Pep’s Bake Shop is a bakery located in downtown Virginia, Minnesota.

As you approach the entrance, there’s a sign on the door welcoming steel workers into the store. Resting on the counter past the glass cases filled with doughnuts is a tip jar that reads, “You’re never late if you bring donuts.”

Allison and Laura Collins, the mom and daughter team that runs Pep’s Bake Shop in Eveleth.

Allison and Laura Collins, the mom and daughter team that runs Pep’s Bake Shop in Eveleth.

Pep’s Bake Shop has been family-owned for three generations. The woman behind the counter has been helping her mother at the shop for the last 12 years, and her mother has been working at the bakery for 24 years. The daughter emphasized the importance of the mining industry to the area, noting that many of her customers are miners or the families of miners.

Clean, Beautiful Boswell

Environmentalists may concede that closing Boswell would hurt the economy of northern Minnesota, but they argue that the costs are worth it because “it would save the environment.”

However, it is highly likely these people have never been to Boswell. Wild rice flourishes just upstream of the plant. Minnesota Power, the company that owns Boswell, hosts an annual deer hunt for veterans on the company’s property.

Author Isaac Orr stands next to a turbine and generator inside the Boswell Energy Center in Cohasset.

Author Isaac Orr stands next to a turbine and generator inside the Boswell Energy Center in Cohasset.

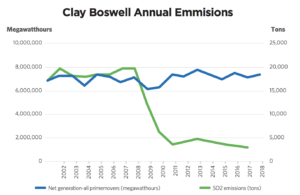

Pollution control technology has made the air quality near the coal plant cleaner than ever. Sulfur dioxide emissions have fallen by more than 75 percent since 2008, and Minnesota’s air meets all federal air quality guidelines, which are designed to protect the most vulnerable populations. Traditional air pollution has also been solved through technology.

But these pollutants aren’t driving the campaign to close Boswell. It is being driven by climate change activists and the desire to eliminate carbon dioxide emissions associated with the plant.

The Boswell plant did emit an estimated 7.8 million metric tons of CO2 in 2018, according to federal data. But using the same logic the Obama administration used for the Clean Power Plan—widely considered to be its signature climate change regulation—closing down Boswell would only avert 0.0002 degrees C (0.00036 degrees F) by 2100, an amount far too small to measure.

Conclusion

Politicians in St. Paul looking to justify their favored policy idea do so by referring to climate change as an “existential crisis.” But those who call for the closure of Boswell under this claim are trading an immeasurably small reduction in future global temperatures for a clear and present danger to the people and communities on the Iron Range.