A Crisis in Childcare

The high cost of childcare in Minnesota – caused chiefly by government regulation – strains families and our economy, especially in Greater Minnesota.

When Sarah Piepenburg and her husband had their first child, they tried their best to juggle childcare and work. She delayed work up until her child was phased out of infant care, which is the most expensive stage for childcare. However, when she did start working, she was merely taking home a $244 paycheck after paying childcare expenses, which did not seem worth it. Things did not get better for her and her husband when they decided to start a small business, something that had been a long-time dream of theirs. Sarah quit her job and the couple used the $16,000 they would use for childcare to start up a business. They again struggled to mix full-time care for kids with managing a business. Moreover, one of their best workers quit after they were offered a position with childcare benefits at some other corporation.

Sarah Piepenburg’s story is just one example that showcases the critical childcare crisis affecting numerous working parents around Minnesota and around the country. Parents are forced to choose between staying home to take care of their children or going to work. This choice does not bode well for parents who cannot access childcare either due to high cost or shortage, as research continues to show. In 2016, two million parents of children age five and younger had to quit their jobs, not take a job, or change their job due to childcare issues. Things are worse for parents who live in childcare deserts (i.e., regions with low childcare access). More mothers in these regions end up staying home compared to mothers in non-desert areas.

From high costs to critical shortage, parents cannot catch a break when it comes to childcare. But they are not the only ones suffering. Companies also have trouble attracting and retaining working parents if they are situated in areas where childcare is expensive or in short supply. They also face reduced productivity when they have to deal with worried parents or have workers who constantly miss work because they cannot find childcare. According to the advocacy group Child Care Aware, during a six-month working period, 45 percent of working parents missed work at least once due to issues with childcare. Additionally, despite the high costs of childcare, providers scarcely make profits, and childcare workers remain among some of the lowest-paid workers in the country. These are issues plaguing everyone in the country, but Minnesota has it worse.

Costs in Minnesota

Minnesota is one of the 33 states and Washington, D.C. where infant care is more expensive than college. Minnesotans pay more for childcare than the average cost of rent. It is more than the entire income of poverty-level parents.

Minnesota currently ranks as the 4th most expensive state for infant care, behind only California, Massachusetts, and Washington, D.C. According to the Economic Policy Institute, parents in Minnesota pay about $16,087 per year

or $1,342 per month to keep an infant in childcare. The annual cost for a four-year-old is $12,252, or $1,021 per month.

The cost of infant care consumes about 21.2 percent of the median Minnesota family income. But according to the

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services guidelines, childcare is only affordable if it does not exceed 7 percent of a family’s income. By looking at income, only 5.8 percent of Minnesota families spend 7 percent or less of their income on childcare. The rest spend multiple times higher, especially for infant care, which is the most expensive. A childcare worker, for instance, would have to spend two-thirds of their earnings to put their own child through infant care.

The childcare shortage

The childcare shortage

Stories abound about parents who have to commute 30 minutes or more to find childcare services or how they have to get waitlisted at daycare centers before they can be offered a spot. Some parents even go as far as asking providers for the optimal time to have a baby with regard to available childcare. This is due to the severe shortage of childcare services in Minnesota. There aren’t enough licensed care spots for all children in need of care, especially in Greater Minnesota. In 2017, Minnesota had 346,825 children age birth to four years, but childcare capacity was only 227,792—a shortage of 119,033. The number of children needing childcare is expected to stay steady for the next 50 years.

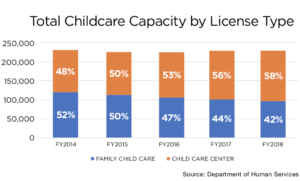

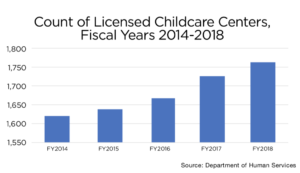

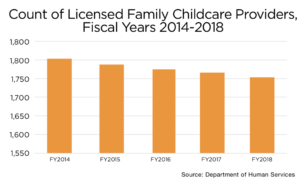

Between 2014 and 2018, overall childcare capacity decreased by 0.7 percent. While the share and number of licensed childcare centers has been growing, family-based childcare centers have been decreasing, leading to an overall capacity decrease. The increase in childcare centers has not been enough to offset the loss in capacity caused by the loss of family childcare centers (FCCs). As shown in the figure above, family childcare providers comprised 42 percent of total capacity in 2018 as compared to 52 percent of total capacity in 2014. Overall, this represents a loss in capacity of 1,671 slots in the whole industry.

Childcare workers

Childcare workers are among the lowest-paid professionals in Minnesota and nationwide. More than 85 percent of childcare workers are considered low-wage workers. The Center for the Study of Childcare Employment estimates that the average salary of a Minnesota childcare worker is $10.81 per hour or $24,556 per year. This low wage deters would-be workers from entering the profession and therefore makes it hard for providers to find and keep qualified workers. Because providers have to compete with higher-paying jobs that require no experience, they lose workers to these other jobs.

It is also important that childcare workers possess qualifications and training. But their wages do not align with the amount of training the state requires before they can start caring for children. Early learning programs, for instance, need significantly more staff than other settings, and the staff requires more professional development and ongoing training. Wages for early childhood educators have also remained stagnant, even though more child workers have attained college degrees now than ever before. It is not surprising to hear of qualified candidates unwilling to take low-paying teacher jobs in childcare.

Greater Minnesota

The increase in Minnesota’s licensed childcare centers has been concentrated in the Twin Cities, which has left Greater Minnesota lacking. Between 2000 and 2015, only the metro region experienced an increase in childcare capacity of 2 percent. To understand the issue, licensed childcare centers are expensive to establish and operate; they require higher tuition and a higher enrollment. Parents in rural areas cannot afford the high tuition often required to keep a center running. The small populations in rural areas can also be inadequate to supply the needs of maintaining a center. Greater Minnesota is, therefore, more suitable for FCCs.

Unfortunately, several factors have caused FCCs to leave the market at alarming rates. Baby Boomers, including those who own family childcare businesses, are reaching retirement age. People may be choosing other fields that have more flexible schedules and fewer hours. Low wages compared to other professions discourage people from opening FCCs. These are, however, factors that can rarely be controlled. What the state government can control is regulation. Unfortunately, FCCs are having trouble navigating the expanding – as well as changing – regulatory environment.

COVID-19

Governor Tim Walz’s stay-at-home order encouraged childcare providers to stay open and provide care to the children of essential workers. But since they have been open, providers have had to spend more money on labor to make sure there was adequate staff to do all the extra cleaning and keep sizes small. This was in addition to paying their regular overhead expenses. At the same time, providers have seen a huge drop in revenue as enrollment rates have gone down. The effect is that some providers closed their businesses for good because they could not keep up with the costs of operating while bringing in less revenue. Others have temporarily closed but might face difficulties opening back up, and those still operating are also facing difficulties trying to stay afloat. This is not such an extraordinary occurrence; it is economically impossible for any business to stay open for a long time if it is facing increased costs while bringing in less revenue. The same is true for childcare providers, but they already operate on razor-thin profit margins, so they are more fragile.

Do subsidies help?

Governments often turn to subsidies to help low-income families pay for childcare. Subsidies, however, come with their own issues and also fail to resolve other underlying challenges that face childcare. For example, subsidies do not help low-income families who are not part of the market (i.e., people whose kids are cared for by family members or who stay off work to take care of them). Subsidies also tend to increase the cost of providing care, which is in turn disadvantageous to families not eligible for financial assistance. This is because subsidies give providers no incentive to be productive or compete for business. Subsidies furthermore tend to come with increased regulations, as the government tries ways of quality control or accountability for money spent. This results in providers being driven out of the market due to the added compliance costs.

Regulation is a big cause of the crisis

Regulations are a necessary part of childcare—they are there to ensure safety and quality. But restrictive regulation contributes to the shortage as well as high prices. People are afraid to open in-house facilities, some are forced out due to too much regulation, and even employers who would like to set up childcare facilities on their premises are discouraged by the sheer number of regulations that they have to follow. Here are some of the issues with Minnesota’s regulations of the childcare industry that possibly contribute to the crisis.

1. Staffing ratios

Every state mandates staffing ratios that are legally enforced. They are there to ensure children get quality service. These ratios differ from state to state. The state of Minnesota, for instance, mandates that centers have one teacher for every four infants (six weeks to 16 months). Some states, however, allow higher ratios for infants, and they tend to cut off infants as anyone between birth to around nine to 12 months. This means centers can have larger groups for kids aged anywhere beyond nine to 12 months, which is not possible in Minnesota. And because teachers are expensive to hire as they require advanced qualifications, providers who have to hire more teachers face high costs of business, which leads to high costs of tuition for parents.

2. Strict enforcement

Childcare providers can also face strict regulations from county licensors. For example, the Star Tribune reported that providers have been cited for issues as small as a water heater being one degree higher than the maximum required temperature and for having “prickly grass.” These standards are often reinforced by the idea that they lead to quality services, which is not necessarily true. Parents have their own mechanisms for monitoring and rewarding quality, either through ratings or a willingness to pay more for highly-rated providers. All that strict enforcement does is make it harder for providers to operate.

3. Strict hiring requirements

Minnesota requires stringent qualifications for providers, which prevents people from entering the childcare industry, especially after considering the low pay. To be a teacher in Minnesota, someone with a bachelor’s degree in any field from an accredited college is required to have 1,040 hours of experience as an assistant teacher. Someone with a high school diploma is required to have 4,160 hours as an assistant teacher. It takes 2,080 hours of being an aide or student intern to be an assistant teacher.

4. Inconsistent regulatory landscape

The Minnesota Department of Health and Human Services has delegated licensing power and enforcement to county licensors. However, different county licensors can have varying interpretations of state law and therefore contribute to an inconsistent regulatory landscape. This makes it harder for providers to operate, especially if these laws are strictly enforced.

5. Increased and changing requirements

In 2013, the federal government reenacted the Childcare Block and Development Grant (CBDG) that helps low-income families pay for childcare. As part of the program, states had to enact some changes to their regulatory landscape to improve safety and quality of services. In 2014, training requirements for providers doubled from eight to 16 hours per year. As training costs doubled, so did the costs of hiring substitutes who are few and far between and are also required to have training. Additionally, training courses are hard to find in Greater Minnesota. Subsequent changes have been made in the following years, and they have included requiring everyone directly employed by a center to get a background study even if not directly involved in giving care.

Conclusion

Access to childcare is fundamental for the proper functioning of the economy. Lack of access to childcare not only affects parents and businesses but also affects the whole economy. If people cannot work or have to cut short their hours of work, they lose earnings and businesses lose productivity. This translates to a loss of GDP in the economy as well as a loss of tax revenue for local, state, and federal governments. It is imperative that this crisis is addressed, especially to ensure the smooth recovery of the economy.

Martha Njolomole is an Economist at Center of the American Experiment. She earned a Master of Arts in economics at Troy University in Alabama, where she worked as a research assistant on several projects that advanced the ideas of economic freedom and individual liberty. Martha’s upbringing in Malawi helped develop her passion for research on the social and economic advancement of economically disadvantaged people.