Apprenticeship program helps students of all ages reap success

An innovative apprenticeship program aimed at “moving the needle” on workforce development challenges in manufacturing has had great success preparing young people for skilled careers and helping older workers improve their skills. Known as the Kentucky Federation for Advanced Manufacturing Education (FAME), the work-based learning program was started in 2010 by a handful of manufacturing employers—including Toyota Motor North America—who were struggling to find “middle-skill” workers to build their talent pipeline, reports The Wall Street Journal. Its partners now include community colleges and nearly 400 employers in 13 states.

Students of FAME—a mix of new high-school grads and older factory workers well into their careers—typically spend two days a week in class and three days on the factory floor, earning a part-time salary. They learn to maintain and repair machinery; traditional subjects such English, math and philosophy; and soft skills such as work ethic and teamwork. After earning an associate degree, most work full time for the factories that sponsored them.

…

FAME graduates fill what might be called “grey-collar” jobs, which involve both traditional blue-collar manual labor and the kind of critical thinking and communication typically associated with a four-year degree.

…

The FAME program typically covers five semesters, or two years. To enroll, students must interview with employers, who consider past grades, standardized tests and demeanor. FAME graduates are a somewhat selective group: Half of FAME graduates reported that their grades had ranked in the top third of their high-school class.

A study of FAME, released by Opportunity America and the Brookings Institution, quantifies the initiative’s benefits for students and identifies what has made the work-based learning model successful. First, “there can be no effective career preparation without employers.” Employer engagement is key, and when workforce initiatives are industry-driven, it also helps ensure that educators are teaching the in-demand skills companies are looking for. Second, surveyed FAME graduates identified the program’s on-the-job training and combination of classroom learning and on-the-job training as its top valuable components, which distinguish the work-and-learn model from other programs.

In theory, students who spend time in the workplace have an opportunity to apply what they learn in class, reinforcing abstract, academic instruction with practical experience. They learn how to handle themselves on a job, absorbing the norms and habits of more mature workers. Some find a mentor who challenges and inspires them in a way no teacher has been able to. For others, the most important takeaway is motivational: their experience on the job helps them understand why what they’re learning in class matters and gives them a reason to apply themselves.

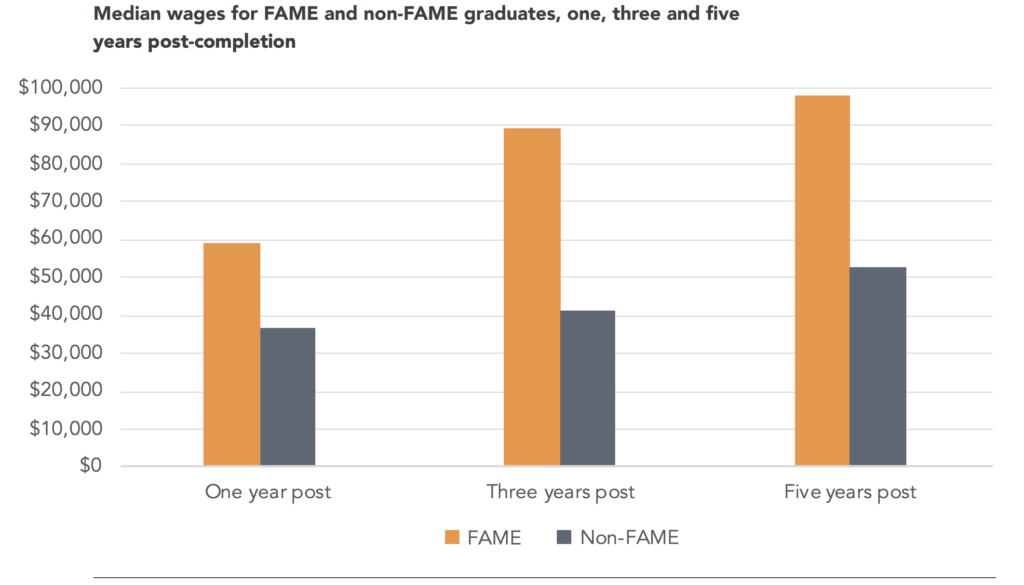

Ricky Brown, a high school drop-out who got his GED diploma for his 32nd birthday and is now a 41-year-old father of two, participated in the FAME program three years ago and is earning $72,000 a year maintaining and repairing machinery for an aluminum factory in Kentucky, according to the Journal. And such earnings are not atypical of FAME graduates. According to the FAME study, median earnings for FAME participants one year after completing the program were $59,164 a year, compared to $36,379 for student graduates of similar ages, demographics and backgrounds who did not enroll in FAME; three years after completion, FAME graduates were earning $89,360 compared to $41,085 for their non-FAME peers; five years after completion FAME graduates were earning nearly $98,000 compared to around $52,783 for non-FAME participants—a difference of more than $45,000 a year.

The Kentucky FAME model certainly offers helpful lessons on confronting workforce challenges. Other states, including Colorado, Kansas, and Indiana, have launched their own successful workforce development initiatives, which my colleague Katherine Kersten profiles here (starting on page 7). Providing individuals with real-world experience that then sets them up for a financially rewarding career is a great step toward not only driving more efficient use of human capital but also accelerating economic growth and economic mobility and giving students of all ages the opportunity to succeed in life.