Can ranked-choice voting results point toward incidents of voter fraud?

If my hypothesis is correct, then the controversial voting method would finally be good for something.

Readers will recall that I’ve been searching for evidence of voting fraud in recent Minneapolis elections, specifically, in the city’s Ward 6, which lies east of downtown. I’ve been looking for statistical anomalies, odd patterns and unlikely outcomes in voting results. Such anomalies would not represent “proof” of fraud, but should point investigators in what may prove to be useful directions.

You will also recall my work on ranked-choice voting (RCV), where voters don’t pick just one candidate in a race, but have the opportunity to rank multiple candidates in preference order (1, 2, 3, etc.). Minneapolis has adopted the voting method for all of its municipal elections.

I’ve long suspected that the practice of “ballot harvesting” exists in Minnesota. Here, I’m using the harvesting term to describe the process where an absentee/mail-in ballot is requested on behalf of a voter, the requested blank ballot is retrieved from the mail, the ballot is filled out, the ballot is returned via mail or drop-off to election authorities, and the “vote” is counted on election day.

The “voter” involved may well be a legitimate, living, qualified, non-felon, American citizen, properly-registered, legal voter. The problem arises in the extent to which a third-party handles the ballot and the level of involvement, if any, of the underlying voter in casting the ballot.

This third-party “mishandling” of absentee ballots was the issue at the heart of the perjury conviction Federal authorities obtained against Muse Mohamed of Minneapolis in May 2022. Mohamed is the brother-in-law of sitting state Sen. Omar Fateh (DFL-Minneapolis). In August 2020, Mohamed was working as a campaign volunteer for Fateh in the Democratic-party primary election.

Based on the set of facts in the Muse Mohammed case, I began to wonder whether improperly harvested ballots would look differently than other ballots: could you see signs of ballot harvesting in election results?

One hypothesis I had was that ballots harvested by an Indvidual campaign would feature votes in that single race, with other contests on the same ballot left blank. (See this example for illustration.)

In a ranked-choice voting contest, a priori, I would expect to see a larger number of harvested ballots that skipped the 2nd- and 3rd-choice preferences, and only recorded a vote for 1st-choice. If you are a busy harvester, why take the time to fill out extra lines that don’t help your candidate? Or in the alternative, you vote your guy for all three slots, just to make sure.

With all the attention on Minneapolis, Ward 6, I decided to take a look at ballots cast in last year’s race for city council.

Last year, all thirteen seats on the city council were up for election. To create a control group/base case to compare Ward 6 results against, I chose Wards 7 and 8, the only other races to feature multiple candidates and where the contest extended beyond the first round of counting.

Thanks to the Minneapolis elections office, we can test this RCV hypothesis. After each municipal election, the city publishes a spreadsheet for each race tallying the how each ballot cast was marked. Because ranked-choice voting is so inherently confusing, please read carefully:

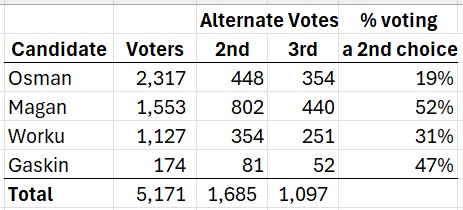

In the 2023 in Ward 6, four candidates ran and a total of 5,171 votes were cast. No one had a majority after round 1 of counting. After tabulating the alternate choices of voters backing the 3rd- and 4th-place finishers, it was determined that incumbent council member Jamal Osman won.

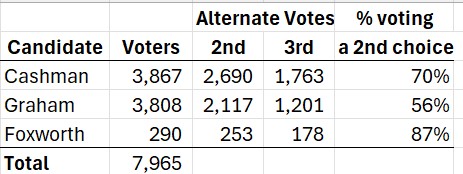

In Ward 7, three candidates ran for this open seat. A total of 7,965 votes were cast. After counting the 2nd-choice preferences of the voters supporting the 3rd-place finisher, Katie Cashman was declared the winner.

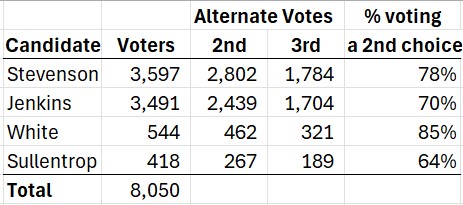

In Ward 8, four candidates ran and a total of 8,050 votes were cast. After counting the alternate choices of voters backing the 3rd- and 4th-place finishers, incumbent member Andrea Jenkins came from behind and was declared the winner by 38 votes.

In Wards 6 and 8, neither winner was able to achieve a majority in the final count.

What’s interesting about these three races is comparing the differing behavior of voters in the three contests.

Consider the following table of data from Ward 6. It requires an explanation:

Ward 6 runner up Kayseh Magan received 1,553 first place votes from his supporters. The figure of 802 in the next column is not the number of 2nd-place votes Magan received, but the number of 2nd place votes Magan supporters bestowed on other candidates in the race (including write-ins).

In contrast, of the voters supporting Jamal Osman in round one, fewer than one-fifth (19 percent) of his backers bothered to pick an alternative candidate on their ballots.

Compare this outcome to the results from Ward 7:

The runner-up Scott Graham received 3,808 first-place votes. Most of Graham’s supporters chose an alternate candidate. Supporters of the other two Ward 7 candidates picked alternatives at even higher rates.

Here are the results for Ward 8:

Bob Sullentrop finished 4th in the Ward 8 contest with some 418 first-place votes. Nearly two-thirds of his voters picked other candidates in the 2nd- and 3rd-place slots. Voters supporting the other three contenders cast alternate votes at even higher rates.

After round one of counting, the alternate votes from Sullentrop and White supporters were redistributed to the finalists Stevenson and Jenkins. These second-chance votes proved enough to give the incumbent Jenkins an upset victory.

It’s clear that something different is going on in Ward 6. If pressed, one could imagine a range of narratives to explain away the relative low rate of Ward 6’s 2nd- and 3rd-choice votes. Perhaps the citizens of Ward 6 are unique in their dislike of the RCV method and simply refuse to participate. Or Ward 6 voters find RCV more confusing than voters of other districts and are unable to navigate their ballots.

The Ward 6 race was bitterly fought in 2023 with no love lost among the candidates. Perhaps that animosity trickled down to their supporters, who couldn’t see themselves clear to backing anyone other than their man.

On the other hand, the identification of statistical anomalies in voting results does not prove voting irregularities.

But it should make you wonder and want to dig further.