Cato Institute asks: Do states need income taxes?

Recently, I asked ‘What do states without an income tax do?‘ Chris Edwards of the Cato Institute asks a similar question about the states without an income tax: “How do they run their governments without it?”

The nine states without an individual income tax are Alaska, Florida, Nevada, New Hampshire, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Washington, and Wyoming. The states are in every part of the country and have different industry mixes, histories, and political cultures. What they have in common is providing needed state‐local services to their residents without complex, anti‐freedom, and anti‐growth individual income taxes.

Most of the nine run leaner and more efficient governments than most other states. They only partly make up for the income tax revenue gap with other revenues. In terms of overall tax burdens, eight of the nine states are toward the bottom of the 50 states and Washington is in the middle.

However, Alaska and Wyoming are different because revenues related to their energy industries have induced them to fund bigger governments. They spend more and have larger bureaucracies than most other states, and thus do not provide fiscal models that other states could or should follow. That leaves seven states without individual income taxes that others may seek to emulate.

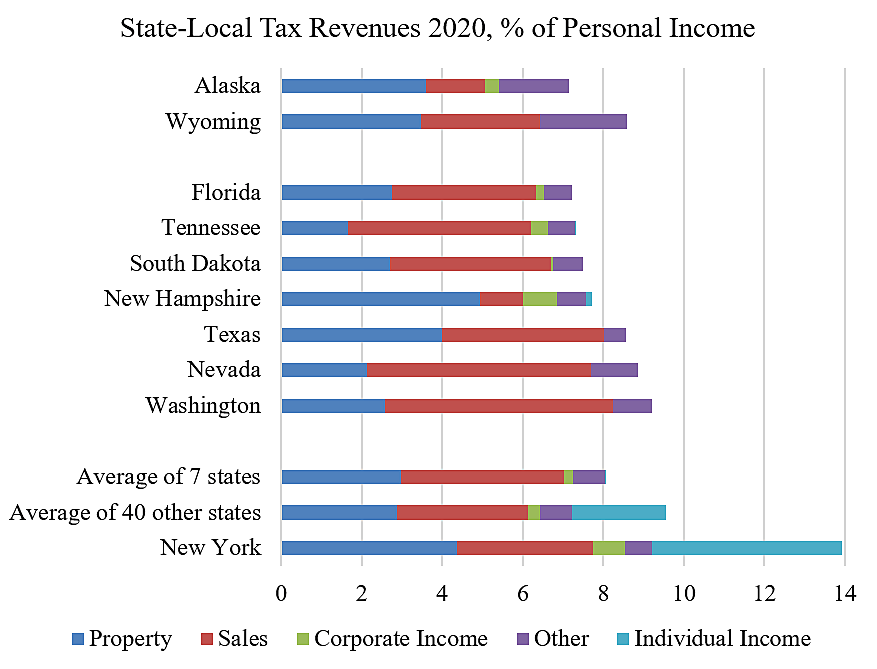

The chart shows state‐local taxes in 2020 as a percentage of personal income for the seven states, as well as Alaska and Wyoming, New York, and the other 40 states. This tax‐to‐income metric accounts for different state populations and income levels. New York may need to pay school teachers more than does a lower‐cost state such as Florida, but the metric roughly adjusts for this. Data is from a TPC table based on Census figures.

Some observations:

Total taxes in the seven states average 8.1 percent of income. The average in the 40 other states is 9.6 percent. Thus, the lack of individual income tax restrains the overall tax burden.

Property and sales taxes are higher in the seven‐state average than the 40‐state average, but the overall tax burdens are lower.

Among the seven, Washington has the highest taxes, but the burden is still below the average of the other 40. Since at least 2005, Washington has had leftist governors who scored at the bottom of the Cato Fiscal Policy Report. The lack of income tax has likely been a barrier to further government expansion in that state.

New Hampshire recently repealed its tax on interest and dividends, so residents will soon be fully free of individual income taxation.

New York has the highest state‐local tax burden in the nation at 13.9 percent, which is almost twice Florida’s burden of 7.2 percent. New York’s individual income tax raises 4.7 percent of income—twice that raised by the average of the other 40 states. New York also has higher property, sales, and corporate tax revenues than the other 40 states.

My favored tax structure is a property tax to fund local government and sales tax to fund state government, and that’s about it. In some cases, local sales taxes and fees for government services are appropriate. The seven states have close to this ideal tax structure, but some of them have corporate income and gross receipts taxes that should be repealed. These business taxes are economically damaging and impose nontransparent burdens on individuals.

“Repealing state individual income taxes is a good goal,” Edwards concludes.

The seven states are diverse, but they’ve all made it work. Residents get the state‐local services they need, but at lower cost. Within the seven states, policymakers should cut business taxes, as Governor Chris Sununu of New Hampshire has done.

The combination of property taxes, sales taxes, and fees for some services should be enough to run state and local governments. If policymakers deliver needed services in a lean and efficient manner, they can free their residents and businesses of complex and damaging state income taxes.