Despite risky behavior, pension funds are coming up short

I have several good buddies who make sure I see I keep up with my pension math. So earlier this week, I got a number of friendly pings pointing to a Wall Street Journal article on how public pension funds are taking greater risks to achieve assumed rates of return this week (Pension Funds Pile on Risk, Wednesday June 1, 2016).

The WSJ article was prompted the release of a new study by Callan Associates, Inc. an advisor to large investors like pension funds.

The study noted “a more volatile mix of stocks, real estate and private equity needed to match prior returns” and used an average assumed rate of return of 7.5% to demonstrate just how hard that return is to achieve these days.

For some perspective, I note that 7.5% is well above what private pension funds are shooting for these days. And 7.5% is a full half percentage point below Minnesota’s newly adopted assumed rate of 8 percent for most of the major funds as of 2015. Minnesota’s Teachers Retirement Association just agreed to drop its rate from 8.5% to 8% this past legislative session. Fortunately, Minnesota is the nation’s outlier in this regard.

I also note that the Treasury Department just rejected the work-out plan submitted by Central States Pension in part because the plan’s success is dependent on an assumed rate of return of 7.5%. Treasury called 7.5% “significantly optimistic.”

There is a growing recognition, by the Feds and even big Blue States like California and New York, that past returns are not achievable. But many public pension funds have yet to catch up with reality. I supposed this is why someone thought it was a good idea to do a study for those folks who think that the market’s performance over the last 30 years is going to be repeated over the next 30 years.

Here is how much the world has changed: According to Callan Associates, in 1995, a portfolio made up of entirely of bonds could earn a return of 7.5%. By 2005, pension funds had shifted to just 50% bonds, and by 2015, after years in a zero interest environment, most funds are holding about 12% bonds. The typical public pension portfolio is now very heavy on equities with substantial percentages of real estate and private equity. “The amplified bets carry potential pitfalls and heftier management fees.”

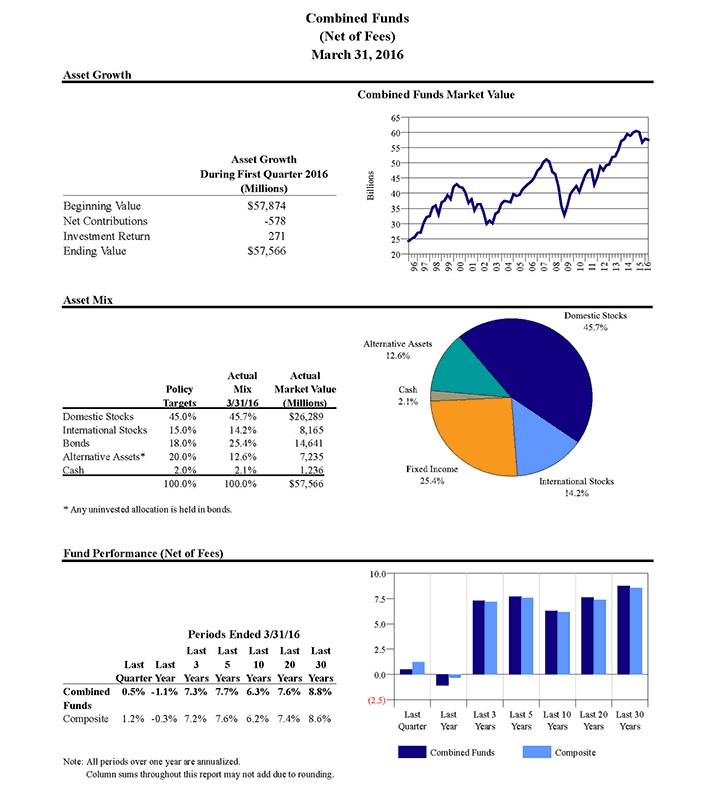

Below is a screen shot of Minnesota’s March 31, 2016 State Board of Investment performance report. As you can see, the state has 60% equities (46% domestic/14% international), 25% bonds (with a goal of 18%), 13% alternatives (with a goal of 20%) and the rest cash.

How about results? That mix produced negative returns last year (-1.1%) and between 6 and 7 percent over the last ten years, well below the goal of 8.0% to 8.5%.

That means that Minnesota, which admits to a $17 Billion unfunded liability, has not and is not collecting enough in contributions to cover the promises it has made, all the while giving out a generous COLA to current retirees.

Risky public pension portfolios is not a new concern: pension watchers have been jumping up and down for years, pointing to this clear trend and the attendant hazards.

But we have been largely ignored because, even though everyone says they care about retirees, pensions bore most people. Very few of you made it this far in this article.

And the political pain to fix pensions is excruciating. While most states have well-intended staff and legislators, it is public union officials from AFSCME and SEIU who are calling the shots. The unions dominate the pension fund boards; even in state like Minnesota where pensions are not a subject of collective bargaining, the unions are directing pension policy.

And if legislators push them too hard, the unions target them and often take them out.

That is why, depending on what assumptions you use, the United States has between $1 Trillion and $3 Trillion in unfunded pension liabilities—and that is just the public sector. It does not include all those labor funds that are going broke and angling for a Congressional bailout.

If we think the 2016 election is exciting, wait until the pension tsunami hits.