Even left wingers embrace the Laffer Curve now

Tax beards because you want fewer beards. Tax cigarettes because you want less smoking. Tax alcohol because you want less drinking. Tax labour…

Can you finish the sentence?

As I wrote on Tuesday, tax is a negative or disincentive. If you tax something, you get less of it. And policymakers, when taxing beards, cigarettes, or alcohol, are not only admitting this but banking on it.

Tobacco tax rates and revenues

A small tax on tobacco will have little effect on your consumption. But as the tax rises you will alter your consumption accordingly. You may choose to cut back (which is what policymakers are hoping for). You may choose to buy illegally. You may choose to buy from a jurisdiction with lower tax rates. As MPR News reported recently,

With cheaper cigar prices online and in neighboring states, tobacco retailers in Minnesota are excited about the tax cut.

[Chuck] Peterson [of Maplewood Tobacco and E-Cig Center] says cigar sales traditionally pick up this time of year. He thinks it will get even better with the lower taxes.

“People wouldn’t be more inclined to go to, say, Wisconsin or North Dakota or another state to buy their cigars,” Peterson said. “They can just come up the street here, a five or 10-minute drive, and get a nice stick for a fair price.”

So, with a high tax rate on tobacco, Minnesotans buy their smokes out of state, paying tobacco tax there. Minnesota gets no tobacco tax revenue from these purchases. But, by bringing the tax rate down, Chuck Peterson argues, Minnesotans will be more likely to buy their smokes in-state and pay tobacco tax here.

Simply put, by reducing the disincentive effect, a cut in the rate of tax might lead to an increase in the revenue it generates.

Tobacco taxes and the Laffer Curve

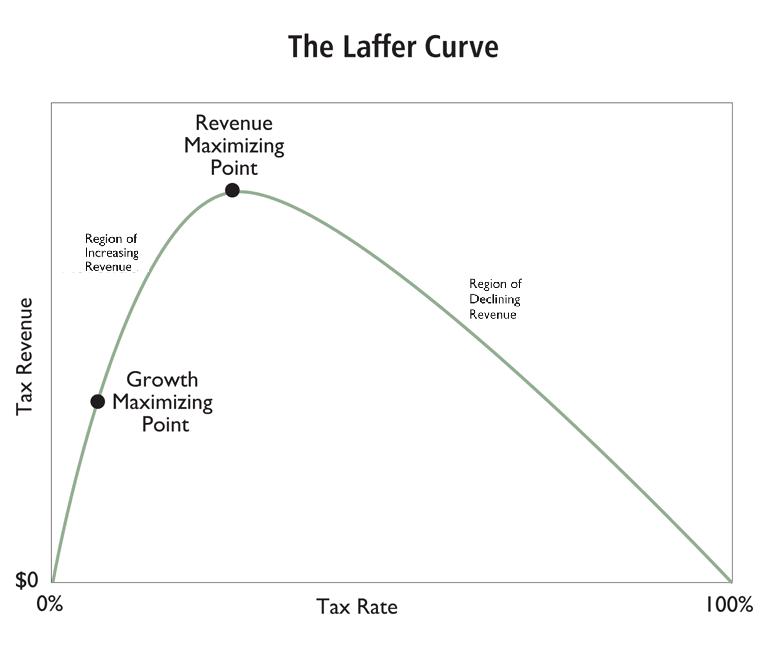

This insight was famously modeled as the Laffer Curve (shown below), named after the economist Arthur Laffer.

You can see Chuck Peterson’s point illustrated here. Tobacco tax rates in Minnesota are currently somewhere to the right of the Revenue Maximizing Point. By reducing rates and reducing the disincentive effect, the Minnesota state government might encourage those smokers buying illegally or out of state, where they pay no tobacco tax, to buy their smokes legally in Minnesota and pay tax here.

Income taxes and the Laffer Curve

The same applies to alcohol or income taxes. If income tax rates, for example, are to the right of the Revenue Maximizing Point, then reducing those rates will increase revenues. This happened in the US in the 1920s. It happened in the US and UK in the 1980s.

…in 1980, when the top statutory income tax rate went up to 70 percent, the share of income taxes paid by the top 1 percent of taxpayers was just 19.3 percent. After Ronald Reagan’s tax cut of 1981, which reduced the top rate to 50 percent — a massive give-away to the wealthy according to those on the left — the percentage of income taxes paid by the top 1 percent rose steadily.

By 1986, the top 1 percent’s share of all federal income taxes rose to 25.7 percent. That year, the top statutory tax rate was further cut to 28 percent — another huge-give-away, we were told. Yet the share of income taxes paid by the top 1 percent continued to rise. By 1992, it was up to 27.5 percent.

…

…according to Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs, the share of total income taxes paid by the top 1 percent of taxpayers was 11 percent in the United Kingdom in 1979, when the top income tax rate was 83 percent. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher cut that rate to 60 percent, and by 1987 the share of income taxes paid by the top 1 percent had risen to 14 percent. The top rate was cut again to 40 percent, where it still stands, and the share of income taxes paid by the top 1 percent continued rising to a current level of 21 percent.

It happened again recently when Britain reduced its Corporation Tax rates and top rate of income tax.

‘Progressives’ learn to love the Laffer Curve

To repeat, this logic is a staple of public finance. But, for some reason, some people who apply this logic in some cases refuse to apply it in others. Theory that so-called ‘liberals’ and ‘progressives’ would happily apply to alcohol or tobacco taxation, they denounce as “snake oil” when applied to income taxation.

But that is increasingly not the case. Nowadays, some on the political left seem not only to accept Laffer’s logic, but to embrace it. Indeed, the fact that high tax rates might reduce economic activity, as Laffer predicted, is now seen by some as an argument in their favor.

In his book Capital in the Twenty-First Century, economist Thomas Piketty explicitly acknowledges that high tax rates do not translate into high tax revenues. “A rate of 80 percent applied to incomes above $500,000 or $1 million a year would not bring government much in the way of revenue, because it would quickly fulfill its objective: to drastically reduce remuneration at this level” he writes. “[T]hese high brackets never yield much”, he continues, the point is “to put an end to such incomes and large estates”.

This is an explicit embrace by Piketty of Laffer’s logic. He acknowledges that there is a downward slope, that the curve, in fact, curves. Piketty and Laffer agree that higher tax rates depress taxable activity. Where they disagree is that Laffer sees this as a negative outcome and Piketty sees it as a positive.

This is a penal approach to taxation which contrasts with an approach designed to maximize revenues. Louis XIV’s finance minister, Jean Baptiste-Colbert, is supposed to have said that “The art of taxation consists in so plucking the goose as to procure the largest quantity of feathers with the least possible amount of hissing”. Not so for penal taxers such as Piketty. The art is now to procure the largest quantity of hissing regardless of how many feathers you get.

John Phelan is an economist at Center of the American Experiment.