Even with 5 extra years of education, a quarter of 12th grade students would still remain undereducated at graduation

As the class of 2023 prepares for the momentous occasion of high school graduation, many will unfortunately be completing their K-12 journey without sound academic knowledge and skills. According to the spring 2022 Minnesota Comprehensive Assessment, nearly 59 percent of then-11th graders weren’t able to do grade-level math.

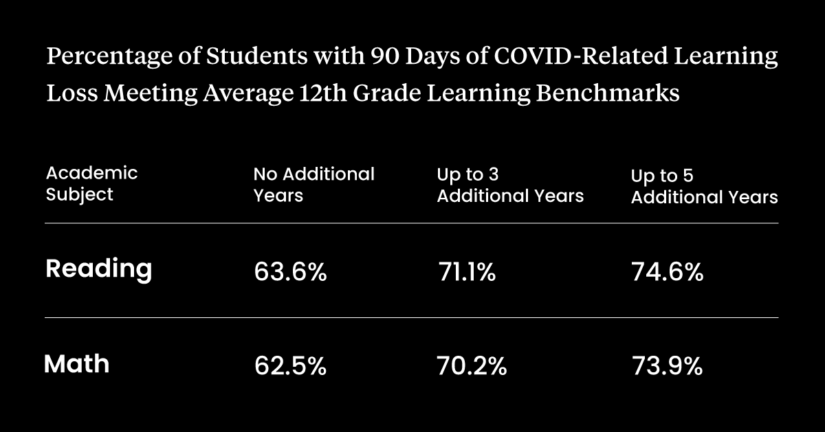

But even with five extra years of public school education, still only about 75 percent of students would be at grade level by their high school graduation, with one quarter remaining undereducated, according to recent research by The 74’s team at the Center for Research on Education Outcomes (CREDO) at Stanford University.

CREDO analyzed learning patterns in 16 states to estimate how current recovery efforts to address learning loss from school closures will impact students’ academic careers in reading and math by the end of their senior year in high school. Spoiler: “The most widely used solutions will not diminish our students’ learning deficits.”

Our research assumes that the pre-pandemic pace of learning for individual students is the best that can be expected in the post-COVID years. Using longitudinal student data, we calculated each student’s historical POL [Pace of Learning] and, based on those measures, projected outcomes under different learning loss scenarios. Here, we assume students have lost an average of 90 days of learning due to COVID-19, which other research has corroborated. We then considered the effects of additional time, measured in extra years of schooling.

…

Without additional learning time, fewer than two-thirds will attain that level in either subject. But more critically, even many years of additional instruction will yield only a small improvement. Even if schools offer an additional five years of education (assuming students would partake), only about 75% of students will hit that 12th-grade benchmark. One-quarter will remain undereducated.

The report also looked at how different student groups would fare under the different additional years of learning scenarios, stating that fewer low-income students, students with special needs, English learners, and students of color would meet the 12th-grade benchmark compared to their more advantaged peers. “These results are consistent with the findings on how COVID affected students differently,” continues CREDO.

But it is worth pointing out that it is less about how COVID affected different students versus how school closures during COVID affected different students. Less in-person instruction has been linked to greater learning loss, and districts with a greater share of students of color were associated with less in-person instruction. Additionally, districts with more low-income children were more likely to continue remotely, despite disadvantaged students being more likely to have difficulty accessing the internet and devices needed for remote learning. Several studies have found that the per-capita rate of COVID-19 cases in an area was not significantly predictive of whether a school district would reopen or not.

While the percentage of students meeting average 12th-grade learning benchmarks are estimates, and theoretical, as “no district in the country is capable of extending the years of schooling they offer by these amounts,” reminds The 74, the bottom line is that even with substantial additional instructional time, the impact of learning loss will persist.

So, what’s the solution?

Not current remedies, writes The 74. High-dosage tutoring, while delivering moderate increases for average learners, does not produce sustained benefits for students with low paces of learning.

Moreover, a large number of studies have found that the benefits from tutoring do not survive into the future for any students. Summer camps offer even less cause for optimism: They provide lower dosages, and for a shorter time.

Instead, schools should consider shifting to a mastery-based approach versus “maintaining the current system of organizing students by grade level,” proposes The 74.

As long as students continue to progress and demonstrate growth, their schooling could continue. High achievers could reach the benchmarks faster than is usually allowed and move on to more advanced goals. Releasing students from the traditional school year would free up resources that could be devoted to helping lower-POL students.

Incentivizing successful and high-impact educators to be deployed in new ways is also worth considering, continues The 74.

Children need higher-quality instruction to realize greater learning gains, and the evidence is clear that the best teachers get better results than average educators. Making sure each classroom has excellent instruction should be the ultimate goal.

…

By utilizing data from professional observations and student test scores, schools could identify the instructors who truly make a difference in their students’ learning and deploy those high-impact teachers in new ways. One approach would be to offer incentives — bonus pay, for example, or credit that could be put toward a sabbatical or other specialized training — to motivate higher-quality teachers to add students to their classes. Offering extra support to teachers who take on extra tasks, such as class aides or release from other duties, could also help. And placing lower-performing students in classes with a high-quality teacher and higher-performing peers can produce a jump in performance.

Even with changes, though, the current system won’t work for all students. By definition, a top-down, one-size-fits-all model of education will always leave students behind. Families must be empowered to access the learning environment that works best for them and their children’s individual needs. Without changes to who can access alternatives to government schools, students will continue to be left behind, and the current system will continue to fail too many of our next generation of leaders.