Evidence suggests that, compared to Wisconsin, Minnesota’s minimum wage hikes have cost restaurant jobs and lowered youth employment

Gophers and Badgers love to compare their states. This has taken on a particular urgency since January 2011, when Mark Dayton became governor in Minnesota and Scott Walker took office across the St Croix. Both have different approaches to economic policy. Any bit of economic data is seized upon as proof that either the ‘socialism’ of Dayton’s Minnesota or the ‘laissez faire’ of Walker’s Wisconsin is delivering better results.

The latest comparison comes from economist Noah Williams at the Center for Research on the Wisconsin Economy at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. In a policy brief titled ‘Evidence on the Effects of Minnesota’s Minimum Wage Increases‘, he looks at how different policies regarding minimum wages in the two states have played out in labor markets. Since 2010, the minimum wage in Wisconsin has held constant at the federal level of $7.25 ph. In Minnesota, it has risen to $9.65. As Williams writes,

before the wage hikes in 2013, 74,000 workers accounting for 4.7% of Minnesota’s hourly workforce earned the minimum wage of $7.25 or less. But after the increase to $9.50 in 2016 this number more than tripled to 248,000, or 15.4%, of Minnesota’s hourly workers. This substantial increase in affected workers was heavily concentrated in the restaurant industry and among the youth demographic…

Looking at each of these demographics in turn, Williams finds that

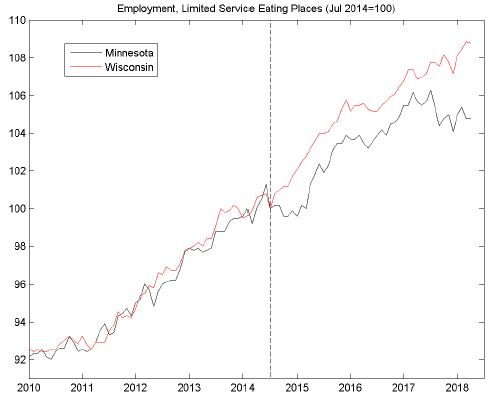

that from the beginning of 2010 until July 2014 fast food restaurant employment in the two states grew at the same rate. However beginning with the first minimum wage hike in Minnesota, there has been a divergence which has grown over time. The employment differences between the states have become especially notable over the past year, as fast food employment in Minnesota stagnated while it has continued to increase in Wisconsin. In total, from July 2014 to May 2018 fast food restaurant employment grew by 4.8% in Minnesota but 8.8% in Wisconsin. While other factors may have played a role, the timing of the trend break suggests that the minimum wage increases in Minnesota accounted for much of this 4 percentage point divergence.

Figure 1 – Limited Service Restaurant Employment, Minnesota and Wisconsin, 2010-2018

Source: Center for Research on the Wisconsin Economy

Turning to youth employment, Williams finds that

in both states the level of youth employment was relatively constant from 2009-2014, with a slight increase in Minnesota and a decline in Wisconsin in the 2012-2014 period. However after Minnesota began its minimum wage increases in 2014 there was a big fall in youth employment in Minnesota, and an increase in Wisconsin over the same period. In particular, youth employment averaged 9% lower, a reduction of 35,000 young workers, in Minnesota in the three years following the minimum wage increases compared to the preceding three years. During the same span, youth employment increased by 10.6%, or 43,000 jobs in Wisconsin. Again, while other factors certainly played a role in driving these changes, the timing of the trend break and the concentration of youth employment in minimum wage jobs suggests that much of it was driven by the minimum wage increases.

It is also important to note that while youth employment fell sharply in Minnesota after the minimum wage increases, youth unemployment was relatively unchanged. In particular, even though youth employment experienced a sharp reduction of 53,000 jobs between 2014 and 2015, the youth unemployment rate fell from 8.1% to 7.6% as an even larger number of 60,000 young workers left the labor force. This suggests that rather than increasing youth unemployment rates, the minimum wage hikes reduced levels of employment, and led the previously employed young workers to leave the labor force.

Figure 2 – Youth Employment, Minnesota and Wisconsin, 2009-2017

Source: Center for Research on the Wisconsin Economy

Williams summarizes his findings, saying that

Overall these results are consistent with a competitive market for low wage workers in Minnesota. The distortions from the minimum wage increases led to higher incomes for some workers, but lower employment particularly among young and low-skilled workers, and higher prices for the products of low-skilled labor.

In terms of a ‘Border Battle’, Minnesota’s minimum wage hikes have raised wages for some workers relative to Wisconsin. But they have also lead to less employment in restaurants and less employment for young workers. As St. Paul considers instituting a $15ph minimum wage, with restaurant workers at the forefront, this should make them think again. A minimum wage of $15ph might work out at $0ph.

John Phelan is an economist at the Center of the American Experiment.