Friction Among Minnesota Greens and Blue Collar Workers Intensifies After PolyMet Delays

On Monday, we got the news that Minnesota Court of Appeals dealt a setback to the proposed PolyMet copper-nickel mine in northern Minnesota by sending two crucial permits, the permit to mine and the dam safety permit, back to the Department of Natural Resources. The ruling, which also stated the agency must hold a contested case hearing, has opened a widened a rift between the environmental wing of liberal interests in Minnesota, and the blue collar workers who traditionally supported liberal lawmakers.

A case in point is this statement from Jason George, who is the Business Manager for the Local 49 Operating Engineers union:

“I am not only extremely disappointed by the Court’s decision, but I am deeply concerned about the uncertainty of our permitting process. The PolyMet project has gone through 15 years of exhaustive study and scrutiny by Minnesota’s state agency experts and met or exceeded every environmental standard in law.

The fact the entire process and all this work can be thrown out today by three judges who spent a few months on this case is alarming. This is a bad decision, but the PolyMet project will go forward. The future of northeastern Minnesota depends on it, and we will never give up on them.”

The lawsuit that prompted this decision was spearheaded by liberal environmental law firms from the Twin Cities metro area. One of groups involved in the lawsuit that prompted this decision is headed by Becky Rom, a wealthy Twin Cities lawyer, who famously derided people who were supportive of more mining in northeastern Minnesota in The New York Times. Rom stated:

“Danny Forsman drivesto the mine in his truck, comes home and watches TV, and he doesn’t know this world exists.”

Later in the article, Reid Carron, Rom’s husband, said one of the most arrogant things he could have possibly said:

“Resentment is the primary driver of the pro-mining crowd here — they are resentful that other people have come here and been successful while they were sitting around waiting for a big mining company,” Carron told me. “They want somebody to just give them a job so they can all drink beer with their buddies and go four-wheeling and snowmobiling with their buddies, not have to think about anything except punching a clock.”

This attitude, which implies that people from Greater Minnesota who support mining are inferior to their more learned “betters” in the Twin Cities is incredibly insulting. These lawyers oppose mining, building new pipelines, and logging, but they all have a cellphone, they drive on roads paved with oil-derived asphalt, and the homes they live in are supported by lumber.

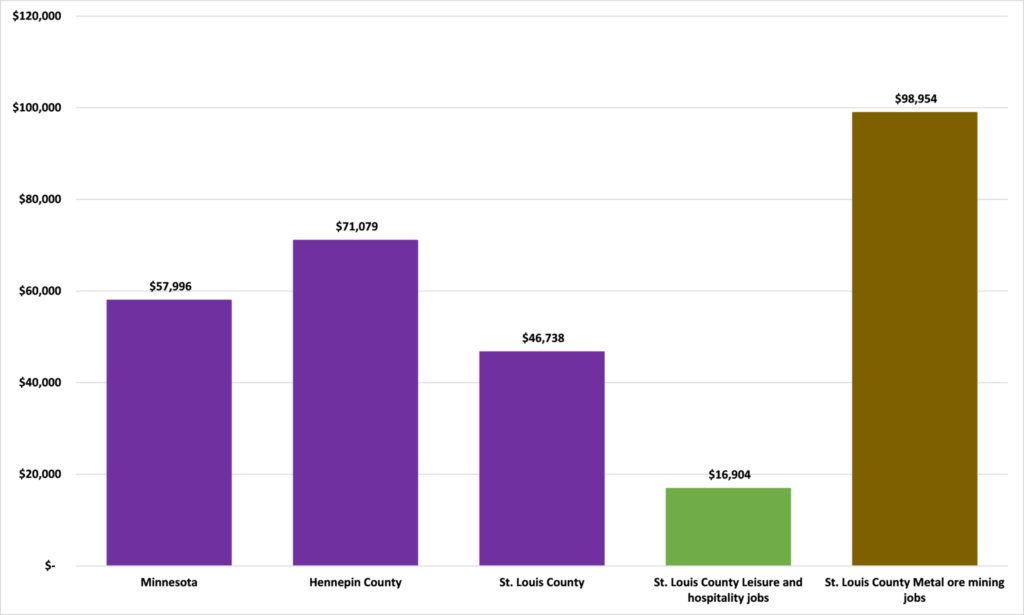

Instead of encouraging high-paying jobs in these industries, Twin Cities environmental lawyers suggest the people of the Iron Range get a job in the tourism industry, even thought this means they would earn almost-poverty level wages for one-person households, and forget trying to raise a family and save for a college fund on these kinds of jobs.

The people of the Iron Range do not live and work at the pleasure of people who live in more densely-populated areas. They do not exist to scoop ice cream on the weekends for people who live in Minneapolis. They are proud people, good people, who are tired of being portrayed as backward, bigoted, or unenlightened.

It is no surprise that the people of the Range feel more alienated by St. Paul than ever.