Growing Minnesota’s economy is the best way to end poverty

Governor Tim Walz wants to end childhood poverty. Citing the significant impact that expanding the federal child tax credit has had on child poverty in the country, Walz touted his support for state spending specifically targeted at ending child poverty in Minnesota

Specifically, Walz wants to build off the “success” of the federal child tax credit:

with a new state refundable tax credit for children younger than 18, providing $1,000 per child to lower income families with less than $50,000 in household income, with a maximum credit of $3,000. The Department of Revenue estimates nearly 364,000 Minnesota filers would benefit from the credit.

But:

Unlike the federal program, the proposed state credit would allow people who make very little or no income to qualify, and it would be available until children hit 18 years old. The state payment would come in one lump sum, unlike the expanded federal credit, which came monthly.

And in addition to creating a child tax credit,

Walz also wants to expand a dependent care tax credit to help families with young children afford child care. Families with one child under 5 years old would receive up to $4,000 per year, while families with three children under 5 could receive up to $10,500. The benefit would phase out between $200,000 and $240,000 in household income.

Does spending more money to reduce poverty work?

During the pandemic, low-income Americans saw massive job losses. This led to income loss and a hike in the poverty rate. But in response to the pandemic, the U.S. government made numerous payments to people.

These included stimulus checks, expanded child tax credit payments, and expanded unemployment benefits. So despite these job losses, poverty as measured by the Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM) — which might be a better representation of poverty, as it accounts for other things that are left out of the official poverty measure, like government assistance, geographic differences, and household size — actually fell.

So technically yes, giving money to people who do not have money, holding all else constant, increases people’s disposable income. This can put them above the poverty level.

However, whether that can be called success is an entirely different matter.

For one, it costs the government a lot of money to keep people out of poverty. During the pandemic, for example, Congress passed three stimulus bills all totaling about $5 trillion to keep Americans and the economy afloat.

In 2020, President Donald Trump signed two bills sending nearly $3 trillion in stimulus for the economy. Then in March 2021, President Joe Biden signed the American Rescue Plan, which gave out another $2 trillion to the US economy and people.

Secondly, government spending comes at a cost to taxpayers and the economy. All the massive spending undertaken by the federal government (plus other factors) has significantly raised inflation, inflicting pain on American households and families. Not to mention that the U.S. budget is currently nearing a fiscal crisis. This is partly because massive spending has increased debt and raised interest expenses. So whether the benefit from such spending was worth the cost is debatable.

Moreover, despite this massive spending, poverty did not fall to zero. Poverty reduction was also temporary. Ending COVID-19 programs has ended with it the progress that the country made in reducing poverty. This is because these payments, like existing welfare programs, were not necessarily intended to get people out (and stay out) of poverty. They existed only to help the poor afford basic necessities while they faced a difficult time.

So in short, while government payments might reduce poverty, they do so at a very high cost to taxpayers and the economy. Additionally, such progress is unsustainable without continuous spending.

But luckily for Minnesota, evidence from prior to the pandemic does show that there is a more efficient and sustainable way to reduce poverty — growing the economy.

Growing the economy is a better way to reduce poverty

The U.S. Census Bureau reported in 2020 that

In 2019, the poverty rate for the United States was 10.5%, the lowest since estimates were first released for 1959.

Poverty rates declined between 2018 and 2019 for all major race and Hispanic origin groups.

Two of these groups, Blacks and Hispanics, reached historic lows in their poverty rates in 2019. The poverty rate for Blacks was 18.8%; for Hispanics, it was 15.7%.

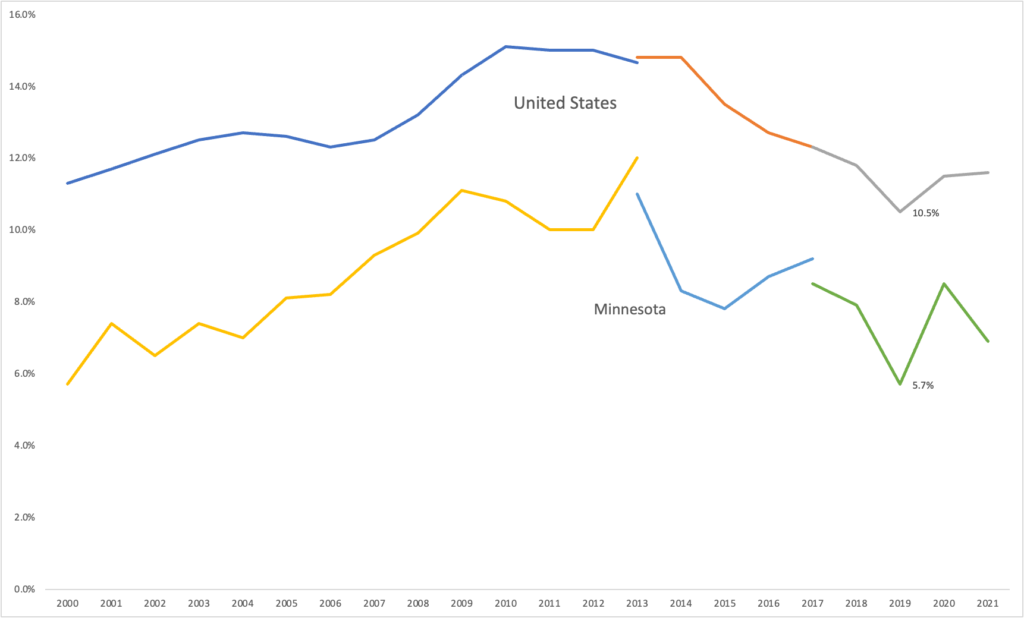

Compared to the U.S., Minnesota has a lower official poverty rate. And in 2019, that rate fell even further, reaching 5.7 percent, down from 7.9 percent in 2018.

Generally, for both the U.S. and Minnesota, poverty rose in the years leading to the Great Recession of 2007-2009. In the U.S., poverty peaked in 2011, reaching 15.1 percent. In Minnesota, poverty peaked in 2013, reaching 12 percent.

And while poverty was somewhat on a decline — albeit inconsistently — since the end of the Great Recession, it did not reach its lowest historical levels until 2019. In 2019, the U.S. experienced its lowest official poverty rate since 1959. Minnesota reached its lowest level before the recession — 5.7 percent.

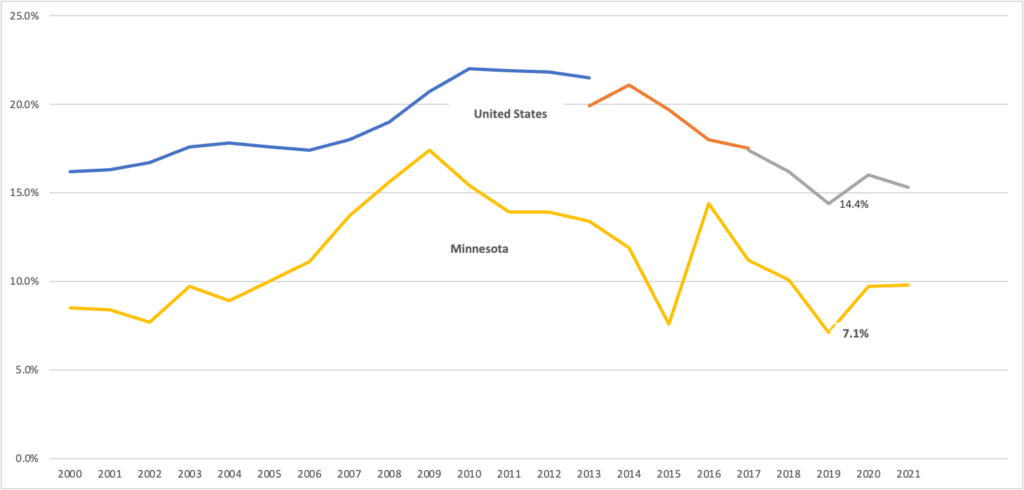

The same was true for child poverty. For the United States and Minnesota, official child poverty rates reached historic lows in 2019 at 14.4 percent and 7.1 percent, respectively.

Figure 1: Official poverty rate, 2000 to 2021

Note *: The U.S. Census Bureau redesigned its survey in 2013 and also updated its processing system in 2017. For those two years, the Bureau provided two figures for poverty rates for each year — as demonstrated in the figure above.

Figure 2: Child poverty rates, 2000 to 2021

Note*: The U.S. Census Bureau redesigned its survey in 2013 and also updated its processing system in 2017. For those two years, the Bureau provided two figures for poverty rates for each year —as demonstrated in the figure above for the United States.

Poverty trended down in 2019 even if we use the SPM. While the SPM was at its lowest in 2021, due to government payments, much like the official poverty rate, it also went down significantly prior to the pandemic. Between 2018 and 2019, for example, the U.S. SPM rate went down from 12.8 percent to 11.8 percent.

How did this come about?

The simple answer is economic growth.

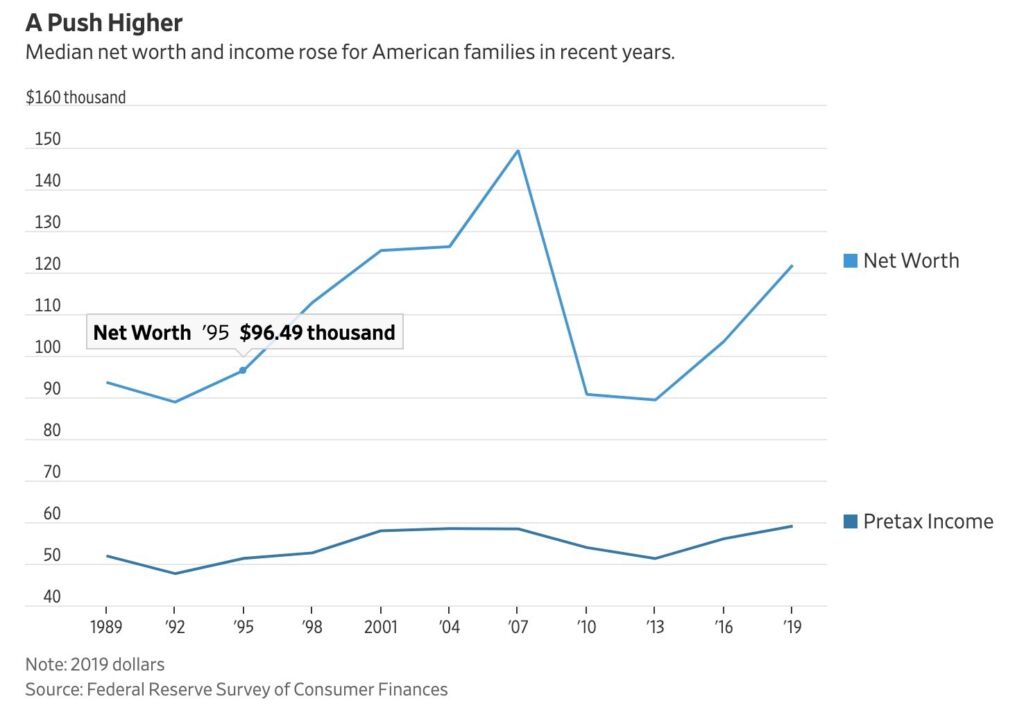

In the few years prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. economy grew at a higher rate than previously. For that reason, incomes among Americans also grew. According to data from the Federal Reserve Survey of Consumers, between 2016 and 2019, median incomes grew 5 percent as the economy grew at 2.5 percent per year, on average. During the same period, unemployment fell.

End result? Poverty fell to record lows, without the government having to spend trillions of dollars on assistance programs and payments.

To sustainably end poverty, Walz should focus on policies that grow the economy instead

It is hard to say where the country would be if COVID-19 did not happen. The possibilities are endless.

That, however, does not take from the fact that a growing economy reduces poverty and does so more efficiently, and sustainably.

On the other hand, relying on government spending to reduce poverty necessitates more government spending, especially during times of economic turmoil when tax revenues are even more likely to be down. Even then, government spending does not completely eliminate poverty or even reduce it. California, for example, has higher than average poverty despite having one of the country’s most progressive welfare systems.

So, if Walz is serious about ending poverty — that is helping people get out and stay out of poverty — he needs to support and advocate for policies that grow the economy. A growing economy creates more jobs, giving people the opportunity to earn income and climb the economic ladder. This in turns lessens the pressure on the state government due to the reduced need for welfare spending, while at the same time increasing tax revenues.