What’s missing from the debt ceiling talks and why you should be worried

As soon as June 1, the U.S. government could run out of money to pay its bills. This means that without further borrowing, the U.S. government would not be able to fund ongoing obligations, including interest on debt, forcing a default.

The government cannot borrow more money, however, because it has reached its limit. President Joe Biden and Democrats want Congress to take a stand-alone vote to raise the debt ceiling. But the Republican-led House passed a bill — called the Limit, Save, Grow Act — which would require raising the debt limit to be accompanied by spending restraints.

Last Tuesday, President Joe Biden met with House Speaker Kevin McCarthy to talk about potentially raising the debt ceiling. And according to news reports, the two will be meeting again today to continue such talks. Unfortunately, that is not the comforting news that it should be.

The U.S. debt currently stands at over $31 trillion — about $95,000 per person in the U.S. It is clear that whatever the result, it would have a far-reaching impact both on the economy and the country’s fiscal health. Yet despite the magnitude of the problem, our politicians don’t seem to treat this as a warning sign to take action and address high and growing debt, and more specifically what’s driving that debt — growth in entitlement spending. Something important is missing from the debt ceiling discussion, and that could affect you and the future of the economy deeply.

What is the debt ceiling?

As the U.S. Department of the Treasury defines it, the debt limit:

is the total amount of money that the United States government is authorized to borrow to meet its existing legal obligations, including Social Security and Medicare benefits, military salaries, interest on the national debt, tax refunds, and other payments.

Before 1917, Congress had to authorize every single issue of bonds by the Treasury. But in order to make it easier to sell bonds to finance World War I, congress passed the debt limit, meaning the Treasury could issue bonds without getting approval from Congress every single time, as long as it did not reach the debt limit.

Looking at history, it’s highly unlikely that the U.S. could default on its debt. The U.S. debt limit has been raised numerous times to accommodate spending deficits in the past. According to the Treasury,

Since 1960, Congress has acted 78 separate times to permanently raise, temporarily extend, or revise the definition of the debt limit

But in the event that a default happened, it could spell catastrophic results not only for the U.S. economy, but for the globe, especially when we consider the size of the debt, and our country’s standing in the global economy. Currently, U.S. Treasury bonds are viewed as one of the safest investments, giving us an AAA rating, which enables the U.S. government to borrow at low-interest rates. A default would mean a downgrade and therefore higher borrowing costs.

Interest payments already make up a significant portion of federal spending and are expected to grow even more. According to projections from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), annual interest payments are estimated to climb to $745 billion by 2024, reaching $1.4 trillion by 2033. As a proportion of the economy, interest payments are expected to grow from 2.7 percent of GDP in 2024 to 3.7 percent in 2033. In 2024, spending on interest payments will surpass spending on major healthcare programs, apart from Medicare.

Because the U.S. government acts as a benchmark for borrowing costs, a default would also raise interest rates for the rest of the economy, and the rest of the globe. This would mean less capital, investment, less production, and thereby slow economic growth or even decline. Combine an already-slowing economy with a default and there is no telling the level of impact a default would have.

Current US Debt

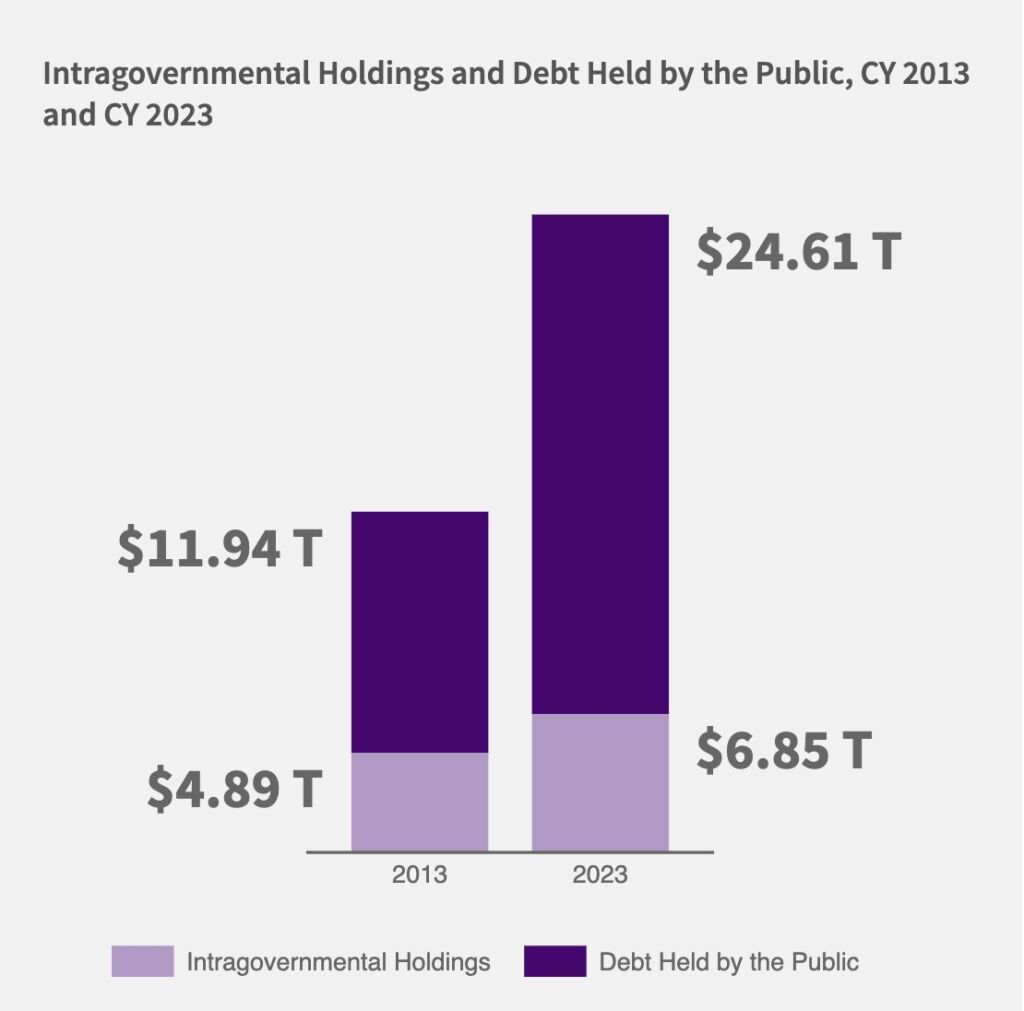

If default isn’t an option, the U.S. government is left with just one other choice — at least in the short term — which is raising the debt limit to borrow more. But currently, the U.S. national debt stands at over $31 trillion and is expected to grow. Taking out debt held by state and local governments, debt held by the public stands at $24.61 trillion.

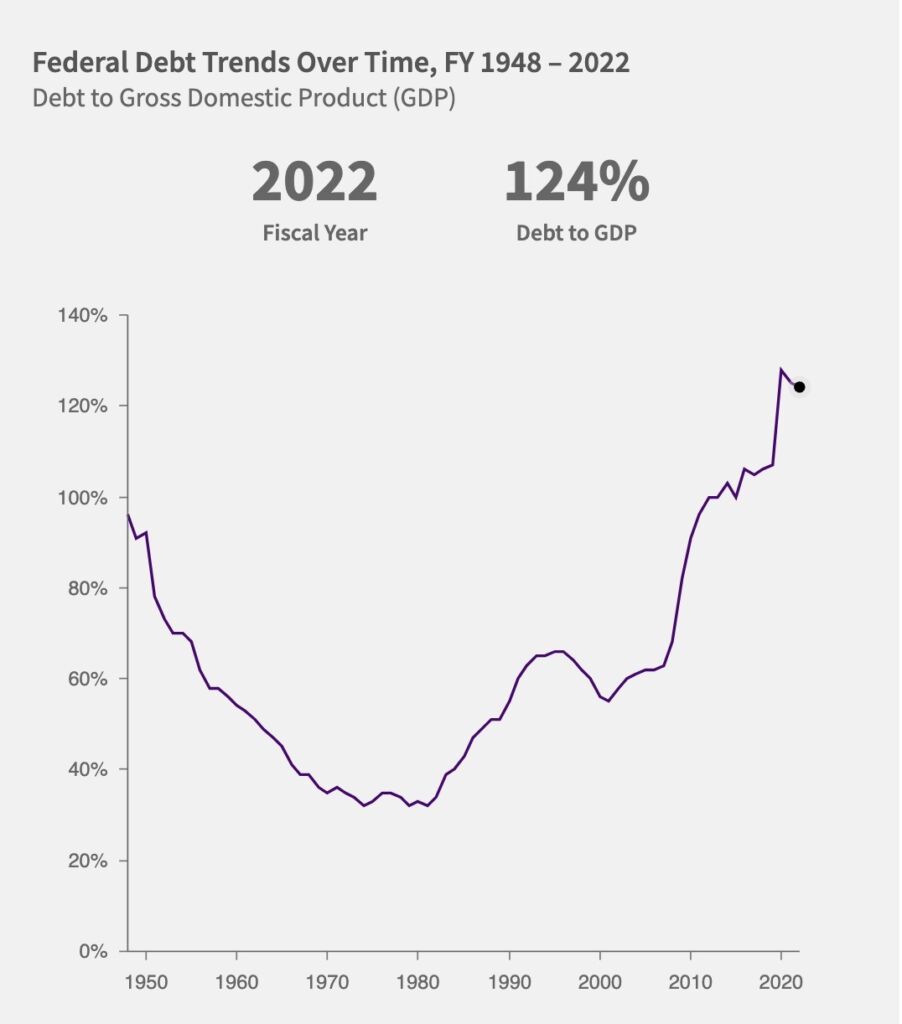

As a proportion of GDP, total debt stood at 124 percent of GDP in 2022. In the period between 1948 and 1981, debt as a ratio to GDP consistently declined, going from 96 percent of GDP to 32 percent of GDP. However, beginning in 1982, it started rising, reaching 124 percent in 2022.

What’s even more concerning,

An incredible 70 percent of that $31 trillion debt load was accumulated from the start of fiscal year (FY) 2008 (October 1, 2007) through FY 2022 (September 30, 2022), a period of just 15 years.

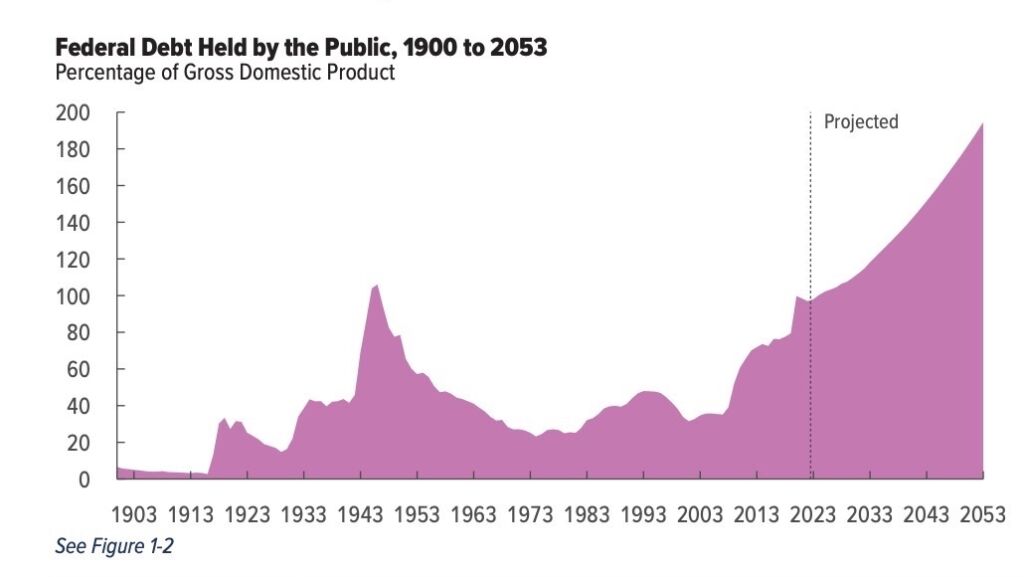

In a report published in February this year, the CBO estimated that debt held by the public will double by 2033, and reach nearly 200 percent of GDP in 30 years. That is even after assuming low interest rates, a growing economy, no major disruptions — like COVID-19 — and no new major spending. According to the CBO, the growing debt is mainly due to growing spending on two entitlement programs — Medicare and Social Security — as well as growing interest payments.

To say the least, the U.S. debt situation is in bad shape and expected to get even worse if no action is taken.

High and increasing debt means high borrowing costs, not only for the federal government but also for the private sector. As interest rates rise, it means more money going to servicing debt, and not essential government services, like infrastructure. That’s not all, however.

As I previously wrote,

For every $1 that the U.S. government borrows, there is $1 less capital available for businesses and other private sector entities..

So, in addition to high-interest payments, increasing government debt will crowd out the private sector, resulting in lower private-sector investment, thereby slowing economic growth in years to come. Not to mention that increasing debt will mean the US government has less flexibility to respond to future crises.

What Republicans are proposing

On April 26, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the Limit, Save, Grow Act. The bill, which raises the debt ceiling, includes provisions to limit the growth of spending. Specifically, the bill would:

suspend the debt ceiling through either March 31, 2024 or a $1.5 trillion increase from the current $31.4 trillion ceiling – whichever comes first.

But in addition to raising the debt ceiling, the bill would also:

return total discretionary spending to the Fiscal Year (FY) 2022 level in FY 2024 and cap annual growth at 1 percent for a decade thereafter; rescind unspent COVID relief funds; repeal most of the Inflation Reduction Act’s (IRA) energy and climate tax credit expansions; rescind the IRA’s increased Internal Revenue Service (IRS) funding; make changes to energy, regulatory, and permitting policies; impose or expand work requirements in several federal safety net programs; and prevent implementation of President Biden’s student debt cancellation and Income-Driven Repayment.

The CBO estimated that in total, the bill would reduce deficits by $4.8 trillion in the next decade. The majority of that reduction in the deficit — $3.2 trillion — would come from changes in discretionary spending. Mandatory spending — which makes up the majority of government spending and is expected to grow even further — will only be $0.7 trillion lower if the law is passed.

What’s missing

The fact of the matter is that the federal government — and consequently the entire nation — is between a rock and a hard place. On one hand, defaulting on the debt would spell catastrophe for the U.S. economy and beyond. On the other hand, continuous borrowing will raise our debt, which is already at a concerning size and is estimated to grow significantly in the next decade.

Unfortunately for the rest of the country, Congress is not even trying to tackle skyrocketing debt levels or what’s causing it. President Biden and Democrats have given every indication that they are unwilling to consider any spending cuts. While Republicans have passed a bill that will stall growth in government spending, it does nothing to address entitlement spending — which will be the main driving factor of growing debt in the next decade.

Given our history, it’s highly unlikely that the U.S. would default. But that again only leaves more borrowing as the more likely solution to the impending crisis. Americans should be concerned that while legislators should treat this as a wake-up call and come up with a solution that sustainably addresses the national debt, no such action is likely going to be taken.

There is certainly a conversation to be had about the debt crisis. But if that conversation does not include addressing growing entitlement spending, then anything else will only make a small dent in America’s debt crisis.