Less policing means more crime in Minneapolis

Violent crime in Minneapolis is up 19 percent so far in 2021. Why is this happening? One part of the answer is less policing in the city.

Economists Tanaya Devi and Roland G. Fryer Jr released a paper last year which provided “the first empirical examination of the impact of federal and state “Pattern-or-Practice” investigations on crime and policing” and found that:

For investigations that were not preceded by “viral” incidents of deadly force, investigations, on average, led to a statistically significant reduction in homicides and total crime.

And the bad news for Minneapolis:

In stark contrast, all investigations that were preceded by “viral” incidents of deadly force have led to a large and statistically significant increase in homicides and total crime. We estimate that these investigations caused almost 900 excess homicides and almost 34,000 excess felonies.

Why?

The leading hypothesis for why these investigations increase homicides and total crime is an abrupt change in the quantity of policing activity. In Chicago, the number of police-civilian interactions decreased by almost 90% in the month after the investigation was announced. In Riverside CA, interactions decreased 54%. In St. Louis, self-initiated police activities declined by 46%. Other theories we test such as changes in community trust or the aggressiveness of consent decrees associated with investigations — all contradict the data in important ways.

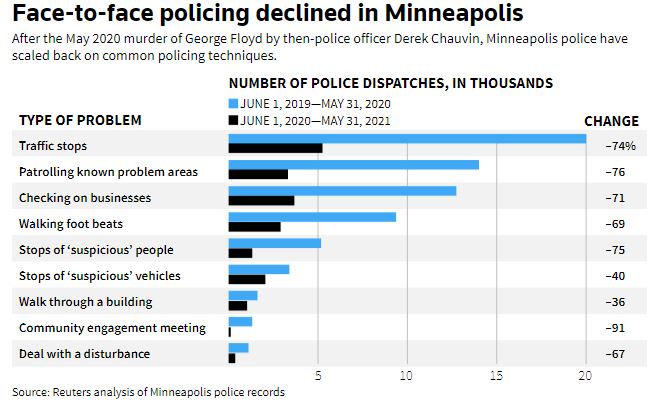

It seems that the quantity of policing has fallen dramatically in Minneapolis, too. This week, Reuters reports:

Minneapolis’ police officers imposed abrupt changes of their own, adopting what amounts to a hands-off approach to everyday lawbreaking in a city where killings have surged to a level not seen in decades.

Almost immediately after Floyd’s death, Reuters found, police officers all but stopped making traffic stops. They approached fewer people they considered suspicious and noticed fewer people who were intoxicated, fighting or involved with drugs, records show. Some in the city, including police officers themselves, say the men and women in blue stepped back after Floyd’s death for fear that any encounter could become the next flashpoint.

“There isn’t a huge appetite for aggressive police work out there, and the risk/reward, certainly, we’re there and we’re sworn to protect and serve, but you also have to protect yourself and your family,” said Scott Gerlicher, a Minneapolis police commander who retired this year. “Nobody in the job or working on the job can blame those officers for being less aggressive.”

In the year after Floyd’s death on May 25, 2020, the number of people approached on the street by officers who considered them suspicious dropped by 76%, Reuters found after analyzing more than 2.2 million police dispatches in the city. Officers stopped 85% fewer cars for traffic violations. As they stopped fewer people, they found and seized fewer illegal guns.

…

To measure the change in policing, Reuters examined millions of dispatch and crime records from the city’s police force that track how officers spend their time. The pattern was stark: Within days of Floyd’s death, the number of stops and other encounters initiated by city patrolmen plunged to their lowest point in years.

Elder, the police spokesman, said the change should be unsurprising at a time when the department was overwhelmed by rioting.

But records show the pullback continued long after the unrest ended. In May, the most recent month for which complete records were available, officers initiated about 58% fewer encounters than they did in the same month the year before.

The number of traffic stops they conducted was down 85% over the same period. Business checks — in which officers stop at a business to talk to employees and customers — were down 76%. The number of people the police stopped for acting suspiciously also dropped 76%.

Fewer stops led to fewer people being searched for guns or drugs. The month before Floyd was killed, police made 90 drug arrests, police records show. A year later, they made 28. The number of people charged with breaking gun laws dropped by more than half, even as shootings multiplied.

Some of this decline in the quantity of policing in Minneapolis is down to a decline in the quantity of police. Reuters notes that:

Between retirements and a surge of officers taking medical leaves, the city had 200 fewer officers to put on the streets this year than it did in 2019, a drop of about 22%.

But that doesn’t account for all of it:

Nonetheless, Reuters found, the drop in police-initiated interactions was steeper and more sudden than the drop in the number of officers. By July 2020, the number of encounters begun by officers had dropped 70% from the year before; the number of stops fell 76%.

It isn’t hard to see why police officers would be wary of initiating contacts when figures such as Minneapolis City Council President Lisa Bender are spreading lies about them.

This post is heavy on numbers, but I’m an economist, after all. Tomorrow, we’ll look at some of the human stories behind those numbers.