Literacy gains more likely when students learn more social studies

Elementary literacy skills are pivotal for any student’s educational trajectory. Without a strong foundation of these skills in the early years, a student’s learning and progress in middle and high school can be greatly set back. Based on assessment scores, improving the reading ability of elementary students needs to become an urgent priority.

But wait, you say, literacy has been a priority. More elementary class time is devoted to English language arts (ELA) instruction than any other subject.

Well, it doesn’t appear to be working, though the extra time is likely well intentioned.

What is associated with improved reading ability? Increased instructional time in social studies—not ELA. According to a new report by the Thomas Fordham Institute’s Adam Tyner and Sarah Kabourek, focusing on academic content versus generalized reading skills and strategies will equip students with the background they need to comprehend a variety of texts and develop true literacy. Tyner and Kabourek used data that samples over 18,000 students’ classroom experiences and reading development over a six-year period (kindergarten through fifth grade), which helps gauge the role accumulation of knowledge plays in reading improvement.

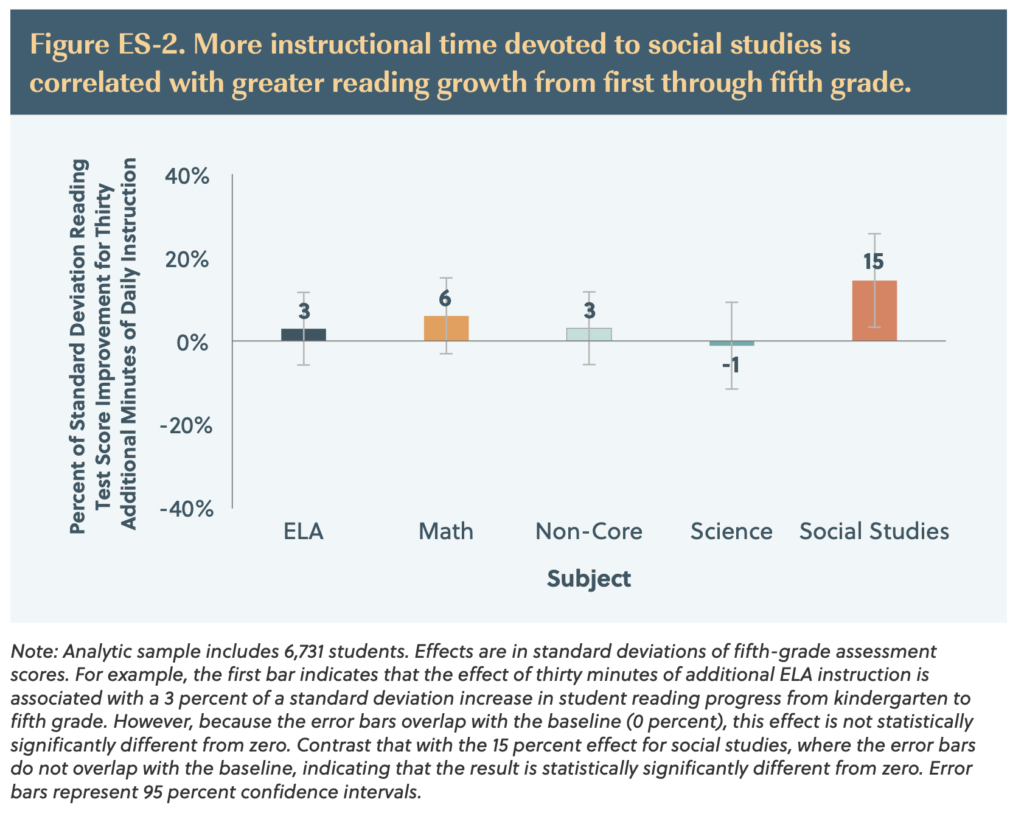

Social studies is the only subject with a clear, positive, and statistically significant effect on reading improvement. On average, students who receive an additional thirty minutes of social studies instruction per day (roughly equivalent to moving from the tenth to the ninetieth percentile of social studies instructional time) in grades 1–5 outperform students with less social studies time by 15 percent of a standard deviation on the fifth-grade reading assessment, even after controlling for multiple measures of kindergarten reading ability and a host of student, school, and teacher factors.

While additional social studies time is linked to reading improvement regardless of students’ home language, the effect is stronger for students in non-English-speaking homes, Tyner and Kabourek continue.

Students from homes in which English is not the primary language see larger effects from social studies instructional time than do students from homes where it is. For students from non-English-speaking homes, an additional 30 minutes of social studies time per day during elementary school corresponds to about a quarter of a standard deviation increase in reading ability. For students from primarily English-speaking families, that same 30 additional minutes corresponds to an improvement in reading of about 12 percent of a standard deviation (statistically significant only at the 90 percent confidence level).

Female students and students from lower-income homes also benefit the most from additional social studies time.

Effects are consistently positive for students in the bottom three SES quartiles but nearly zero and statistically insignificant for students in the wealthiest quartile. More specifically, students in the bottom three quartiles have similar positive effects from an additional 30 minutes of daily social studies instruction during elementary school, corresponding to greater reading development between 17 and 21 percent of a standard deviation.

Tyner and Kabourek conclude that because “students are not getting additional benefit from lengthy periods of ELA instruction,” elementary schools “should make more room for high-quality social studies instruction.”

The link between social studies and reading may stem from the way that social studies instruction can help build systematic knowledge and vocabulary in multiple domains, which are broadly applicable and transferable to other topics. Social studies can help students understand history, current events, family and social relationships, and common narratives; whereas, reading passages that putatively cover other subjects, such as literature or drama, may assume the reader already has a grasp of such knowledge.

Regardless of how much, or if at all, literacy class time gets tweaked, building knowledge through content-rich texts and topics would still help transform the reading block, the authors add on. By teaching knowledge-rich content in the classroom, which more affluent and white students often have greater access to outside of the classroom, teachers can help all students develop better literacy outcomes. As E.D. Hirsch has recently stated, instruction is a waste of time in the absence of specific knowledge.