1st Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment at Gettysburg

The true, seldom told story of overwhelming sacrifice and heroism.

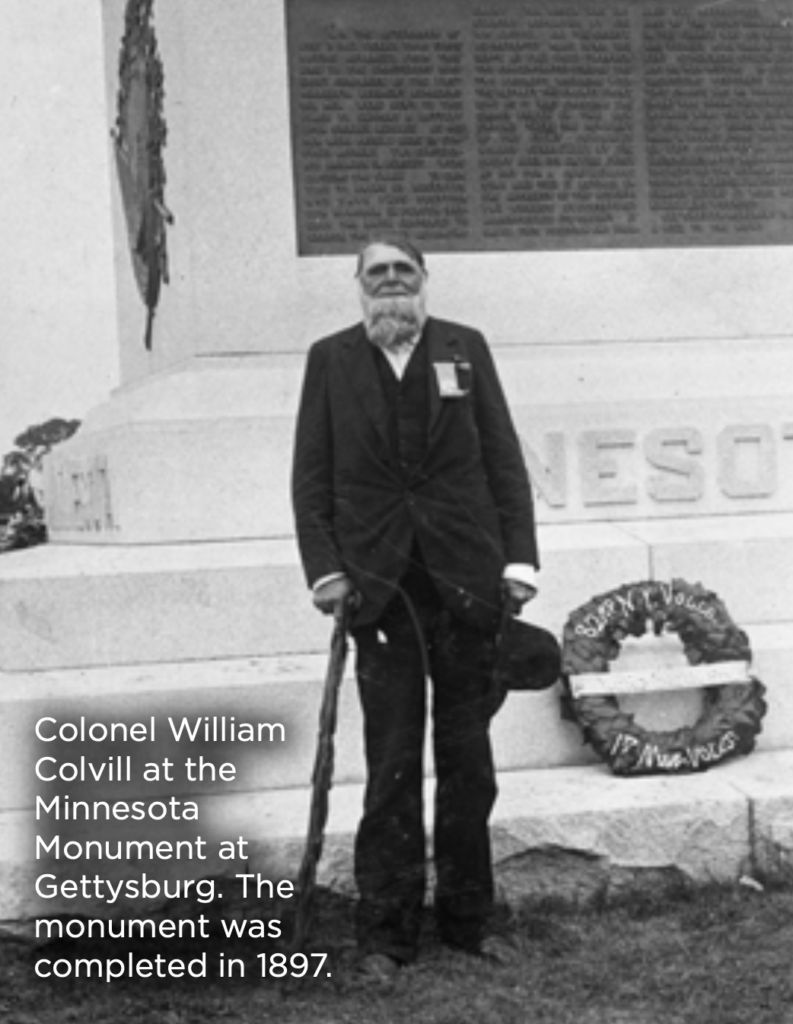

In June 1905, William J. Colvill traveled to the Soldiers Home in Minneapolis to attend a reunion of the veterans of the 1st Minnesota Volunteer Infantry regiment. He walked with a cane, a visible sign of the wounds which had plagued him for 42 years, since the evening of July 2, 1863. That was the day the 1st Minnesota saved the Union but was destroyed in the process.

From the Headwaters of Minnesota

When the Confederates fired on Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861 opening the Civil War, Minnesota’s governor, Alexander Ramsey, was in Washington, D.C. Two days later, he went to the Secretary of War and offered 1,000 soldiers from Minnesota, the first state to do so. The following day, President Lincoln declared the secessionist states to be in unlawful rebellion, leaving him “no choice…but to call out the war power of the Government.” He asked the remaining states to put 75,000 of their militia at his disposal “to maintain the honor, the integrity, and the existence of our National Union, and the perpetuity of popular government.”

Minnesotans responded enthusiastically. “War meetings were called in various towns,” historian Theodore C. Blegen wrote: “Citizens voiced loyalty and pledged service. Recruiting offices were set up. Enlistments were encouraged, with preference given to members of the volunteer militia companies that supposedly had already been organized.” “In Winona, for example,” wrote historian Richard Moe, “so many of the town’s citizens attended the public meeting that the hall couldn’t accommodate them all.”

Josias Redgate King, a native Virginian who enlisted in St. Paul on April 15, claimed to be the first Union volunteer in the country. At Red Wing, Edward Welch and Covill, an attorney and newspaper publisher originally from New York, literally raced to be the first to sign up, Colvill winning when Welch fell over a chair. In Winona, 15 year old Charley Goddard lied about his age.

The volunteers reflected the young state’s population, all coming either from elsewhere in the United States or abroad. Matthew Marvin had moved to Winona from New York in 1859 to work as a clerk in a leather store. Patrick Henry Taylor, a Little Falls school teacher, was originally from Massachusetts. His brother, Isaac, came from Illinois to assume Patrick’s teaching duties but he, too, soon enlisted. William Lochren was born in County Tyrone in Ireland. All came, as one explained, to fight for “the only flag worth dying for.”

Once mustered, the companies traveled to Fort Snelling. When the recruits arrived from Goodhue County, the St. Paul Press reported:

…an immense crowd of citizens were at the levee to welcome their arrival, and as the companies filed through the streets to their quarters, the sidewalks were lined with ladies and gentlemen, who kept up a continuous cheer as the brave volunteers passed along. The ranks returned the salutations with hearty goodwill.

On April 30, Colonel Willis A. Gorman, former governor of Minnesota Territory and veteran of the Mexican war, informed Ramsey that “the First Regiment of Minnesota Volunteers has been duly mustered into service of the United States, and are now ready for duty, and await the orders of the Secretary of War.”

As they waited, Gorman drilled the men ceaselessly. One recorded: “Morning gun was fired at 5 ½ o’clock. Drill for an hour. Breakfast. Recreation for half an hour. Drill for five hours. Dinner. Recreation. Drill again until five o’clock, when the boys were ‘let out to play.’”

There were distractions. Visitors were frequent. On May 21, the regiment was banqueted on Nicollet Island by the ladies of St. Anthony and Minneapolis, after which, Thomas Pressnell wrote, they were paraded “principally for the purpose of showing us off to the ladies.”

When the orders came, Ramsey took them to the Fort personally and noted how the men “rushed around, hurrahing and hugging each other, as wild as a crowd of school-boys at the announcement of vacation.” On June 22 the regiment left for Washington. They boarded boats in St. Paul where the streets were “thronged by a sympathetic and enthusiastic multitude,” and as they passed levees at a string of river towns, crowds gathered to cheer them on.

On to Bull Run and Gettysburg

In July, the Union army under General Irvin McDowell moved to take the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia. They lumbered into the Confederates at Bull Run on the 21st where, after a chaotic fight, McDowell’s army broke and fled for Washington.

The 1st Minnesota was one of the few Union regiments to emerge from this debacle with its reputation enhanced. An officer reported:

The First Minnesota Regiment moved from its position on the left of the field to the support of Ricketts’ battery, and gallantly engaged the enemy at that point. It was so near the enemy’s lines that friends and foes were for a time confounded. The regiment behaved exceedingly well, and finally retired from the field in good order. The other two regiments of the brigade retired in confusion, and no efforts of myself or staff were successful in rallying them.

The cost was high; the regiment lost more than 20 percent of its strength, proportionately the heaviest Union loss of any in action that day.

Bull Run dispelled the notion of a short war. McDowell’s replacement, George B. McClellan, ably reorganized the Union forces into the Army of the Potomac, but results on the battlefield did not improve. The 1st took part in an attempt to take Richmond from the rear — the Peninsula Campaign — between March and July 1862, which was thwarted by Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Lee sought to capitalize on his victory at Second Bull Run in August by invading the north. He was stopped at Antietam on September 17, the bloodiest day in American history: by nightfall 26,134 were dead, wounded, or missing. The 1st again gained respect. Their brigade commander, Brigadier General Willis A. Gorman noted, “The First Minnesota Regiment fired with so much coolness and accuracy that they brought down [three times one] of the enemy’s flags, and finally cut the flag-staff in two.” But, again, they lost heavily: 28 percent of all men who engaged.

Gettysburg

Lincoln used the occasion of this “victory” to issue his Emancipation Proclamation, freeing all slaves in states then in rebellion against the federal government, but this brought no immediate military benefit. Lee defeated McClellan’s replacement, Ambrose Burnside, at Fredericksburg in December. In May 1863, he defeated Burnside’s replacement, Joseph Hooker, at Chancellorsville. Lee again sought to capitalize by invading the north, slipping past the Army of the Potomac in June. Hooker went in pursuit but was replaced on the way by George Meade.

The two armies collided at Gettysburg on July 1. That first day, despite stubborn Union resistance, the Confederates captured the town but failed to press their advantage. This allowed Meade to take up a strong defensive position to the south, with its right (north) flank on Culp’s Hill, its center running south along Cemetery Ridge, and its left (south) resting on a hill called Little Round Top.

The 1st, part of Winfield Scott Hancock’s II Corps and now led by the popular Colvill, arrived late that day. “We talked a few moments of the great battle that we expected in the morn,” Henry Taylor recalled. The men were confident they “could whip Lee if our forces were well handled, and our troops would fight.” Hancock’s corps was to hold the Union center with Sickles’ III Corps to its left holding the southern flank. The 1st moved into position at about 5:45 am on July 2, staying in reserve while the rest of the Corps took up position on Cemetery Ridge.

For the second day of the battle, Lee planned to attack the Union’s left and roll the line up from the south. But confusion in Confederate ranks delayed the start of the attack. “We lay quietly in a slight hollow,” Lochren wrote, “fairly secure from the enemy’s shells, which came over us occasionally, killing one of our men and wounding another; and although there were some collisions of infantry in establishing positions, there was no protracted fighting during the afternoon.”

Through this delay Sickles brooded. At 2 pm, thinking better ground lay ahead, he advanced his corps without orders. Now separated, in a salient, from the rest of Meade’s line, III Corps was squarely in the path of the Confederate assault when it finally hit around 4 pm.

Seeing the danger, the 1st “were sent to the centre of the line just vacated by Sickles’ advance,” Lochren recalled, “No other troops were then near us, and we stood by this battery, in full view of Sickles’ battle in the peach orchard half a mile to the front, and witnessed with eager anxiety the varying fortunes of that sanguinary conflict.”

Sickles’ troops eventually fell back, “broken and in utter disorder, rushing down the slope” Lochren wrote, “Here was no organized force near to oppose them, except our handful of two hundred and sixty-two men.”

In desperation, Hancock galloped to Colvill and asked: “What regiment is this?”

“First Minnesota,” Colvill answered. “Colonel, do you see those colors?” Hancock asked, indicating the advancing Confederates. Colvill did, and Hancock ordered: “Then take them!”

The 1st were now some of the world’s most experienced soldiers: they knew the fate that awaited them. “Every man realized in an instant what that order meant — death or wounds to us all, the sacrifice of the regiment, to gain a few minutes’ time and save the position,” Lochren remembered, “And every man saw and accepted the necessity for the sacrifice.”

He recalled:

…in a moment…the regiment, in perfect line, with arms, at “right shoulder, shift,” was sweeping down the slope directly upon the enemy’s centre. No hesitation, no stopping to fire, though the men fell fast at every stride before the concentrated fire of the whole Confederate force, directed upon us as soon as the movement was observed. Silently, without orders, and almost from the start, “double- quick” had changed to utmost speed, for in utmost speed lay the only hope that any of us could pass through that storm of lead and strike the enemy. “Charge!” shouted Colvill as we neared the first line, and with leveled bayonets, at full speed, we rushed upon it, fortunately, as it was slightly disordered in crossing a dry brook. The men were never made who will stand against leveled bayonets coming with such momentum and evident desperation. The first line broke in our front as we reached it, and rushed back through the second line, stopping the whole advance. We then poured in our first fire, and availing ourselves of such shelter as the low bank of the dry brook afforded, held the entire force at bay for a considerable time, and until our reserves appeared on the ridge we had left. Had the enemy rallied quickly to a countercharge, its overwhelming numbers would have crushed us in a moment, and we would have effected but a slight pause in its advance. But the ferocity of our onset seemed to paralyze them for a time, and though they poured in a terrible and continuous fire from the front and enveloping flanks, they kept at a respectful distance from our bayonets, until, before the added fire of our fresh reserves, they began to retire and we were ordered back.

“The bloody field was in our possession,” Alfred Carpenter wrote, “but at what cost! The ground was strewed with dead and dying, whose groans and prayers and cries for help and water rent the air.” Colvill was hit in the back and leg; Goddard in the leg and shoulder. Marvin, his foot shattered, fainted twice crawling back to the Union lines. Among the dead was Isaac Taylor, “A shell struck him on the top of his head and passed out through his back, cutting his belt in two,” his brother wrote,

[We] buried him at 10 o’clock am, 350 paces west of a road which passes north and south by the house of Jacob Hummelbaugh and John Swisher (colored) and equi-distant from each, and by a stone wall where he fell, about a mile south of Gettysburg. I placed a board at his head on which I inscribed:

No useless coffin enclosed his breast, Nor in sheet nor in shroud we bound him, But he lay like a warrior taking his rest, With his shelter tent around him.

At twilight, just 47 men answered the regimental roll call. Of the 262 Minnesotans who charged the Confederates, 215 — 82 percent — were killed or wounded, the most severe losses suffered by a Union regiment in a single engagement during the Civil War. Some died later. Goddard, 15 on enlistment, died of complications from his wounds at 23. Colvill died in his sleep in 1905, the evening before the reunion, surrounded by his men.

“The superb gallantry of those men saved our line from being broken,” Hancock reported, “No soldiers, on any field, in this or any other country, ever displayed grander heroism.” The regiment suffered a further 55 casualties the following day repulsing Pickett’s Charge, Lee’s last, desperate gamble, where Private Marshall Sherman captured the flag of the 28th Virginia and won the Medal of Honor. With that, the Confederacy lost the battle and, eventually, the war.

In 1864 their original three-year terms of enlistment expired, and the 1st Minnesota’s service came to an end. Some reenlisted, like Sherman who lost his leg the following year. In terms of percentage of total enrollment killed, it ranked 23rd out of 2,047 Union regiments.

Records show that 21,982 Minnesotans enlisted in the United States’ armed forces between 1861 and 1865. 635 of these died in combat and 1,936 as a result of disease or accident, equal, proportionately, to 86,000 dead from today’s population. Minnesota paid a high price in blood to save the Union and end the evil of slavery.