A republic if you can keep it

The Center’s Martha Njolomole on why Americans should never take ‘The Dream’ for granted.

I was born 27 years ago in Malawi, a small, landlocked country in southeast Africa. My family was poor, but that wasn’t unusual: most people in Malawi are poor. In our home we did not have electricity or running water. We cooked over an open fire, using either firewood or burnt charcoal. Every day, my sister and I walked, sometimes for miles, with buckets to get water, carrying the water back home on our heads. That was drinking and cooking water; we washed our clothes in a nearby river.

Often, we did not have enough to eat and it was not uncommon for us to go to bed hungry. The farm we relied on for food was small. It did not produce enough maize for the whole year, and my family could not consistently afford to buy food.

Health care was not readily available. The closest public health center was a 40-minute walk from our house. (Of course, we didn’t own a vehicle.) On the few occasions when I had to go there, I was never given a medical test or saw an actual doctor. This is because the clinic had no equipment and was understaffed. The nearest hospital was more than an hour away on foot and was plagued by the same issues. The times when I walked there to see a relative who was admitted for an overnight stay, the hospital rooms were overflowing, with people sleeping on the floor and even in the hallways.

The closest primary school I attended was more than two miles from my house, a 45-minute walk. When I started school in January 2002, there were around 150 students in every first-grade classroom. For five of the seven years I attended school, we sat on the classroom floor because the school only had enough desks and chairs for the two upper grades (I skipped fourth grade, otherwise it would have been six years of sitting on the floor). My entire fifth grade was spent learning outside under a tree because there weren’t enough classrooms for the thousands of students in the school. And even though over 1,000 students started first grade with me in 2002, fewer than 400 were able to reach eighth grade, the final year of primary school in Malawi. The rest had dropped out along the way or were repeating earlier grades, still the plight of most Malawian students today.

I loved to read, but my family didn’t have any books. So I looked for discarded scraps of newspaper that I would find lying around my town, both to improve my reading and to learn about what was happening in the world. At home, we got our news through a small battery-powered radio most evenings as we sat on the floor eating our dinner. After finishing primary school, I attended a Catholic high school. In 2012, when I was 16 years old, based

on the results of the Malawi School Certificate of Education (MSCE) exams — an annual standardized national test that usually over 100,000 high school students take in their final year to graduate — I was one of six girls, out of the entire country, who won scholarships to study abroad.

I was lucky. Three of the six were awarded scholarships to study in China. I and two others got scholarships to study in the United States. Ironically, we were the runners-up.

So, the following year, at age 17, I boarded an airplane in Lilongwe, Malawi, and after several flights arrived at Troy University in Alabama. I had never been on an airplane and had not been outside of Malawi. It would be nine years before I would see my family again.

Malawi is what could be called a quasi-socialist country, with the government providing most services. When I left home, my plan was to study economics in America so that I could return to Malawi and help the government deliver services more efficiently. But I was astonished by what I found in the United States. While only less than a quarter of Malawians had easy access to water and electricity, in the U.S., nearly everyone did. That was only the beginning of the unimaginable prosperity I saw all around me. I wondered, how do they do it? What is it about America that created this remarkable standard of living and the freedom and opportunity that go with it?

In my economics classes, I studied thinkers like Friedrich Hayek and Ludwig von Mises. I began to understand how the free enterprise system generates America’s wealth. I stayed on at Troy to obtain my master’s degree in economics. And by the time I earned that degree, my career goals had changed. I wanted to work for a policy organization that advocates for free markets and limited government.

That is what brought me to Center of the American Experiment in Minnesota, a long way from where I started out in Malawi.

An immigrant’s perspective

When Gallup surveyed American adults in 2001 on how proud they were to be American, 55 percent said they were extremely proud, and altogether, nearly 9 in 10 adults said they were extremely or very proud to be American. That was 22 years ago, and things have changed.

In their June 2023 survey, Gallup reported that only 39 percent of adults were extremely proud, and 67 percent were extremely or very proud to be American. That decline in patriotism is especially stark for young adults. While 10 years ago, 85 percent of young adults aged 18 to 29 were extremely or very proud to be American, this year for those aged 18 to 34, the figure was down to 59 percent. This year, half of all adults over 55 are extremely proud to be American, but only 18 percent of adults aged 18 to 34 feel the same way.

Surveys from YouGov, Morning Consult, and Pew Research Center, among others, have found a similar trend of growing skepticism about the United States among young adults. In addition to their waning patriotism, young American adults are becoming even less likely to support free enterprise — the U.S.’s long-defining economic system.

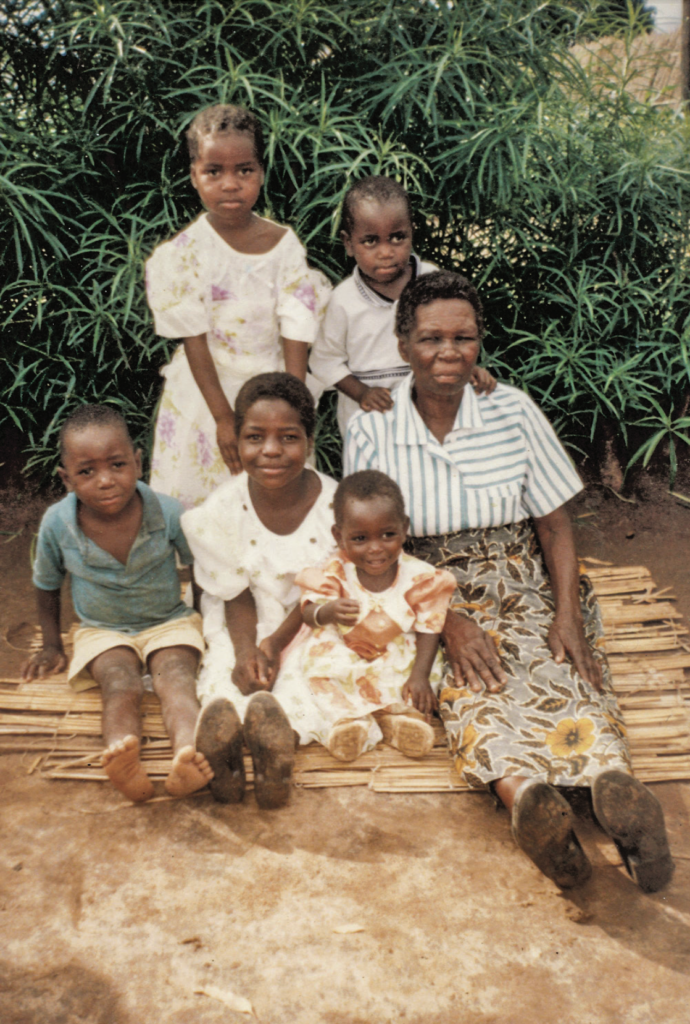

from left) with her family in Malawi on Christmas Day in 2004.

As an immigrant born and raised in a developing country, I find it hard to sympathize with my generation’s misgivings about capitalism generally and the United States specifically, a country that has tremendously improved my life. No country is flawless. But given the chance, I would wholeheartedly choose to be in America.

To come to the United States, a country where electricity and running water are unremarkable occurrences, not luxuries as they are in Malawi, has opened me up to a world of endless possibilities. Even as a college student with nothing to my name, my life became exponentially better than I could have imagined in my formative years of living in Malawi. Here, I have come to enjoy some of the highest standards of living in the world. There is such a level of abundance and convenience in this country, that I sometimes tend to forget where I came from.

In my 10 years of living in America, I have not worried about issues like electricity blackouts or wondered where I would get drinking water, let alone if I would have enough to eat. Yet years ago, something as seemingly trivial as accessing water took up hours of my day. Now, like most Americans, I reserve my frustration instead for slow internet, delayed Amazon packages, bad drivers, and bad hair days — a testament to the massive progress that this country has made in moving beyond subsistence.

Malawi and the United States

Between 1891 and 1964, Malawi was a British protectorate originally named the British Central Africa Protectorate. The British changed the name to Nyasaland in 1907 after the country’s biggest lake, Nyasa, which is a tribal word for lake. (In English, Lake Nyasa essentially translates to Lake Lake.) After independence in 1964, it ceased to be called Nyasaland and became Malawi — meaning flames.

Regardless of the exact origins, with independence the new name symbolized a return of the country from the British settlers and the beginning of a new dawn. Independence carried with it the idea of freedom, self-governance, and, more importantly, economic development. History, however, proved otherwise.

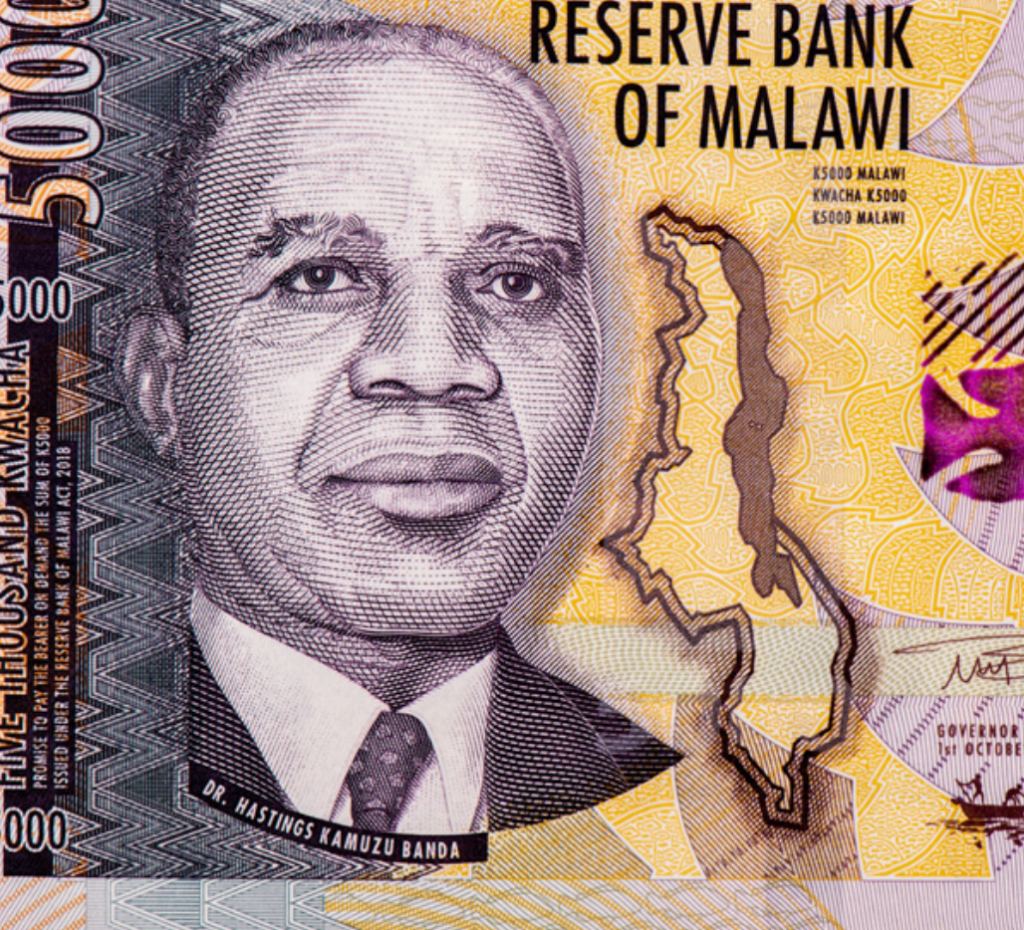

The next 30 years after independence were followed by brutal dictatorship, which necessitated a second fight for independence, this time from an autocratic domestic government. Initially serving as prime minister starting in 1963, Dr. Hastings Kamuzu Banda later ruled as president starting in 1966 when Malawi became a republic. In the same year, through an Act of Parliament, Malawi also became a one-party state. Banda was proclaimed president for life in 1971 by the legislature.

During his reign, which ended in 1994, there was never a presidential election. Every Malawian had to pay homage to Banda. He was to be thanked for all good things, even the sun’s rising. Dare disrespect the president, and you might find yourself thrown into a crocodile-infested dam. During Banda’s 30-year rule, thousands of his opponents were jailed without trial, killed, tortured, or forced into exile if they dared to speak out against the atrocities perpetrated by his government.

As for economic development, according to data from Penn World Table, Malawi’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita grew rapidly after independence, peaking in 1985 at $1,544 (in constant 2017 dollars). After that, it started declining and reached $1,215 in 1994.

Unfortunately, democracy did not equate to major changes in the country economically. As of 2019, Malawi’s GDP per capita was approximately $1,161. In the period through which I lived in the country — between 1996 and 2013 — GDP per capita ranged from a low of $856 (in 2002) to a high of $1,623 in 2008. After 2008, GDP per capita declined to $1,206 in 2013.

Data from the World Bank includes more recent years and is also the most frequently used for international comparisons. According to that organization, after controlling for purchasing power differences, when I lived in Malawi, GDP per capita ranged from a low of $1,077 in 1996 to a high of $1,368 in 2013 (in constant 2017 dollars). In the United States, however, GDP per capita in the same period ranged from $44,000 to about $56,000. For 2022, GDP per capita in the U.S. was $64,407 — about 43 times higher than Malawi’s.

Certainly, money is not the sole measure of prosperity. But things like education, infrastructure, and health care require massive investments, which poor countries like Malawi lack. The result is that by almost every indicator of well-being, Malawi trails the United States by a huge margin. Compared to U.S. residents, Malawians are more likely to live in extreme poverty, more likely to be food insecure, and less likely to have access to clean electricity and cooking fuels, which in turn makes them more likely to die from indoor pollution. Malawians are also less likely to have access to health care and more likely to die young, are more likely to receive a poor-quality education and less likely to finish secondary education. They are also less likely to have access to safe water and basic sanitation services and, therefore, are more likely to die from causes attributed to unsafe water or sanitation. As recently as 2021, Malawians are less likely to own mobile phones and have access to the internet.

The idea of America is worthy of pride

Every year, thousands of people risk their lives to come to this country because there is a level of opportunity and freedom offered here that is rarely found elsewhere. Unlike most immigrants, I wasn’t actively looking to come to the United States, but that’s only because I had no realistic means of getting myself to this country. Certainly, coming from one of the poorest countries in the world gives me a bleak point of reference. But that is also what makes it particularly easy for me to appreciate this country, the institutions on which it was founded, and its unique standing even among the world’s most developed countries.

It should be cause for concern that some groups, such as the non-college-educated, feel denied the opportunities and benefits that come with living in such a prosperous country. However, I object to those who claim that the solution to this situation is turning America into a socialist “paradise” — as many young people nowadays seem to prefer. Even with its problems, America remains one of the best countries in the world in which to be born and to live, mainly thanks to this country’s (somewhat diminishing) commitment to upholding the founding principles of liberty, limited government, and free enterprise. These principles are what have elevated this country above all others.

Everyone fortunate enough to be an American should not only be proud of this country but actively defend those principles. The United States is a symbol of what human ingenuity can achieve in the absence of government interference. It is a nation conceived in liberty, and it is only by upholding that liberty that we can fulfill our potential as a place where everyone is guaranteed the opportunity to pursue happiness as they see fit. Coming to the United States has changed my life for the better, and for that, I count myself lucky and feel extremely proud to live here. Considering the alternatives, everyone should.

Subscribe to Thinking Minnesota

Are you getting our free quarterly magazine? If not, sign up today to get original news stories, exclusive interviews, historical analyses and more delivered right to your doorstep.