An ethical failure

Minnesota is NOT keeping the Pension Promise

I have an old friend who worked as an administrative assistant in the public sector. After many years on the job, she wanted to do something really different. But when she checked her pension formula, she discovered that she would get a much smaller pension if she did not stay in the public sector for a full 25 years. That is because public pensions “back load” the benefit, favoring career employees.

My friend continued to work dutifully, but she missed out on a chance to try something new. While always grateful for her job, she did not really want to be there anymore. As she counted down to retirement, her department missed out on getting a new person with a different skill set and enthusiasm for the job. Does that make any sense in a mobile economy where people change jobs and careers five to seven times over a lifetime?

Inadditiontobeingrigidandoutof date, Minnesota’s pension plans are falling farther behind in funding the promises they have made to employees. Yet, as I demonstrate in the newly released Minnesota Policy Blueprint chapter, Keeping the Promise: Securing Retirement Benefits for Current and Future Public Employees, the cost of these plans is going up for both taxpayers and employees. Here are some Quick Facts to ponder:

Pension Quick Facts from Keeping the Promise and the Minnesota Policy Blueprint

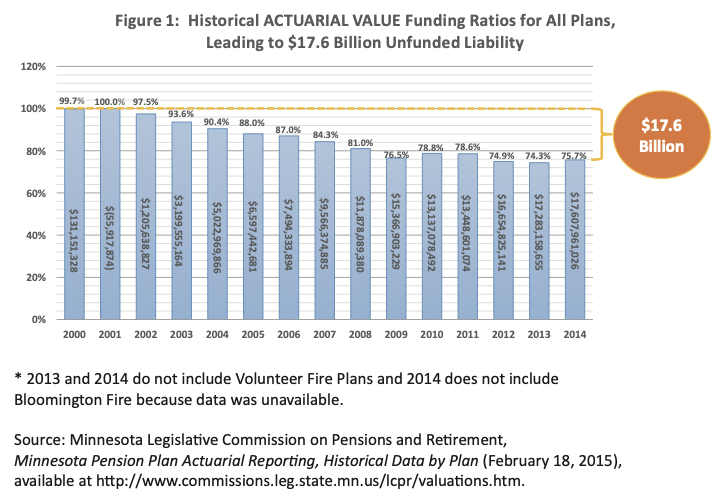

- Unfunded liability in 2013 is $17.3 billion; in 2014 it went up to $17.6 billion (see Figure 1)

- The unfunded liability may actually be over $43 billion

- Minnesota has 76 cents on the dollar to pay pensions (see Figure 1)

- Total required contributions to make pensions whole for 2014 were $2.6 billion but Minnesota only paid $2.2 billion, with a deficiency of $377 million

- Minnesota has missed the full annual contribution since 2003 by hundreds of millions each year

- The unfunded liability ($1.27 billion) was almost equal to the cost of benefits earned that year plus expenses ($1.29 billion)

- A large chunk of the contributions in 2014 was allocated to the amortized unfunded liability ($897 billion) but the unfunded liability just keeps growing

- Employees paid $386 million and employers paid $511 million of the unfunded liability of $897 million

- Minnesotans kicked in an additional $110 million in direct state aid and employer contributions in 2014 to prop up some funds

Did you know there are almost 312,000 public employees in Minnesota contributing to a public pension fund and over 202,000 retirees, survivors and disabled people relying on a pension check? That is over 11 percent of the state’s population, so we better figure this out, and soon.

We timed the updated edition to coincide with the fall interim meetings of the Legislative Commission on Pensions and Retirement.

This 14-member commission, made up of members from the House and Senate, is chaired by Rep. Tim O’Driscoll (GOP-St. Cloud). The Vice Chair is Sen. Sandy Pappas (DFL-St Paul). The commission meets regularly during the legislative session to pass an annual “omnibus

bill” but typically takes up policy issues during the interim when members and staff have more time to devote to this complex topic.

The interim meetings come at a time of great volatility in the world of public pensions. Following the Detroit and other municipal bankruptcies, there were big announcements from funds around the country as managers struggle to close the gap between the promises made to retirees and the assets available to pay them.

For example, the California behemoth CalPERs, which sets the trends for public pensions, announced a plan to lower investment return expectations from the current 7.5 percent to 6.5 percent.

The New York State Common Retirement Fund has gone from an 8.0 percent assumed rate of return five years ago to 7.5 percent, and it announced that it is lowering it again to 7.0 percent. New York’s Comptroller said, “From a long-term perspective, we think it’s a prudent move in that it better positions the fund to have more realistic expectations about what our investment returns will be.”

These are huge changes in big “Blue” states that will have to be paid for by taxpayers and employees alike—how that mix works out is up to each pension fund. This comes on the heels of big increases that have already crowded out other spending at the state and local level. The U.S. Census Bureau reports that local and state contributions to retirement systems have already more than doubled over the last decade, while employee contributions rose about 50 percent.

Maybe that is why, in spite of big increases in educational spending, Minnesota keeps seeing school referenda for higher levies. Or local government increases in property taxes.

So where is Minnesota on this key assumption?

With the exception of the Teachers Retirement Association (TRA), which is in the worst shape of all the major funds, the pension funds lowered return expectations from 8.5 percent to 8.0 percent. So while Minnesota is headed in the right direction, it is still well above the national average, and the national average is still too high.

What does that mean? It means the pension plans are overestimating how much the state will earn on investments and thus underestimating how much to put aside to fund the pension promised. Hence, the growing unfunded liability.

When we polled Minnesotans last year as part of the Blueprint project, a majority (51 percent) of Minnesotans said that the financial solvency of the state’s system of public pensions poses a potential problem. Nearly two-thirds (64 percent) think that public employees should transition to a kind of 401(k)-style pension system that is commonly used by private sector employers. That means the Center has done a good job of educating the public.

And therein lies the solution. While big unions, and the politicians they elect, will fight to keep a complicated pension system that gives them control over employees like my friend, the voting public knows it is time to give employees the freedom to choose a savings plan that puts them in charge of their own assets and retirement plans. 401(k) plans are far from perfect but they are fully funded every pay period. That would be a good place to start keeping the promise.