Aspirations of mediocrity

A revealing book about government schools details the desperate need for change.

Forty years ago, the United States National Commission on Excellence in Education warned in its report “A Nation at Risk” that the “educational foundations of our society are presently being eroded by a rising tide of mediocrity that threatens our very future as a nation and a people.” [Emphasis added.]

Sadly, despite the years that have passed since, this warning about the sorry state of government schools rings just as true today, if not more so, as it did in 1983.

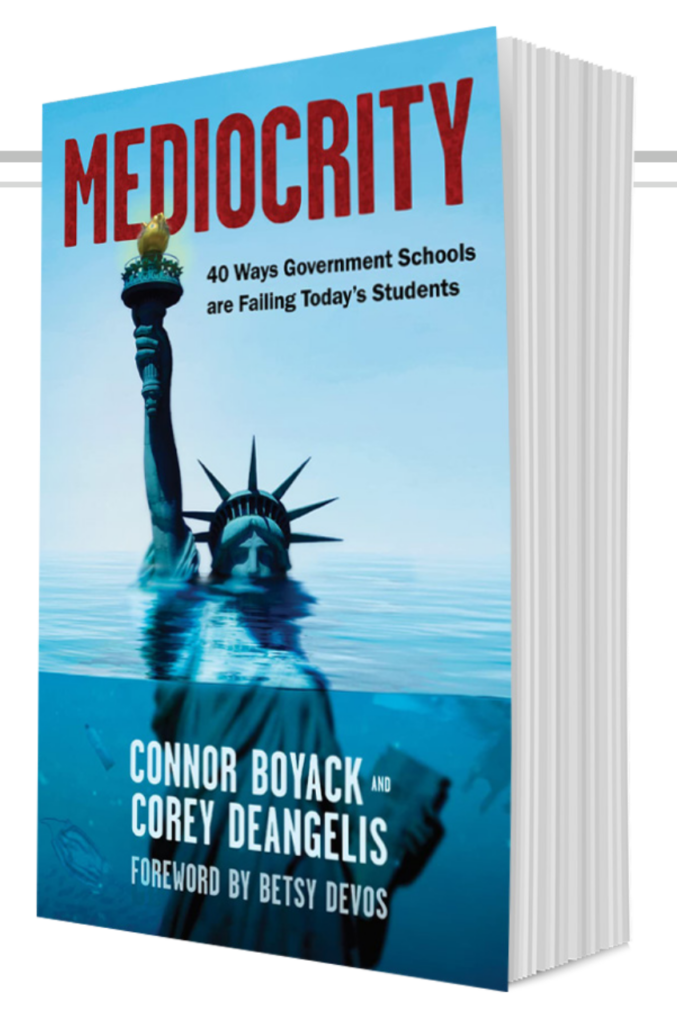

In their latest book, Connor Boyack and Corey DeAngelis detail how the tide of mediocrity is now a tsunami of low expectations and poor performance, suggesting the desperate need for alternative solutions.

Mediocrity: 40 Ways Government Schools are Failing Today’s Students — with the number 40 chosen in reference to 40 years since “A Nation at Risk” — is not a book of solutions, but rather a book that focuses on the problems plaguing America’s government schools and, like any good warning sign, encourages its readers to change their behavior. A call to arms of sorts for parents, grandparents, and those concerned about the current state of the education landscape in America.

The Latin root word of education — educere — means to draw out, to lead out. (I previously taught 6th grade Latin.) But as Boyack and DeAngelis expertly document, this process of awakening and helping students discover themselves as they discover the world around them is being smothered.

From declining test scores and using students as political pawns to dumbed down curriculum and students not being “college ready,” the shortcomings of America’s government schools are intentional and methodical, as Boyack and DeAngelis describe. Add on the attempts to erase parents’ role in their children’s education, or chastise them for trying to be involved — even concerning medically life-altering decisions — and the deterioration of the system takes on a whole new meaning.

“The idea of government schools being ‘too big to fail’ might seem odd since there is evidence everywhere of the institution’s consistent failure,” Boyack and DeAngelis write. “But failure looks different when it is incremental, just like the proverbial frog in the pot of steadily boiling water — it is hard to see the destruction of a system when it looks like extremely slow decay.”

Consider who contributed to the schematics of today’s government schools and what they prioritized. Not only is this factory-model system no longer relevant for today’s economy, but the fundamental intent of such a system — to strengthen a child’s dependence upon the state — is at odds with the diverse views of the families it is supposed to serve, continue Boyack and DeAngelis.

Take Horace Mann and John Dewey, for example, two leading education reformers in America. Mann admired a schooling system being developed at the time in Prussia that represented an “authoritarian, top-down model that emphasized the collective over the individual.” Through his quest to industrialize education, the framework he set up — the foundations of a system — was picked up by others such as John Dewey, a secular humanist who theorized an atheist utopia. As this schooling system was being built across the country, Dewey and his like-minded reformers were able to, in Dewey’s own words, “build up forces…whose natural effect is to undermine the importance and uniqueness of family life.” As Boyack and DeAngelis summarize, “Academics were secondary; social transformation was the key, and families stood in the way.”

Does this mean that all the kind, hardworking teachers at the nearby elementary school share this goal to socially engineer the rising generation? Of course not. I come from a family of public school teachers — and was one myself — who aspire to help students achieve their fullest potential. The problem, Boyack and DeAngelis point out, is that good teachers “can only do so much in a system that constrains their growth.”

Therefore, it is time to empower students, families, and teachers to pursue excellent alternative systems. The current monopoly of the government school system needs competition to rise above the mediocrity of past decades. “We have seen the lack of competition lead to complacency — schools not evolving to teach students the skills needed for success in the current economy,” note Boyack and DeAngelis. But teachers’ unions and others in the system oppose empowering families through education freedom because of the competition it introduces. “Naturally, no monopoly wants competition; the privileged position of the status quo is defended until the institution is forced to reform by external pressure. If we want to fix the current mediocrity, we have to dismantle the monopoly.”

Perhaps most concerning is that there actually is general recognition that our country’s schools are in a sad state, but the pervasiveness of the problems is often not known — or accepted. Parents may shelter themselves from confronting such realities because their local neighborhood school couldn’t be part of the problem, right? It is difficult to accept new information that challenges our beliefs, Boyack and DeAngelis continue. So, there will be those who minimize or dismiss the 40 examples shared in this book and write them off as being too critical.

But there is another option for readers: heeding the warnings and taking action — “muster up the courage and commitment to pursue superior alternatives that will be a better fit for each of your children while minimizing or eliminating the negative aspects of their school experience,” Boyack and DeAngelis conclude.

“Our future as a country depends on fixing this foundational problem, and conventional approaches to improvement won’t work. We will not overcome mediocrity through more teacher training, more taxpayer dollars, or more testing and technology.” The best course of action is to “stop telling kids to tread water and, instead, throw them a lifesaver.”