Border battle

Minnesota’s economy no victory for Dayton

There’s a border battle going on between Minnesota and Wisconsin, a battle between the policies advanced by Gov. Mark Dayton and Gov. Scott Walker. The two states have long shared similarly sized populations and economies, as well as similar politics. But since being elected in 2010, each governor pushed and passed dramatically different policies. Dayton raised taxes by over $2 billion, increased spending by over 10 percent per person and hiked the minimum wage. At the same time Walker cut taxes and ended collective bargaining requirements for public employees. As the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel put it, “Wisconsin is getting its most conservative governance in decades. Minnesota is getting its most liberal governance in decades.”

After taking these divergent paths, people naturally started comparing which path would lead to better economic outcomes. Despite the fact that Dayton’s tax the rich, spendthrift policies have barely been in place for two years, liberals are already claiming victory.

Former Minneapolis Mayor R.T. Rybak, presently a vice chairman of the Democratic National Committee, penned a Star Tribune column in April claiming Walker “destroyed [Wisconsin]’s economy,” which was followed by President Obama’s July trip to La Crosse, Wisconsin where he declared, “Minnesota’s winning this border battle.” Liberals simply can’t get enough of comparing Dayton and Walker.

Liberal Claims Fail to Square with Economic Realities

Liberal victory speeches touting Minnesota as the shining beacon of progressive policy success simply does not square with two simple economic realities revealed in the following graphs.

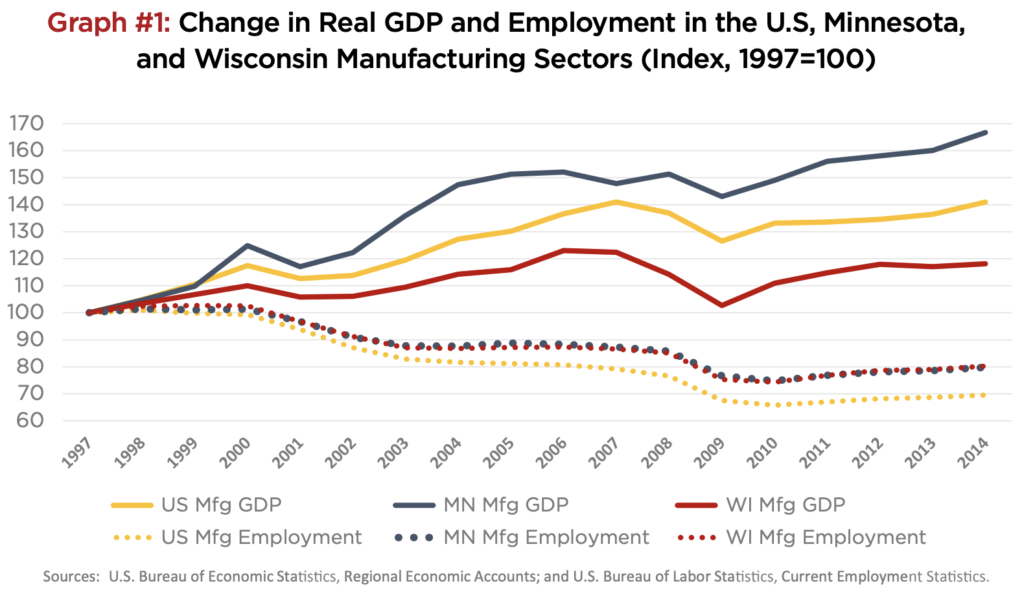

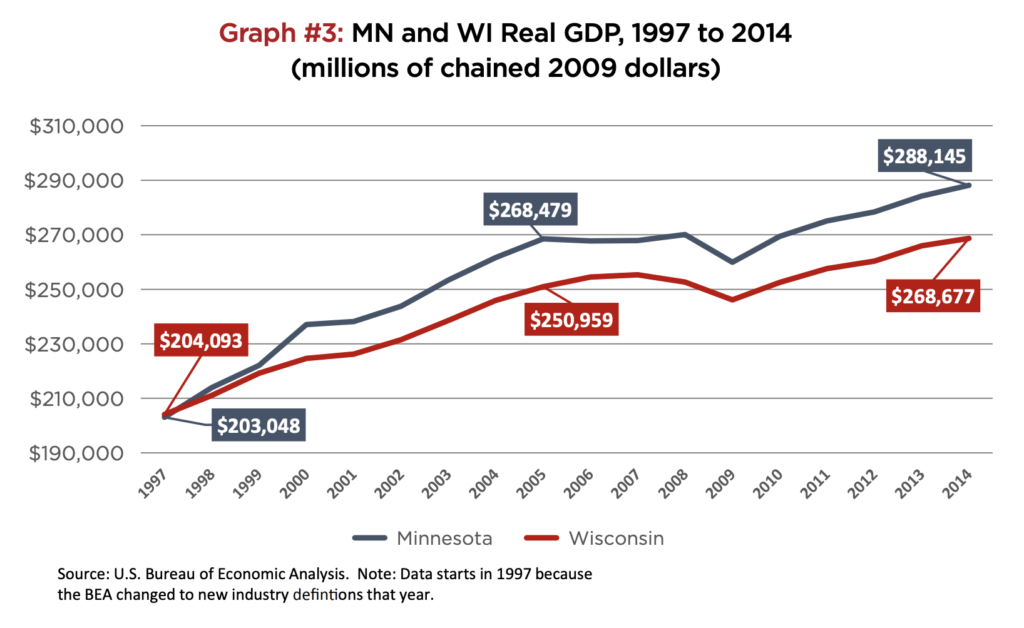

First, Minnesota’s economy pulled ahead of Wisconsin’s well before Dayton and Walker took office. Graph #1 shows Minnesota’s economy was just a hair smaller than Wisconsin’s in 1997, but began growing larger in 2000. By 2005, Minnesota’s economy grew to be 6.53 percent larger and since that time, not much has changed in relative terms. These data show whatever lifted the Minnesota economy above Wisconsin must be linked to something that not only predates Dayton and Walker, but even predates Governors Tim Pawlenty and Jim Doyle.

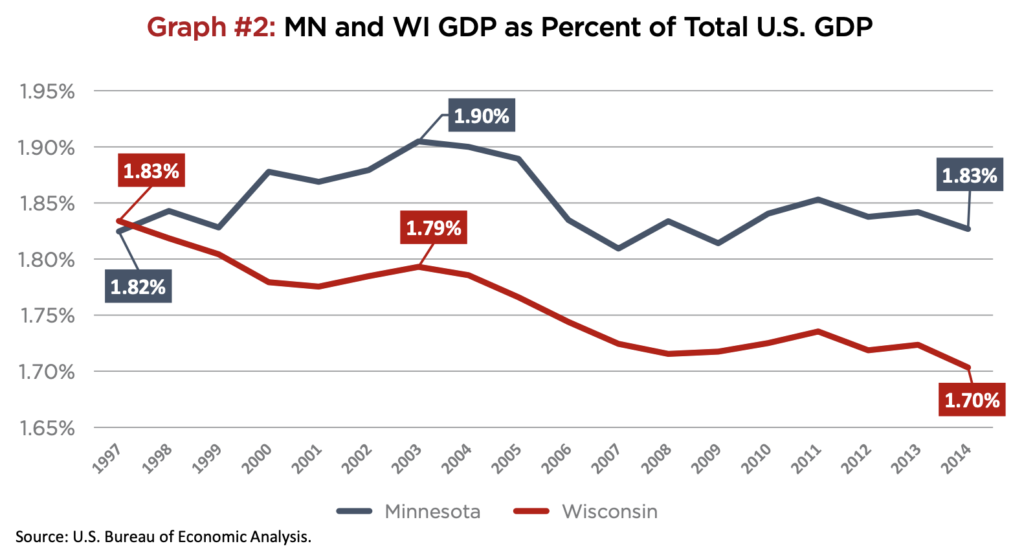

Second, though Minnesota’s economy might beat Wisconsin’s, both states have lost ground to the rest of the country. Graph #2 shows Minnesota and Wisconsin GDP as a percent of U.S. GDP. The slice of the U.S. economic pie declined for both states between 2003 and 2007 and has remained relatively steady since. This strongly suggests neither state has the ideal mix of policies in place to compete for a larger portion of the U.S. economy. Minnesota is therefore no example to the nation of a progressive policy triumph.

Manufacturing Led Minnesota’s Growth

Contrary to the liberal storyline that Minnesota’s high taxes don’t hamper growth, a closer look at economic data strongly suggests lower taxes are part of what pushed the Minnesota economy ahead of Wisconsin and, more importantly, can be part of strengthening Minnesota’s economy in the future. Making the connection between taxes and growth starts by digging deeper into what drove Minnesota’s growth over Wisconsin’s.

Compare economic growth in Minnesota versus Wisconsin across the major industry sectors and a surprising fact stands out. Minnesota manufacturing is actually the leading industry sector responsible for lifting Minnesota’s economy over and above Wisconsin’s.

Between 1999 and 2005—the period when Minnesota GDP grew from roughly the same size as Wisconsin GDP to 6.5 percent larger—Minnesota added $14.6 billion (real 2009 dollars) more to its economy than Wisconsin. Growth in Minnesota’s manufacturing industry led the way and beat Wisconsin growth by $6.2 billion, the largest amount for any major industry sector. The next closest industry was “finance, insurance, real estate, rental, and leasing,” which beat Wisconsin growth by $3.7 billion.

Extending the period to 1997 to 2014 (the full period of available, comparable data), Minnesota manufacturing sector growth exceeded Wisconsin’s by $8.5 billion. In percentage terms over this period, the Minnesota manufacturing sector grew by 66.7 percent, compared to 18.1 percent for Wisconsin and 41.0 percent for the nation. All of this goes to show Minnesota’s manufacturing sector has consistently outperformed the U.S. and Wisconsin in recent years.

So why is Minnesota’s manufacturing sector experiencing stronger growth than Wisconsin and the U.S.?

The Rust Belt Effect

One answer might be that Minnesota was never part of the so-called “Rust Belt,” the regional belt of more labor-intensive manufacturing extending from Utica, New York to Milwaukee, Wisconsin that has struggled against automation and cheap global labor. On this theory, Minnesota’s economy has not been weighed down by the contraction of Rust Belt manufacturers nearly as much as Wisconsin and the U.S. With fewer manufacturers contracting, Minnesota should be experiencing stronger rates of economic growth and lower rates of job losses in the manufacturing sector.

The chart below suggests there may be some truth to this theory when comparing Minnesota to the U.S. Relative to the U.S., Minnesota manufacturing output is clearly experiencing higher growth—66.7 percent in Minnesota versus 41.0 percent in the U.S.—along with lower job loss rates—20.2 percent in Minnesota versus 30.4 percent in the U.S.

But when comparing manufacturing employment in Minnesota to Wisconsin, the states are nearly identical. In fact, manufacturing employment declined a touch less in Wisconsin (19.8 percent) than in Minnesota. If employment contractions are a good indicator of being hit by Rust Belt problems, Minnesota and Wisconsin are being hit the same. So, the Rust Belt experience does not provide a satisfying answer for what separates Minnesota and Wisconsin manufacturers. Something else must be going on.

Minnesota Manufacturers Pay Far Lower Taxes

Differences in corporate tax structure offer a much more complete and satisfying answer to why Minnesota manufacturer growth outpaces Wisconsin’s. As it turns out, many Minnesota manufacturers pay relatively low taxes, while Wisconsin manufacturers pay very high taxes.

Though Minnesota and Wisconsin are both higher tax states, the specific state tax burden for a taxpayer—the amount people and businesses actually pay—can vary quite substantially across income levels and business sectors. Simple comparisons of per capita tax burdens or corporate tax rates fail to account for what a business actually pays.

Indeed, different types of businesses can pay very different tax amounts depending on the type and value of their property, the proportion of sales sold in-state, unemployment insurance tax rates, sales tax rates and whether they apply to business inputs, and various tax incentives offered to new and expanding businesses.

To help understand what actual businesses pay in taxes from state to state, the Tax Foundation in collaboration with accounting firm KPMG developed an apples-to-apples comparison of business tax costs by state. Tax Foundation economists developed seven model firms and KPMG then established what these firms would pay in taxes depending on whether they were mature firms or new firms. Of the seven firms, one was a capital-intensive manufacturer and another was a labor-intensive manufacturer.

The results: Minnesota tax burdens ranked very high for four of the seven mature firms. The four high tax firms included corporate headquarters (48th), retail store (49th), call center (45th), and distribution center (42nd).

But despite its high tax reputation, Minnesota ended up being the 13th lowest tax state for a research and development facility and the 17th lowest tax state for labor-intensive manufacturing. But here’s where Minnesota really stood out: The state imposed the 2nd lowest tax burden on capital-intensive manufacturers. Yes, despite Minnesota imposing the third highest corporate income tax rate in the country, the actual taxes paid by capitalintensive manufacturers are the 2nd lowest in the country.

Across the border, Wisconsin’s tax burden on capital-intensive manufacturers ranks among the worst at 46th and, at 42nd, its rank for labor-intensive manufacturers isn’t much better.

Single Sales Apportionment and No Throwback Rule

The reason Minnesota manufacturers pay such low taxes is largely because Minnesota applies a single sales apportionment factor formula and no “throwback rule” to corporate taxes. Minnesota’s corporate income tax is based entirely on the apportionment of sales within the state and does not factor in property or payroll like many other states do. Thus, a manufacturer with 10 percent of sales to Minnesota customers will only pay taxes on 10 percent of income. This is a huge tax advantage to businesses that sell a large proportion of their products out of state, such as General Mills, 3M and Medtronic.

However, the main tax advantage for Minnesota manufacturers is the absence of a “throwback rule.” Many states, including Wisconsin, treat sales shipped to other states as in-state sales for the apportionment formula when the corporation is not subject to taxation by the other state. In effect, the sale is “thrown back” and treated as if it was sold in the originating state, which dramatically increases the portion of corporate income subject to taxation for any company that ships a lot of product beyond the state’s border.

So, for tax purposes in Minnesota, Cheerios, Post-it Notes and pacemakers sold to customers in Vegas, stay in Vegas. Windex shipped from Mt. Pleasant, Wisconsin does not receive the same favorable tax treatment.

How unfavorable are Wisconsin’s taxes on manufacturers by comparison? Based on the model firm presented in the Tax Foundation report, the actual tax burden for a mature capitalintensive manufacturer is 4.0 percent in Minnesota versus 16.5 percent in Wisconsin. New manufacturers can expect a 4.6 percent rate in Minnesota versus a 9.8 percent rate in Wisconsin.

Though taxes are only one part of a firm’s decision to open or expand, these tax rates strongly favor opening or expanding a manufacturing business in Minnesota versus Wisconsin. No business can ignore a 12.5 percentage point difference or even a 5.2 percentage point difference in tax rates.

The Value of Special Incentives

To put a face on all these numbers, a couple years ago Shutterfly was in the news because it chose to locate a new manufacturing facility for its products in Shakopee, Minnesota, bringing up to 1,000 full- and part-time jobs to the state. Shutterfly wanted a Midwest facility close to Midwest customers and the choice largely came down to Minnesota versus Wisconsin. According to Gov. Mark Dayton, “The plant would be developing in Wisconsin rather than Minnesota if it were not for incentive financing.” And nearly every news outlet dutifully reported on how a $1 million grant from the state and $1.5 million in tax breaks from Scott County lured Shutterfly to Minnesota.

News outlets, however, completely neglected the most important tax difference between Minnesota and Wisconsin—Minnesota’s lack of a throwback rule. One must wonder if

Shutterfly executives were laughing all the way to bank. Would the company really have opened a plant in Appleton, Wisconsin when the sale of photo books, cards, calendars and photo gifts to customers in other Midwestern states would be thrown back to Wisconsin and taxed? Very, very doubtful. Shutterfly opened and will thrive in Minnesota in no small part to Minnesota’s low tax burden on this particular industry. No doubt other manufacturers are doing the math and choosing Minnesota over Wisconsin and other states as well.

But manufacturing is just one sector of Minnesota’s economy. Other industries face among the highest tax burdens in the country. Take away manufacturing and the rest of Minnesota’s economy consistently underperforms the U.S.

Minnesota’s economy can do better.

In the end, a closer look at Minnesota’s border battle with Wisconsin actually shows how taxes matter and how low taxes promote growth. Low taxes on Minnesota’s manufacturing sector help spur strong growth and it’s long past time the state give other industries the same low-tax advantage to grow.