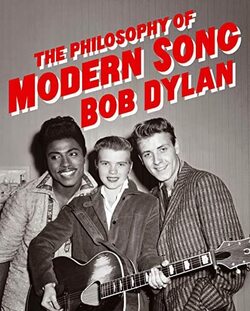

Bringing it all back home

Bob Dylan’s newest book speaks to the present through the songs of the past.

Bob Dylan’s 2004 memoir, Chronicles: Volume One, told you little about Dylan but much about his music. His new book, The Philosophy of Modern Song, does the opposite.

You won’t learn much about modern song here. Of the 66 songs Dylan discusses, 42 percent are from the 1950s — 14 percent from the modal year of 1956 alone — while there are just four songs from the last 32 years. Hip hop, one of the dominant forms of American popular music in the last four decades, is completely absent. Dylan mentions rappers Biggie Smalls and Jay-Z only to say that Elvis Costello preceded them (and that he preceded Costello), and he dismissively contrasts the “gangstas” of rap with “real gangsters like Jesse James,” which is unfair to Smalls who was, after all, shot dead.

The book is, in fact, anti-modern. It is both a love letter to and a requiem for the America the now 81-year-old Dylan grew up in, when he was Robert Zimmerman in Hibbing, Minnesota. “You’re getting flashbacks from the past,” Dylan writes of Roy Orbison’s “Blue Bayou,” “and you want to go back to all that, before you get carried away too far and are ravaged by time.”

Like another American cultural icon, Clint Eastwood in 2009’s Gran Torino, Dylan invokes Detroit at its peak as an image of America at its peak. Discussing Bobby Bare’s 1963 track “Detroit City,” he writes, “When this song was written, Detroit was a place to run to; new jobs, new hopes, new opportunities. Cars came off the assembly lines and straight into our hearts. Since then, like many American cities, it has ridden a roller coaster between affluence and decline.”

This theme of decline recurs throughout the book. Of Jackson Browne’s 1976 record “The Pretender,” Dylan writes: “The Platters sang of the Great Pretender back in 1955, but like many things even pretenders got devalued between the fifties and the seventies.”

Dylan offers movies as a case study in this devaluation. Relating The Drifters’ song to the teenage rite of passage “Saturday night at the movies,” he writes, “had always been more than just a chance to share a bucket of popcorn with a date in the last row of the balcony. The best features contained wisdom, aphorisms that hinted at a moral code…” And “High Noon,” Dylan explains, “is far from a mere western. It’s a nuanced tale of a man facing down the clock, learning about bravery, loyalty, faith, and love.” But “In the seventies,” he argues, “antiheroes like Butch and Sundance, Dirty Harry, Super Fly, and Travis Bickle thumbed their noses at fifty years of ramrod-straight backbones and firm jaws.” “[T] he antihero crowded real heroes off the screen until anyone who even hinted at Gene Autry’s cowboy code was banished and branded obsolete.” “People keep talking about making America great again,” he concludes, “Maybe they should start with the movies.”

“Every generation gets to pick and choose what they want from the generations that came before with the same arrogance and ego-driven self-importance that the previous generations had when they picked the bones of the ones before them,” Dylan writes on The Who’s 1965 record “My Generation,” and he seems to think that that generation discarded much they should have retained. Does he try to distance himself from this? He notes that “Pete Townshend was born in 1945, which puts him at the front end of the baby boomer generation” but it also puts Dylan — born in 1941 — into the preceding one, that of Marlon Brando and “the first wave of rockers,” which “fell somewhere between the greatest generation ever and the baby boomers; too young to fight against the Nazis, too old to go to Woodstock,” which “set the stage for the sixties.” [Emphasis added]

Dylan was invited to play Woodstock but declined. He was up the road at his farm with his family having just released a country and western album. He “set the stage,” then abdicated his role as Voice of a Generation in 1966. But, however unwillingly, he had been that voice, singing in 1964:

Come mothers and fathers

Throughout the land

And don’t criticize

What you can’t understand

Your sons and your daughters

Are beyond your command

Your old road is rapidly agin’

Please get out of the new one if you

can’t lend your hand

For the times they are a-changin’

More recently, he has been singing the songs of those “mothers and fathers.” In 2015, he recorded a Frank Sinatra cover album. For 2016’s Fallen Angels and his 2017 triple album Triplicate he revisited the Great American Songbook, covering standards like “As Time Goes By” and “The Best Is Yet to Come.” There have been many Bob Dylans over the decades: protest singer, electric poet, born again Christian. Maybe we shouldn’t be surprised by his latest incarnation: cultural conservative.