COVID confusion

An objective look back reveals how the Walz administration bumbled through its reaction to the pandemic.

The United States recorded its first case of COVID-19 in Washington state on Jan. 19, 2020. The virus was first detected in Minnesota on March 6. Gov. Tim Walz said then at a press conference: “State and local governments have been working hard for about the last month to prepare, as many in the private sector have. I’m confident Minnesota is prepared for this.”

The data accumulated over the year that followed, however, show that Walz’s confidence was misplaced and his state was mismanaged.

The first ‘lockdown’

Let’s go back to the brink of last spring. Cases continued to mount. On March 13, Walz declared a state of emergency. On March 15, he announced a one-week closure of all Minnesota’s K-12 public schools. On March 16, he closed all non-essential businesses until March 27. And on March 21, the state announced its first COVID-19 death.

By March 25, the Department of Health had recorded 503 cases. Walz directed all Minnesota residents to stay home beginning at 11:59 p.m. on March 27 through 5 p.m. on April 10. The order permitted essential activities and services to continue; for example, with proper social distancing, people were allowed to exercise outdoors and visit grocery stores.

“We’re not going to stop this from spreading…but we can stop how fast it spreads and we can make sure that we protect those most vulnerable,” Walz said. Health officials predicted that about 15 percent of infections would require hospitalization and five percent would need intensive care. If the virus spread too rapidly, Minnesota’s 235 ICU beds would be overwhelmed, people requiring ICU treatment would not get it, and hey would die as a result. The point of staying home, Walz said, was to “flatten the curve,” pushing down the peak of infections by slowing the spread of the virus so that the health system would not be overwhelmed. “The thing that Minnesota is going to do is ensure if you need an ICU, it’s there,” he explained. “Buckle it up for a few more weeks.”

The model

These decisions were driven by forecasts made by a model built over a weekend by the University of Minnesota School of Public Health and state Department of Health. They warned that, without mitigation, COVID-19 could kill upwards of 74,000 Minnesotans and that the state’s ICU beds would be full within six weeks. Even with “vigorous public policy responses,” such as maintaining the stay-at-home order into May and social distancing into June, the model forecast that 22,000 Minnesotans would die from COVID-19 through March 2021.

On April 8th, Walz extended his stay-home mandate to May 4 based on Version 2 of the state’s model. This predicted a peak demand for ICU beds of 3,700 on July 13 and, again, 22,000 deaths. “We can say with 95 percent confidence that we are going to need a minimum of 3,000 beds starting in the middle of May. And that could be 3,000 beds starting in the middle of May. And that could be 3,000 beds as far out as the middle of July, depending on what we do social distancing-wise. and it could go higher,” Walz said. Version 3 of the model, which arrived in May, forecast that Minnesota would see 1,441 COVID-19 deaths by end of the month.

These forecasts were wildly off the mark. The actual death toll on May 31 was 1,039, off by 402, or 28 percent. Over such a small horizon, an error of this significance damns the model that produced it. Version 3 had also forecast a peak ICU demand of 3,397 beds on June 29. Only 85 were COVID-occupied on that date.

The model became such an embarrassing failure that it was quietly abandoned. On Oct. 29, KSTP’s Tom Hauser reported that a new model would show the efficacy of masking and varying degrees of shutdown. Nothing more has been heard of it.

The economy

The decisions driven by this model has disastrous economic impacts. In February 96,111 Minnesotans were unemployed. 3.1 percent of the labor force. Between March 16 and April 14, 409,574 Minnesotans applied for unemployment insurance. The state’s May unemployment rate hit 9.9 percent, its highest since at least 1976.

Some argued that this was a regrettable but necessary price to pay to slow the spread of COVID-19. But it was difficult to discern a pattern in the businesses deemed “essential” and “non-essential.” As Dave Orrick of the Pioneer Press asked Steve Grove, Minnesota’s Commissioner of Employment and Economic Development, on April 29: “I can go into Menards and buy a kite for my kid, but I can’t go into the Hub Hobby and do the same. If Hub Hobby were open, it would accomplish more for social distancing, no?” Indeed, the general rule seemed to be that the bigger the business, the better its chances of being deemed “essential.”

Care homes

As early as mid-March, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) issued guidelines to slow the spread of the virus for care home residents, which it deemed were at particular risk from COVID-19. “As we learn more about the coronavirus from experts on the ground, we’ve learned that seniors with multiple conditions are at highest risk for infection and complications,” CMS explained.

This was soon borne out in Minnesota. On May 6, it was reported that nearly 84 percent (407) of the state’s 485 COVID-19 deaths had been among people living in long-term care facilities, one of the highest percentages in the U.S. The following day, Walz announced a Five-Point Plan to protect care home residents. “Ensuring we are in a strong position to care for our most vulnerable populations is a top priority,” he said. “That’s why we are implementing a detailed new plan to make sure our long-term care facilities have the support and resources in place to protect residents and workers during this pandemic.”

The plan failed. About six months after its launch, care home residents accounted for 69 percent of Minnesota’s COVID-19 deaths. True, this was a fall from 84 percent, but the drop was due more to a rapid rise in non-care home deaths than any fall in care home deaths. Indeed, in the 46 days between March 21 and May 6, the average daily death rate was 8.7 in care homes and 10.3 outside. In the 158 days that followed, the daily death rate outside care homes had surged to 14.6, but the average daily death rate inside care homes had risen too, to 10.1.

The second surge

These failings notwithstanding, on April 29 Walz announced “Mission Accomplished.” “I today can comfortably tell you that, when we hit our peak — and it’s still projected to be about a month away — if you need an ICU bed and you need a ventilator, you will get it in Minnesota.” This was at a time when the state’s model was forecasting a peak of 3,700 Minnesotans needing ICU treatment for COVID-19 on July 13. On May 18, with an average of 662 new cases diagnosed in the previous seven days, the stay-at-home order expired, replaced with a “stay safe Minnesota” order. Stay safe simply meant to work from home if you can.

On July 22, with an average of 648 new cases in the previous seven days, Walz mandated that face masks be worn in stores, public buildings and indoor spaces. “If we can get a 90 to 95 percent compliance, which we’ve seen the science shows, we can reduce the infection rates dramatically, which slows that spread and breaks that chain,” he said.

This did not happen. Instead, the number of new cases rose from an average of 591 in the seven days up to and including Sept. 13 to 6,918 in the seven days up to and including Nov. 13. The second surge had arrived. But once again, state leaders were not prepared.

WCCO reported on Nov. 30 that the state was approaching ICU capacity, this when 400 Minnesotans were said to be receiving ICU care for COVID-19. How could this be when, on April 29, with an expected peak ICU demand of 3,700, Walz has said: “If you need an ICU bed and you need a ventilator, you will get it in Minnesota”? The stay-at-home order had been directed toward building up ICU capacity, from 235 beds to more than 3,000. But the state was now overwhelmed with a demand for 400 beds. If the mask mandate had failed in its stated aim, so, too, had the stay-at-home order.

State government was quick to blame Minnesotans for the failure of its policies. On Jan. 5, Kris Ehresmann, the Minnesota Department of Health’s director of infectious disease epidemiology, prevention and control, told MPR: “What has surprised us the most, is the lack of cooperation from the public.” In fact, data showed that Minnesotans had been complying. Carnegie Mellon University’s COVIDcast Real-time COVID-19 Indicators showed that, as of Nov. 30, 94.74 percent of Minnesotans were reported to be wearing masks most or all of the time while in public. Indeed, this was one explanation given for the near disappearance of seasonal flu — that the measures taken to slow the spread of COVID-19 had wiped out the flu. But clearly, for this to be the case, Minnesotans would have to have been complying with these measures.

After so much sacrifice, Minnesotans did not deserve to be thrown under the bus by a state government trying to excuse its policy failures.

To cover for these failures, Walz announced new restrictions effective Nov. 20. However, for all his repeated invocations of “the science” and “the data,” neither supported these new measures. With fears of a post-Thanksgiving surge, the size of indoor and outdoor private gatherings was limited to just 10 people and from no more than three households. Referring specifically to these measures, Ashleigh Tuite, an infectious disease modeler at the University or Toronto, called them unscientific and “bizarre.” Cinemas were closed, despite the fact that, as Dr. Peter Chin-Hong, an infectious disease specialist at the University of California-San Francisco said, there are “no documented COVID cases linked to movie attendance to date globally.” Gyms were closed, despite being linked to just 0.3 percent of Minnesota’s COVID-19 cases. Bars and restaurants were closed once again, despite being linked to just 1.7 percent of COVID-19 cases diagnosed since June 10.

Walz waffled when questioned on this. “I think this really does come down to, like so much of it, it’s not numbers, it’s not data…um…it’s neighborliness, and it’s about we’re all in this together,” he said. Things were no clearer three months on. When asked on Feb. 11 to outline the metrics he was using to make his decisions, he couldn’t answer. “If it was as easy as saying, if this hits this, we automatically do it — it’s a combination of things,” he said.

The second surge began to ebb. For the seven days up to and including Jan. 4, an average of 1,841 new cases were diagnosed daily, down from the peak of Nov. 13 — seven days before the shutdowns went into effect.

This fact didn’t stop state government officials from taking credit for the declining numbers. “We’ve seen the impact of the dial-back process and policies that the governor put in place and Minnesotans have worked hard to follow and make good decisions,” said Health Commissioner Jan Malcolm, the day before Ehresmann chided Minnesotans for their lack of obedience. She added that the second shutdown “clearly helped to change the pandemic’s trajectory this fall and safe lives.”

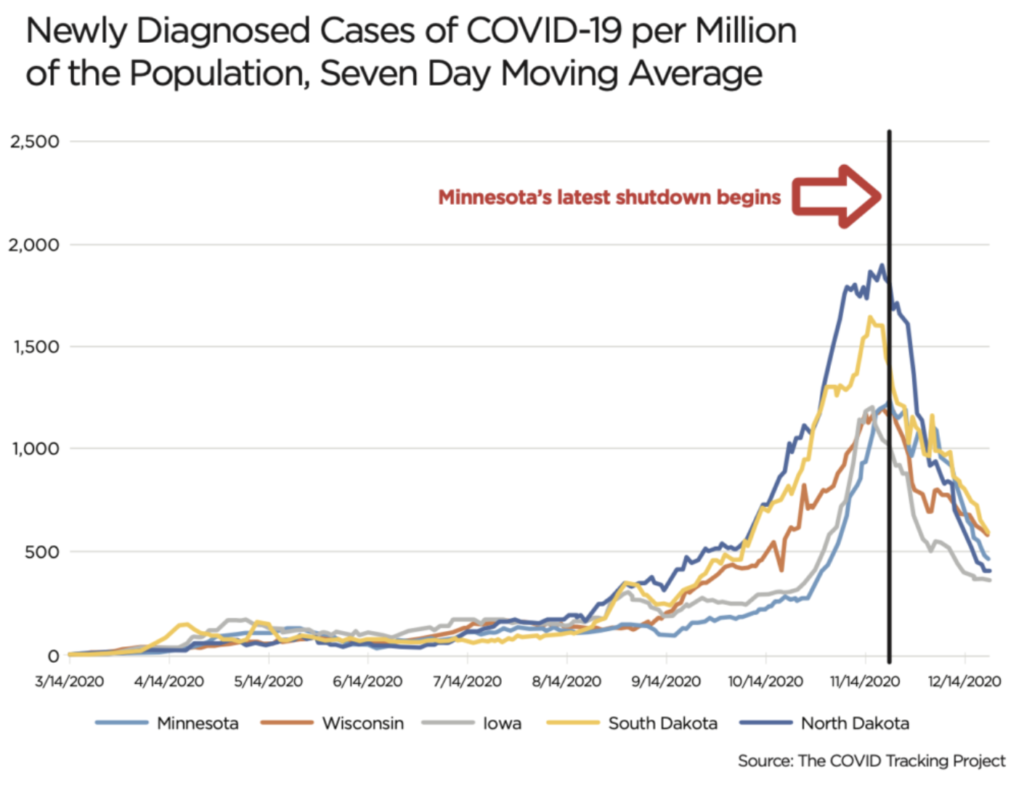

But apart from the timing, there was other evidence to suggest that Walz’s policies had little impact on the course of COVID-19: the record in Minnesota’s neighbors. Their patterns matched ours. As the chart shows, there is a marked upward surge in the rate of new cases between mid-August and mid-September, peaking in mid-November, before falling away rapidly thereafter.

This is despite the various policies pursued by these states. On mask mandates, for example, Minnesota has had one in place since July 25, Wisconsin since Aug. 1, North Dakota since Nov. 14, Iowa since Nov. 17, and South Dakota not at all. On shutdowns, The New York Times noted that businesses were “mostly open” in all of Minnesota’s neighbors with our state the only one of the five where they are “mostly closed.” Yet the patterns are the same. Is all this just incredible coincidence? Was Walz’s second shutdown such a potent weapon that it reduced COVID-19 numbers in neighboring states

too? Or is there some other factor at work?

Walz’s state of emergency, one year later

March 13 was the first anniversary of Walz assuming emergency powers to govern Minnesota by diktat. March 25 commemorates him telling us to “buckle it up for a few more weeks.”

Walz shut down the state to slow the spread of COVID-19 and build up ICU capacity. But when the peak hit, that ICU capacity was nowhere to be found. He initiated a Five-Point Plan for care homes, but care home deaths increased. He imposed a mask mandate to choke off COVID-19, followed, four months later, by the peak of the pandemic.

There is a lot of counting during a crisis like this — deaths, ICU beds and an unfathomable number of hours being locked in our homes, among others. But more than those statistics, the data prove something bigger, something more ominous. During a calamity, you can’t count on Tim Walz.