Employee freedom

Why ‘affirmative consent’ will be the new Freedom battleground to end forced unionism.

Center of the American Experiment launched the Employee Freedom Project in November 2015 to help free public employees from forced unionism and end the dominance of public-sector unions in setting state policies. Our motivation was that it is hard to make progress on education, pension reform, and other issues when public employees are required by law to fill the coffers of Education Minnesota, AFSCME Council 5, the SEIU and AFL-CIO, all well-oiled political machines masquerading as collective bargaining agents.

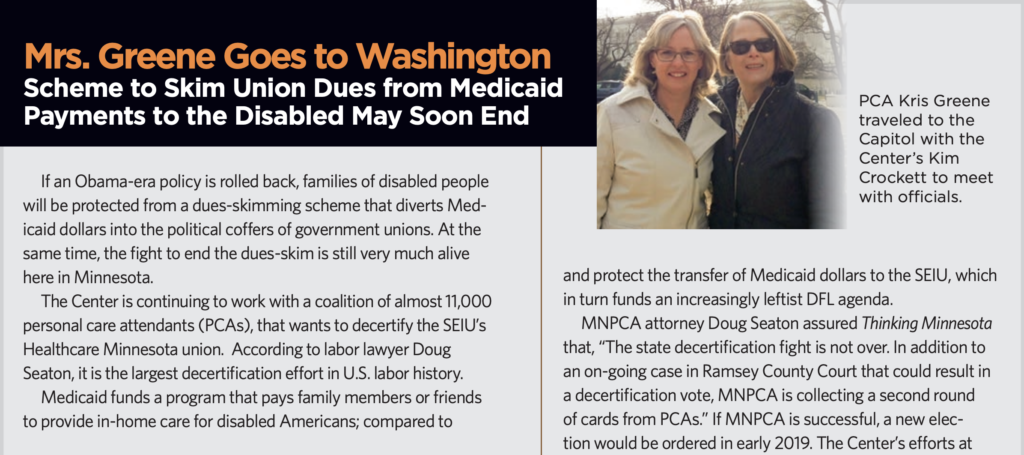

Since the project’s launch, the Center helped defeat certification of a union preying on child care providers for poor families, is working to decertify a union that skims dues from Medicaid benefits for the disabled (see sidebar nearby), and is educating public employees on their constitutional right to take a job without funding the union’s political agenda (which was restored by the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Janus v. AFSCME). As we look ahead to the 2019- 2020 legislative session, we have some bold ideas that would enforce Janus and expand employee freedom.

The Center wants citizens to understand that unions often thwart bi-partisan policy proposals that have little, if anything, to do with employee compensation or work rules—and the unions do it by leveraging the paychecks of our fellow citizens who work as public employees.

The unions effectively use the rhetoric and symbols of class warfare (e.g., raised fists) to keep employees anxious and dependent on the union. This makes us all feel more divided than we really are.

For over forty years, unions have enjoyed a position of power not occupied by any other player in our representative democracy. Once certified, they are the exclusive representative for all employees in a bargaining unit, even employees who choose not to join the union. As such, they take a cut of every employee’s paycheck. And the kicker is that the government collects the dues, even PAC money, for the union. Under Minnesota labor law, unions are not required to stand for recertification; and it is nearly impossible for employees to decertify a union once it is in place. That is why we call them “government unions.”

Think about the billions of dollars that have flowed into the coffers of government unions since the 1960s. How has that funding shaped and warped our political process? The Supreme Court held in 1977 that forcing public employees to fund a union as a condition of employment did not violate the Constitution. The Court had naively concluded that explicit political activities could be distinguished from collective bargaining and that unions could be trusted to fairly charge non-members just for the cost of representing them. The Court acknowledged in the Janus case last June that the distinction is unworkable, ruling that everything unions do is political speech, and that citizens who work in the public sector cannot be forced to fund it.

Public-sector union money invariably flows to one political party and an increasingly radical, openly socialist agenda that interprets policies through the divisive lens of race, gender and class. If you doubt this assertion, visit the website of any government union. You will find advocacy for open borders, voting rights for illegal aliens and socialized healthcare. Think about what has happened to our electoral politics, the size of government and our culture since 1971. Think about what has happened to the Democratic party since 1971. Would Hubert Humphrey recognize it?

It is therefore hard to overstate the importance of Janus v. AFSCME to our constitutional Republic and democratic process. While most employees are not rushing for the exits, the Court’s long-anticipated decision had immediate financial consequences for unions and, over time, will reduce the power of government unions and force them to focus more on actual representation of members and less on politics.

Across Minnesota, government employers stopped deducting “fair-share” fees from the paychecks of employees who had exercised their long-standing, constitutional right not to join the union. These so-called “fair-share” fees were anything but “fair” at 85 percent of full union dues, which for teachers can be over a thousand dollars a year. Those fees, now illegal, were essentially a forced contribution to the DFL.

The Center estimates that union revenue will fall about $10 million over the next year in Minnesota alone. For example, Education Minnesota reported in 2017 that 6,534 educators paid fair-share fees, representing an estimated $5.3 million in lost revenue. (We deal in estimates because unions are not subject to detailed disclosure laws on finances, but federal filings should reveal the impact on membership.) Over the next five years, we expect that 20 to 25 percent of public employees will resign from union membership, and that fewer new employees will join as the Janus decision changes the default from nearly automatic union membership to having a choice.

Here is the Court on Janus: “The idea of public-sector unionization and agency fees would astound those who framed and ratified the Bill of Rights. … We do know … that prominent members of the founding generation condemned laws requiring public employees to affirm or support beliefs with which they disagreed. … Jefferson denounced compelled support for such beliefs as ‘sinful and tyrannical’ …”

Private-sector unionism, which bargains over profits, peaked in 1966 at about 35 percent of Minnesota’s private workforce. It has now shrunk to about six percent. Most workplaces are safe and the perceived utility of paying a union has shrunk dramatically. By contrast, public-sector unionism, which became legal in Minnesota in 1971, bargains over taxes. It continues to grow even though most employees work in an office and get pay and benefits that are comparable to, or exceed, the private sector. (They will never hear that from the union.) In Minnesota, about 98 percent of 34,000 state employees are represented by a union. The municipal public workforce, including K-12 schools, has about 250,000 employees, and one of the highest rates of unionization in the nation, at 54 percent.

Fair-share payers like Mark Janus and Rebecca Friedrichs, who took their legal argument all the way to the Supreme Court, got an immediate pay raise in June. But more importantly, their First Amendment rights were recognized for the first time in their public careers.

But how did the Janus decision help employees who belong to the union? The Court made it clear that employers and unions had to have the affirmative consent of employees before dues are deducted from paychecks. Justice Joseph Alito, writing for the majority, said, “States and public-sector unions may no longer extract agency fees from nonconsenting employees,” and “[n]either an agency fee nor any other payment to the union may be deducted from a nonmember’s wages, nor may any other attempt be made to collect such a payment, unless the employee affirmatively consents to pay.” The decision establishes an opt-in procedure for “nonmembers … waiving their First Amendment rights, and such a waiver cannot be presumed.” (Emphasis added) Further, Justice Alito wrote, “Rather, to be effective, the waiver must be freely given and shown by ‘clear and compelling’ evidence.”

Using this language, the Court shouts a warning to unions and employers to end business as usual. The Court has flipped the default from a model where employees “opt-out” of the union to a model where employees must “opt-in” to the union.

The practical consequences are being litigated. The unions argue that Janus affects only employees who did not belong to the union as of June 27, 2018 and they are blocking the exits from union members who want to leave. Legal scholars and policy shops around the country, including the Center, argue that employers should immediately end the deduction of union dues until they have clear written consent from employees. To do otherwise is to risk future liability, putting taxpayers at risk of paying legal bills and settlements.

Employees who have previously signed a union card cannot be presumed to have freely given their consent. Moreover, the terms of membership laid out by unions do not meet the strict scrutiny required by the First Amendment.

First, employees who signed union cards before Janus were giving up a First Amendment right they did not know they had (the right not to fund the union’s political speech). Any union card signed before June 27, 2018 is, therefore, not a valid waiver of that right.

Second, this is the “choice” employees were given: if they did not join the union, they still had to pay 85 percent of dues to (allegedly) cover just the cost of collective bargaining, and even though they paid for bargaining, they lost the right to vote on a contract. On top of that, they lost all membership benefits like liability coverage and other perks, but they still had to accept whatever the union negotiated on their behalf because the union is their exclusive representative. And then there is union intimidation. One teacher told the Center when she refused to join the union, two union reps followed her into the hall, one on each side, harassing her like mean girls in sixth grade. Some call that choice; we call it duress.

Finally, union cards, which are not negotiable, authorize the deduction of dues (including PAC money) and set the conditions for resigning from membership. The union card for Education Minnesota, for example, states that a resignation can be submitted only during a narrow seven-day window once a year (this year it is September 24-30). (Learn more at EducatedTeachersMN.com)

If you are represented by AFSCME or the SEIU, the narrow window for resigning is usually based on the anniversary date of when you signed the card. Some cards even attempt to block resignations for several years at a time. We call these “Hotel California” cards. You can check in, but you can never leave.

Interpreting what the High Court meant by “affirmative consent” will be the battle ground for the next several years. Lawsuits have been filed in Minnesota and around the country on behalf of employees who are union members and agency fee payers. The exclusive representational status that unions now enjoy as a matter of law will, too, be challenged. These issues will play out in the courts and state legislatures all over the country. And the Center is delighted to be in the middle of it all.

The Employee Freedom Project has accomplished a great deal since its launch. In addition to our work on the Janus case, the Center has challenged the expansion of government unions into home-based care funded by Medicaid. We estimate unions were skimming about $200 million annually from Medicaid programs for low-income parents and the disabled in eleven “blue” states. We are confident union revenues are down and the legal bills are up due to the Center’s efforts and our national partners. Even better, more Medicaid dollars are going to the intended beneficiaries rather than government unions.

What is next? In addition to educating employees about their Janus rights, the Center looks forward to introducing lawmakers to several ideas that would enforce Janus and expand employee freedom. For example, the state should immediately end the practice of collecting union dues, require unions to collect PAC money separately from dues, and post a “Janus Rights Notice” in all government workplaces.

No one expects all this to be the end of public-sector unionism in Minnesota. In the short term, we could see increased labor unrest and a lot of angry union rhetoric, but over time, as unions, employees and elected officials adjust, our public sector should be more, not less, civil. A Janus win could usher in healthier public-sector unionism if enough employees exercise their rights, and if union leaders treat members as customers to be served instead of taking them, and their money, for granted.

About the Author: Kim Crockett is vice president and senior policy fellow at Center of the American Experiment. She is a co-director of EducatedTeachersMN.com, an online resource for teachers in Minnesota.