Hennepin County’s success

The county’s effective use of resources for the mentally ill and chemical dependent is a cause for celebration.

“The conservative fosters the fullness of human potential by protecting the freedom and dignity of each person, acknowledging that responsibility comes with freedom. Rights and duties are always linked.

For the conservative, each man and woman is equal in dignity and equal before the law, but gloriously individual and unequal in talents, aptitudes, and outcomes. The conservative celebrates the uniqueness of individuals and does not level to eliminate differences.”

Barbara J. Elliott,

The Conservative Credo

One of the intangible benefits of a period of low crime is how it can parlay into greater public safety results by allowing system practitioners time to identify and resolve more complex problems. This was the case in the mid-2010s when a period of relative calm allowed public safety, public health, and criminal justice leaders the time to collaborate on solutions to a decades old dilemma of how to better serve the mentally ill and chemically dependent (MI/CD).

Up to that point, millions of dollars had been spent on criminal justice and emergency medical resources on a cohort that in the end wasn’t being well-served by either. This poor public policy was arguably leaving people trapped in a cycle of social failure.

This is the story of an initiative in Hennepin County designed to divert MI/CD people from traditional criminal justice system and emergency room dead-ends toward more appropriate pathways that are not only more humane, but are far more efficient and effective in addressing the challenges facing those caught in the system. These initiatives align well with traditional conservative values that ensure resources are used wisely and are designed in a manner that values the opportunity for redemption.

The problem of limited options

Historically, one of the only options for police faced with a MI/CD person committing a low level “crime of survival” (such as trespassing due to homelessness, or petty theft due to indigency, hunger, or chemical dependency) was to book them in jail.

While it was technically correct because the person was committing a crime, it was a poor solution that diverted criminal justice system resources away from serious crimes simply to deal with the churn of low-level misdemeanors — and it failed to connect MI/CD defendants to resources that could provide long term solutions to their problems and break a cycle of self-destruction.

Far too often an arrest for a low-level misdemeanor resulted in the person being booked and released with a court date, the person failing to respond to that court date, and a series of bench warrants and re-arrests before the person’s case was resolved. Informal court studies showed that a single arrest of an MI/CD person for a low-level misdemeanor would often result in at least two more arrests for — failure to appear — before the case was finally resolved in court. The tragic consequence was after all of this, the MI/CD person was no better equipped with the tools needed to avoid another encounter with law enforcement, and now had a criminal record or a warrant added to their situation.

The other option for first responders when they encountered this cohort was to bring them to Hennepin County Medical Center’s (HCMC) emergency room for medical care. This served only to clog the ER with non-emergency patients and used thousands of dollars in finite Emergency Department resources for unwarranted, non-emergency issues. The ER was not designed as a low-level MI/CD resource center. The only practicable response was to make an evaluation for emergency medical issues and then discharge the patient with no real expectation for appropriate follow-up care.

Both options were poor. They were inefficient, ineffective, and too often left the MI/CD in a downward spiral instead of providing the helping hand they needed. It was an appropriate moment for government to step up and create public policy that broke the destructive cycle.

Opportunity knocked

A combination of pro-active policing and effective punishment beginning in the mid-1990s helped drive Minnesota’s crime down for over 20 years. By 2015, crime was manageable and resources were healthy such that law enforcement, criminal justice, and human services and public health leadership began looking at making an impact in areas that had been previously out of reach.

Hennepin County’s plan

In 2015 there was growing recognition and concern for the number of mentally ill and chemically dependent inmates in jails. The Minnesota Legislative Auditor and the Major County Sheriff’s Association were studying the issue of mental illness in jails. The Hennepin County Sheriff’s Office conducted a one-day snapshot study of inmates in its custody and determined that 52 percent of inmates had a history of mental illness. Also, as mental health treatment facilities closed or filled, county jails became the de facto mental healthcare system for far too many people. Many sheriffs began speaking out about the issue. Sheriff Rich Stanek told the Star Tribune in 2016, “What we’re seeing is crisis levels of mental illness among our inmates. This is solid evidence that our jails continue to serve as the largest mental health facilities in the state.”

In response to these concerns, the Hennepin County Board committed itself to reducing the number of people with mental illness in the jails. It was part of the Stepping Up Initiative supported by the National Council of Counties. The board’s resolution acknowledged the following facts:

- Prevalence rates of serious mental illnesses in jails are three to six times higher than for the general population.

- Almost three-quarters of adults with serious mental illnesses in jails have co-occurring substance use disorders.

- Adults with mental illnesses tend to stay longer in jail and upon release are at a higher risk of recidivism than people without these disorders.

- County jails spend two to three times more on adults with mental illnesses that require interventions compared to those without these treatment needs.

Without the appropriate treatment and services, people with mental illnesses continue to cycle through the criminal justice system, often resulting in tragic outcomes for these individuals and their families.

Hennepin County’s response

As a result of this focused concern, Hennepin County’s Criminal Justice Coordinating Committee formed a Behavioral Health Sub-Committee (BHSC) and tasked this sub-committee with researching and proposing solutions to problems involving MI/CD people who enter the justice system. The BHSC was made up of representatives from public health and human services, the county and city attorney’s offices, the public defender, district court, and law enforcement, and began meeting regularly.

I was the sheriff’s office representative on this sub-committee, and together with my new colleagues, set about to collaborate on ways to improve outcomes for MI/CD individuals. This not only represented fiscal responsibility, but also represented a pathway to help improve their lives by connecting them with sustained resources and programs designed for their situations and also to avoid jail.

The BHSC began with a thorough review of existing processes our agencies used when encountering the MI/CD population to identify areas for improved outcomes. We also conducted reviews of several other jurisdictions to see how they were dealing with this cohort.

We visited jails, courts, and medical facilities in Chicago, Orlando, Houston, Los Angeles, and New York City to meet with our counterparts and learn from their efforts at early identification of MI/CD and about diverting that cohort away from the criminal justice system and emergency rooms where appropriate.

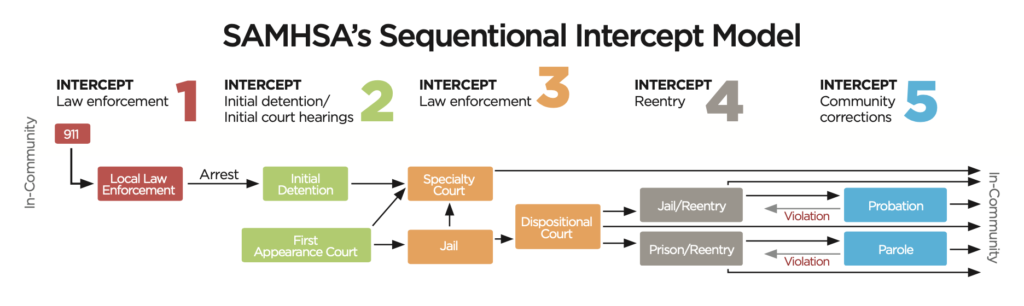

Based on what we learned, our group committed to the concept of developing a coordinated response around the Sequential Intercept Model (SIM) as developed by the Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), an agency within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

SIM identifies all the potential contact points a person has in the criminal justice system and offers opportunities to “intercept” or divert that person from the standard process. It provides alternative resources to the situation to offer a better outcome for the MI/CD and is shown in the chart below.

Intercept One — jail diversion

The first and arguably most impactful intercept point is the initial call and response by law enforcement. It became immediately clear to us that our priority for officers should be to develop alternatives to jail for MI/CD individuals who commit “crimes of survival.” This also included alternatives to hospital emergency rooms.

To address possible Intercept One opportunities, the BHSC decided on the concept of a walk-in/drop-off behavioral health center where the MI/CD cohort could either self-report or be dropped off by first responders or others. It represented an appropriate intercept and offered first responders a resource other than jail or the ER for these low-level offenders. Officers maintained discretion on whether to submit a case to the prosecutor’s office for charging consideration, however that was not the goal of the intercept.

In 2018 Hennepin County Human Services and Public Health developed a plan to re-envision and retrofit the old county detox center at 1800 Chicago Ave. S. in Minneapolis based on the walk-in/drop-off model that included the creation of a comprehensive Behavioral Health Center (BHC). This center operates as triage and assessment clinic that connects those dropped off with sustained resources to help them with their MI/CD issues. This center serves as a jail diversion option for officers dealing with MI/CD individuals who don’t pose a public safety threat and are not in need of hospital-level care. The BHC also has a 16-bed unit dedicated to crisis stabilization and a 60-bed unit for substance abuse withdrawal.

The renovation costs to open the center totaled just over $7 million — much of it covered by a state grant. The annual operating budget has been set at $1 million in 2022 and $1.8 million in 2023.

As of April 2022, the walk-in/drop-off center is open 9 am to 9 pm, Monday through Friday, with the goal of becoming a 24-hour, 7 days per week resource once staffing and funding are secured.

In 2020, the clients served by the center averaged about 175 per month. As of September 2022, the average has risen to over 600 per month — a testament to both the need for and the utility of the center.

Other Intercept One initiatives include Crisis Intervention Training for officers, deputies, and dispatchers. This training helps dispatchers identify possible MI/CD issues and determine the best responses. For law enforcement, it provides tools to recognize MI/CD behaviors and to utilize responses that improve compliance, reducing the need to use force. It also incorporates social workers into police departments to assist officers and to follow-up with individuals who would benefit from other resources.

Intercepts 2-5

These intercepts have been addressed largely through the Hennepin County Jail’s Mental Health Initiative and the efforts of the Hennepin County Treatment Courts, Human Services and Public Health, and Community Corrections.

The Hennepin County Sheriff’s Office implemented several changes in how it staffed and managed the MI/CD people in custody. These efforts were monitored and refined continuously during a purpose-driven weekly staff meeting I chaired as the Jail Commander. Members of the team included the jail nursing manager, the mental health nurse, the release nurse, a human services manager, and deputies assigned to various posts such as mental health units, release, and classification.

This group worked diligently to create a system that focused on early identification of the MI/CD individuals who were booked, routing them to jail medical for evaluation, and classifying them to ensure they were managed properly during their detention.

An important part of the system was the addition of a “release nurse” who reviewed the pending releases and ensured they had future appointments, prescriptions, and active medical issues in check before being released. Prior to the release nurse position, inmates were too often released without being given information on future social services appointments or their medications and prescriptions. The situation for these people frequently deteriorated because of this disconnect, and the cycle of re-arrest or admission into the emergency room repeated.

One of the most successful aspects of the jail initiative was the collaboration with Human Services and Public Health (HSPHD) to embed social workers in the jail. This team was named the Integrated Access Team (IAT). The IAT reviewed each booking to determine if the arrested party was a current or former client of a county social worker. If so, they would re-connect and ensure resources and programming didn’t become derailed due to the arrest. If the person wasn’t connected to social services, the IAT met with the individual, evaluated his needs, and set up a plan for access to resources to ensure future success.

The team of deputies, IAT, and jail medical made certain that court party notifications were made when a current or former mental health court client was booked into jail. This allowed for prompt review of the situation by the parties and the judge, and ensured quicker decisions on continued detention, appropriate charges or diversion, requests for competency evaluations, or even the transfer to HCMC or another regional mental health facility. This coordinated communication helped facilitate court interception of MI/CD criminal cases and avoided repeated releases and re-bookings for the same offence.

All of this was done without diverting funding away from law enforcement. Each of these intercepts repurposed existing resources to target them more specifically to the MI/CD frequenting jails and emergency rooms.

Results

The initiatives implemented since 2015 have shown great success. While COVID and the civil unrest after the death of George Floyd disrupted and delayed some of this work, the results have nonetheless been impressive.

Data compiled by the jail’s IAT indicates the team of social workers embedded in the jail and connecting with the MI/CD cohort is having a significant impact in reducing future arrests and use of emergency room resources. In 2017 for example, those inmates who connected with the IAT experienced an impressive 92.5 percent reduction in jail bookings and a 24 percent reduction in emergency room admissions in the 12 months following their acceptance of IAT resources.

The Behavioral Health Center’s walk-in/drop-off center conducted an analysis of the clients using the center between January 1, 2020, and June 30, 2021, comparing the six months before using the resource with the six months after. The clientele experienced a 14 percent reduction in both jail bookings and emergency room visits.

Given the thousands of individuals that are now serviced through the IAT and BHC annually, the financial savings achieved through reductions in the number of jail bookings and use of emergency room resources is conservatively several million dollars per year. Hennepin County plans to conduct a robust Return on Investment (ROI) study in the coming years. The human successes are arguably more impactful and important than the financial savings. Helping the MI/CD population by breaking the cycle of unnecessary arrests and prosecutions not only benefits them, but greatly benefits the criminal justice system by reducing caseloads and allowing the system to focus resources on serious crimes.

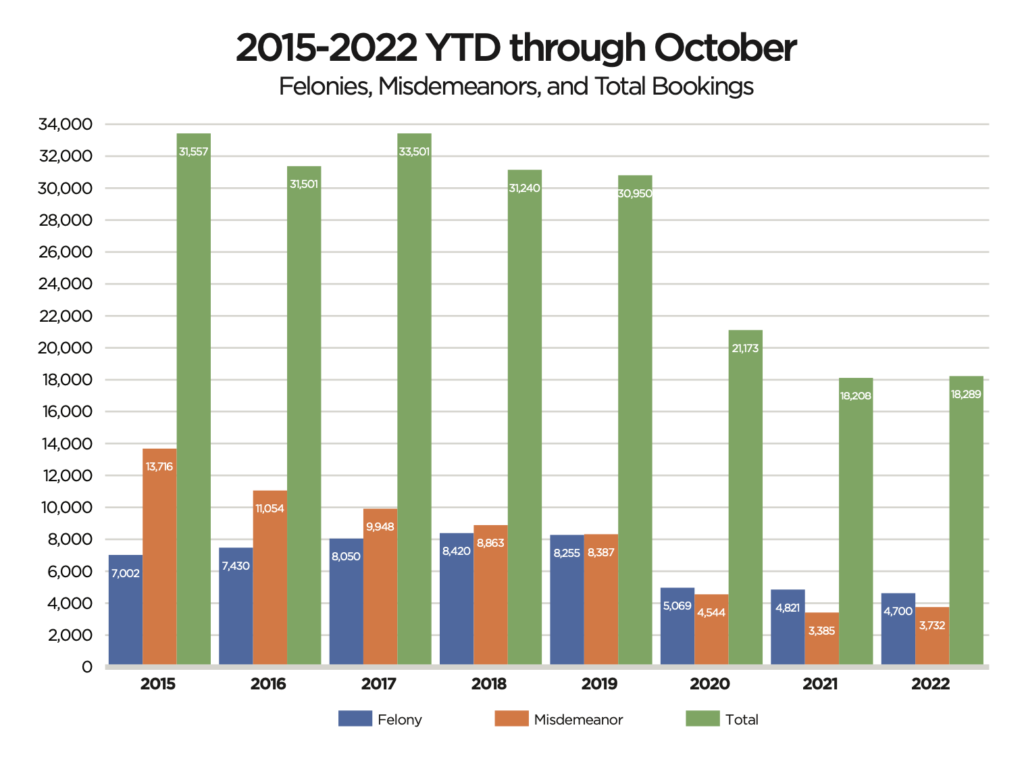

The adjacent chart illustrates the change in the proportion of low-level misdemeanors to serious felony bookings since 2015 in the Hennepin County Jail. While COVID and civil unrest since 2020 have certainly played a part, intercepting low-level offenses involving MI/CD people have flipped the ratio to where felony bookings now outpace misdemeanor bookings. This contrasts sharply to 2015 when misdemeanors outnumbered felonies 2-to-1.

Conclusion

In 2015 during a period of relative calm, Hennepin County leadership recognized and began addressing a long-standing problem: system practitioners using the jail and emergency rooms to deal with mentally ill and chemically dependent behavior. Hennepin County has devoted a considerable amount of effort and repurposed many resources to deal more effectively with the issues confronting the MI/CD population.

The efforts are paying off financially for the taxpayers who ultimately fund the efforts, and more importantly for the MI/CD individuals who are directly impacted, as well as others in the community. In the Hennepin County Criminal Justice Behavioral Health Initiative’s five-year report from October 2020, Mary Ellen Heng, Deputy Minneapolis City Attorney recalled this success story:

“A woman I have prosecuted for many years for DWI and prostitution has addiction issues that drive her behavior. She has been in and out of treatment and jail. She started using again and was convicted of gross misdemeanor trespassing.

When she successfully completed Restorative Court, she was nine months sober, had her own place to live and had no new offenses since engaging with the social workers. By all accounts she is a success story, and she is staying on this good path.”

An era of low crime provided an opening to find ways to alleviate the chronic dual problems of failing those with mental health and chemical dependency issues and diverting limited emergency and law enforcement resources from serious crimes. Hennepin County found success in these new strategies creating more humane, efficient, and effective solutions, and we all reap the benefits.