Minnesota’s demographic challenge

Why Minnesota may lose a congressional seat after the 2020 Census even with metro growth

A preliminary report from the Metropolitan Council estimating the current population, says the seven-county metro area grew by 191,628 residents between 2010 and 2016.

Minnesota’s State Demographer, Susan Brower, confirms that there has indeed been a notable uptick in the number of residents in the metro area and two core cities. Nevertheless she says Minnesota’s population in relation to other states is declining. That could mean one less seat in Congress. Brower says: “The loss of Minnesota’s eighth Congressional seat is a real possibility, but it is not a foregone conclusion.”

What is going on demographically? Out of the 5.49 million people in the state, almost half a million were born outside of the United States. Moreover, people from Minnesota are leaving, and people from the U.S. are not moving here in sufficient numbers to reverse the trend. In fact, the state’s net-positive growth is from foreign-born residents.

I recommend you visit the State Demographer’s website for detailed reports on how Minnesota is growing—and how Minnesota is declining, demographically speaking. A short report called “Ada to Zumbrota” explains the state’s demographic trends:

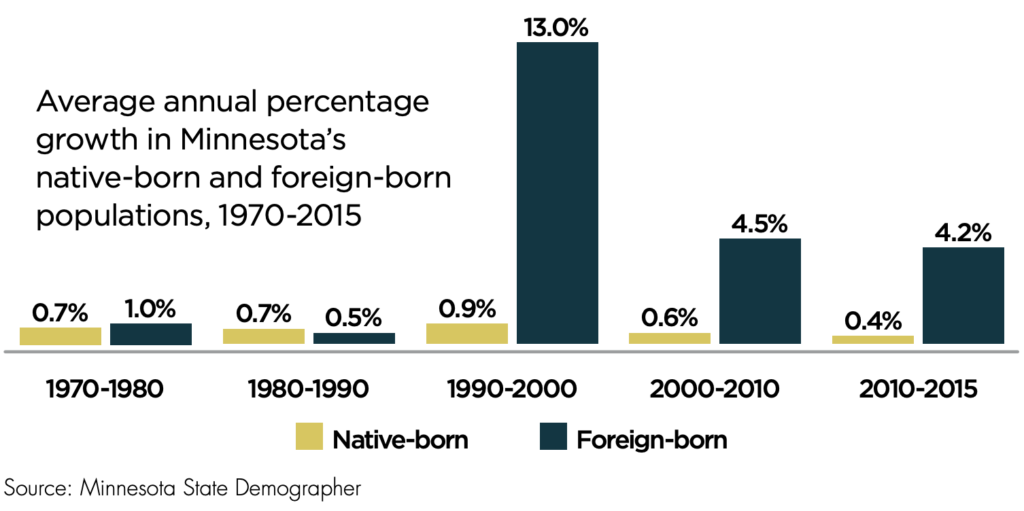

While both the U.S.-born population and foreign-born population have grown since 1970, the foreign-born population has swelled more quickly….Minnesota had about 113,000 foreign-born residents in 1990, but that number had more than quadrupled to about 457,200 residents by 2015.

Some of that growth is from refugees placed here by the State Department. Since 1979, Minnesota has welcomed approximately 105,000 refugee placements. Minnesota is also a top destination for the secondary migration of refugees from other states.

The net change for Minnesota’s foreign-born population between 1990 and 2000 alone was 13% annually. By comparison, population growth due to natural increase in Minnesota was less than 1% annually during those same years.

Since 2002, Minnesota has maintained consistent annual domestic out-migration—that is, more people moving out of Minnesota to other states than people moving into Minnesota from other states. The most recent year of data, 2015, shows that Minnesota had about 13,700 (net) international migrants and about —1,800 (net) domestic migrants. In sum, our international arrivals rescued us from experiencing negative overall migration, resulting in a total (net) migration of about 11,900 arrivals in 2015.

My colleague Peter Nelson’s work on income migration demonstrates that we are losing taxable income and wealth to other states. Minnesota is saying goodbye to taxpayers, and hello to new residents, most of whom are just making their way up the income and tax ladder, and many of whom are dependent on welfare. In other words, we are decreasing the revenue base while increasing the demand for government services.

State trends do not tell us what is driving population growth in the metro area but it seems reasonable to assume that foreign-born residents, especially refugees, are residing in the metro at least initially (due to refugee placement agencies, social services, subsidized housing, jobs and most of all, the presence of kin).

It is no surprise that Minnesota continues to be attractive to immigrants of all kinds. Who would not want to live here, given our liberty, prosperity, tolerant culture and generous welfare state (no jokes about the weather, please). Minnesota is more Swedish than Sweden when it comes to welcoming immigrants.

But why is Minnesota unable to retain and grow its domestic population—or to attract more people from around the U.S., to the point where a congressional seat is at risk? Could it be that the very policies that make Minnesota so attractive to immigrants, such as those championed by the Met Council, make the state increasingly unattractive to taxpaying Minnesotans?

We have less than three years to turn this around before the 2020 Census. The clock is ticking.