Misunderstanding inflation

‘You may not be interested in monetary economics, but monetary economics is interested in you.’

The Biden administration is working through the stages of grief when it comes to inflation. In July, President Biden said that “no serious economist” was worried about “unchecked inflation.” In October, with inflation still stubbornly high and rising, White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki said that inflation was actually a “good thing” because it showed the strength of the economy’s recovery from the COVID-19 shutdown. In November inflation was no longer a good thing, and the Federal Trade Commission was investigating Walmart, Amazon, Kroger, other large wholesalers, and suppliers including Procter & Gamble Co., Tyson Foods, and Kraft Heinz Co. “to turn over information to help study causes of empty shelves and sky-high prices.”

John Maynard Keynes once wrote, quoting Lenin, that “not one man in a million” understood the mechanics of inflation. Whoever that one man is, he clearly doesn’t work for the Biden administration. But with prices up 6.2 percent in the year to October, “the largest 12-month increase since the period ending November 1990” according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, Minnesotans cannot afford to remain as ignorant.

Put very simply, the price level, measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI), is the amount of money spent in a given period divided by the amount of stuff (goods and services) bought in a given period. If the amount of money spent increases faster than the amount of stuff bought, that ratio increases, inflation, in other words.

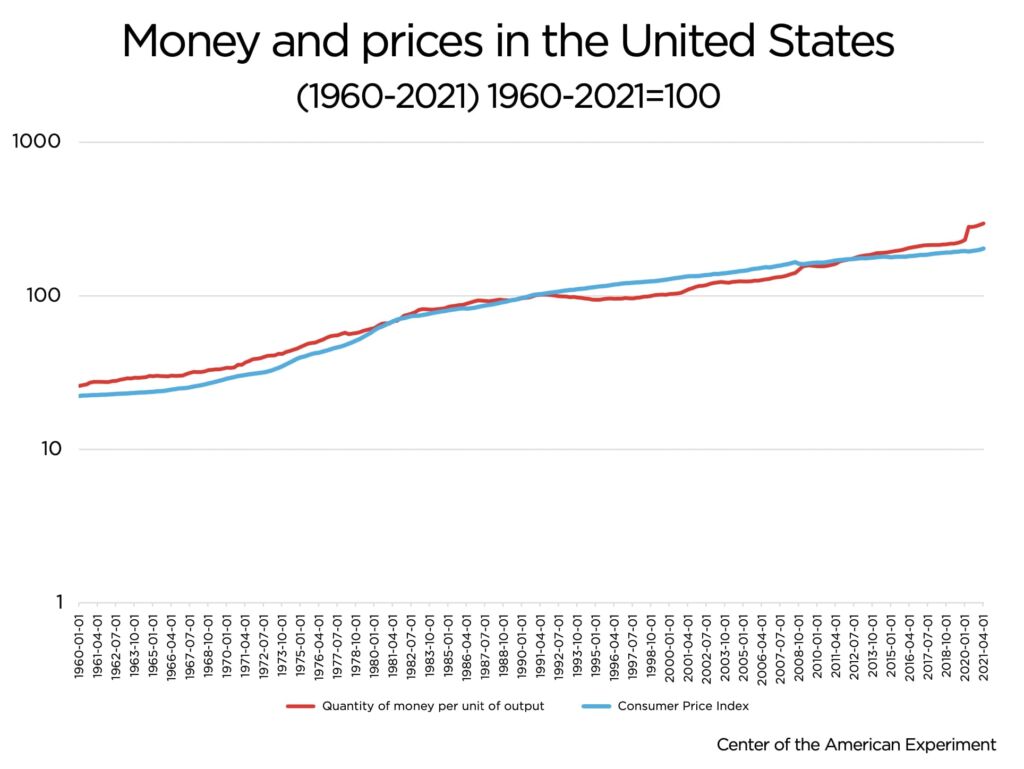

This is borne out by the close relationship over several decades between the quantity of money per unit of output – a measure of money divided by stuff – and the CPI – a measure of inflation (both series are expressed as percentages of their average values over the period as a whole to make them comparable and the Y axis is logarithmic).

The right side of the nearby chart shows a sharp, recent jump in the quantity of money per unit of output. This is driven by a 37 percent increase in the M2 (money stock measure) money supply between January 2020 and October 2021 while Real GDP – a measure of stuff – increased by just 2 percent between Q1 2020 and Q2 2021. If people had been willing to hold on to this cash it wouldn’t have been inflationary, but they spent a good chunk of it. In the 16 months from June 2020 to October 2021, Personal Consumption Expenditures increased by a monthly average rate of 1.0 percent compared to an average of 0.3 percent for the 16 months from October 2018 to February 2020. This is where our current inflation comes from.

What happens next? If the two lines on our chart are to converge and reestablish their historical relationship, then one or a mixture of three things needs to happen:

- A decline in the quantity of money (affecting the red line)

- An increase in Real GDP (affecting the red line)

- An increase in the CPI (affecting the blue line)

A decline in the quantity of money necessary to bring the two lines together is unlikely. Going back to at least 1960, the M2 money supply has never fallen year over year, and it continues to increase at rates well above historical trends. In no single month between November 1983 and April 2020 did the M2 money supply increase at double digit monthly rates: it hasn’t increased at a single digit rate in any month since. GDP growth is also slowing back to historical rates after the initial snapback as economies reopened late last year. That leaves the CPI to do most of the work to bring these two lines back together – if the red line won’t fall, the blue line will have to rise – and that means more inflation.

What can be done about this? The Federal Reserve ought to slow its money creation. The federal government should pursue supply side policies to increase the amount of stuff and it should abandon plans to dump trillions of dollars of spending into the economy. Sadly, the prospects for any of this happening – and, hence, of our outlook for slowing inflation – are not good. To paraphrase another Bolshevik, “You may not be interested in monetary economics, but monetary economics is interested in you.”