More Ted, less taxes

A lesson for state and local policymakers.

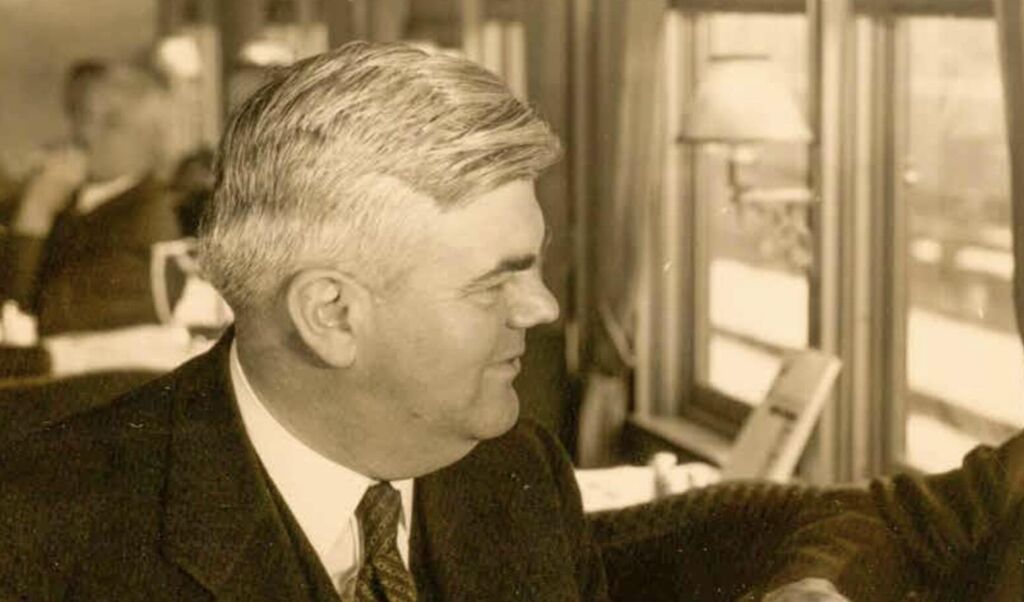

In presidential history, scholars place a higher value on American presidents who took an expansive view of their executive powers and increased the size and scope of government. As an example, President Franklin D. Roosevelt is usually ranked in the top five of our nation’s best presidents, while President Calvin Coolidge is ranked much lower. Roosevelt expanded government with his New Deal and used vast executive powers, while Coolidge did the opposite. The same is true when examining state governors. In Minnesota, the progressive Gov. Floyd B. Olson is viewed as a visionary, while little known Gov. Theodore Christianson is considered a conservative reactionary. But historian popularity contests don’t tell the whole story and Christianson deserves to be remembered as a conservative policy leader and should hold a place at the top of successful Minnesota governors.

A man of the times

Theodore Christianson was a lawyer, newspaper editor, and historian who wrote a five-volume history of Minnesota (Minnesota, The Land of Sky-Tinted Waters: A History of the State and Its People); he also served in the Minnesota Legislature. He was elected governor in 1924 and served three terms in that office. During his time in office Christianson made fiscal prudence, or “economy in government,” a priority. He campaigned on slogans such as “More Ted, Less Taxes” and was given the nickname “Tightwad Ted.” He described himself as a true “liberal” — that is, in the old-fashioned sense of the word. Later he would serve in the United States House of Representatives and was an unsuccessful candidate for United States Senate.

Christianson’s fiscal policies reflected those of Presidents Warren G. Harding and Calvin Coolidge. While Coolidge was cutting tax rates, reducing spending, and paying down the national debt at the federal level, Christianson was doing the same in Minnesota. In 1924, Christianson argued that the “demand for a halting of the increase in taxation and public indebtedness is making itself felt, not only in Minnesota, but throughout the nation.”

As a former legislator and chair of the Appropriations Committee, Christianson understood the budget and also the numerous special interests that were clamoring for more spending. He believed two of the largest economic policy problems consisted of reducing the tax burden and cutting spending.

Balancing fiscal and social issues

Although Christianson shared a similar belief in “economy in government” as Coolidge, he did have some progressive tendencies, especially when it came to agricultural policy. This was not uncommon for many Republicans from the Midwest. During a campaign speech in 1926, Christianson even described the Republican Party of Minnesota as a progressive party. Nevertheless, he was also concerned about the radicalism of the Farmer-Labor Party in Minnesota and the Nonpartisan League of North Dakota.

Governor Jacob Aall Ottesen Preus, who served in office prior to Christianson, spoke for many concerned Republicans that the Farmer-Labor Party and the Nonpartisan League represented dangerous ideas of “socialism — a political cult that would destroy the principles of private property, our religion, and our homes.” Further, in his farewell address to the legislature, Preus argued that “a large group of Republicans and Democrats” worked together to stop the establishment of “state socialism along the lines attempted before and since in North Dakota.”

Gov. Christianson reflected a conservatism that placed a priority on fiscal prudence and resisting the radical political philosophy of progressivism that was a growing force in the Midwest. Reducing the size and scope of government was a top priority. In 1924 he stated that “not only has there been a marked tendency toward too much government, but an undue enlargement of the personnel of government.” In his Inaugural Address, Christianson urged the Legislature to refrain from excessive spending in the state budget by following these six measures:

- We should authorize no new State activities and create no new State institutions.

- We should raise no salaries, except when it can be clearly shown that through salary increases it will be possible to obtain the services of administrative heads who can save their salaries through greater efficiency and economy of operation.

- We should authorize no construction not imperatively and immediately needed.

- We should create no new state obligations.

- We should make a careful survey of the administrative code to determine whether it would not be feasible to discontinue some of the State’s activities.

- We should not extend any new form of State aid to promote local activity, nor should we accept any new form of Federal aid conditioned on State expenditures.

These recommendations, or “principles,” were necessary for not just the fiscal health of Minnesota, but also protecting the interests of the taxpayer.

Veto power

Christianson understood the pressure to spend money, including the demand for more public infrastructure spending. Nevertheless, he argued that “there has been likewise a tendency toward making too many and too elaborate public improvements, improvements which, however desirable, are beyond what the people can afford.” He argued that the executive branch should have more power “to limit and prevent the expenditure of public money” and that both the governor and the legislature had a responsibility to control spending. Christianson stated, “The Legislature from time immemorial has been the taxpayer’s last line of defense. Its power to limit or withhold revenue it must not and cannot relinquish.” Although the Legislature often clashed with Christianson over his use of the veto it was successful in limiting spending.

As governor, Christianson was the first executive to use the veto power extensively to limit spending. During his 1926 campaign, he celebrated that his use of the veto in one year — 1925 — saved taxpayers over $1.8 million. During the 1929 legislative session, Christianson vetoed three appropriations that accounted for over $15 million. These are just a few examples of his vetoes which totaled 76 during his time in office saving taxpayers close to $18 million.

It is often argued that reducing spending was a lot easier during Christianson’s time because state government was smaller. However, this argument is false because Christianson, just as with Harding and Coolidge at the national level, had to fight to limit spending. Some of his vetoes were applied to education appropriations, which created anger. Cutting spending is never easy whether it is in the 1920s or 2023.

One of the major government reform initiatives that occurred under his watch was the 1925 Reorganization Act, which made the state government more efficient by limiting bureaucracy. Christianson argued that reforming state government by making it leaner was a good policy, but it was even more important in making it more difficult for government to spend taxpayer dollars. He stated that “it is not necessary to have three or four inspectors do the work that one can do,” adding, “It is not necessary to have 92 separate and distinct departments, boards, and bureaus operating in Minnesota when a smaller number would do as well.”

From Christianson’s perspective, government was not always the solution to every policy problem, “It is not necessary to create a new board or bureau to take care of every situation that can possibly arise especially in view of the fact that there are so many things that individuals can do so much better for themselves than any board or bureau can do for them.”

Relieving the burden

Since Minnesota at this time did not have an income tax and relied on property taxes and other taxes for government funds, Christianson argued that a fiscally conservative policy agenda should serve as an example for local governments to lower their property taxes. “Economy in state government should set an example for communities,” stated Christianson. The New York Times reported toward the end of his time in office that Christianson has made tax relief a “chief undertaking of his administration.” Like Coolidge, he argued that lowering taxes would benefit everyone in the economy. Christianson stated, “The best thing the State of Minnesota can do for the farmer, the laborer, or any other man, is to relieve him, so far as it may be done, of the burdens it has imposed on him. Reduce taxes, and farms will yield a larger net return. Reduce taxes, and the manufacturer can make goods and the merchant sell them at a lower price, and the laborer’s wage will have greater purchasing power.” Christianson advised the Minnesota Legislature not to be hasty in voting for legislation. “‘When in doubt, vote No,’ might well be emblazoned over the door of every legislative hall,” he stated, foreshadowing the advice of a future conservative, Senator Barry M. Goldwater.

Throughout his time in office, Christianson considered the “interests of the taxpayers as of higher value than the wishes of the tax-spenders.” The principles of lowering tax rates, reducing spending, reducing debt, and making state government more efficient are all policies that lead to making a state more competitive.

Christianson believed the question of taxes was more than just money. “There is more involved in the problem of taxation than the money which we as taxpayers must pay, there is involved nothing less than the perpetuity of our social order, for if the superstructure becomes too heavy for the human, civilization is doomed.” One wonders what he would think of Minnesota’s high tax rates today and a state government that has become a leviathan.

In our current era, Christianson seems obsolete. Fiscal conservatives in both political parties, especially at the national level, are an endangered species. Many would argue that society and our economy has grown too complex for a conservative philosophy of limited government to work. Progressives were of the same mindset during Christianson’s time in office. In 1924 he told Minnesotans that “getting government back to first principles is the biggest political task of the present generation.”

Lessons for today

The ideas of fiscal restraint are not obsolete. In fact, the spirit of “Christianson” is prevailing in states across the nation. The Tax Foundation reports that 43 states in 2021 and 2022 enacted tax reforms. This year more states are considering tax reforms. In fact, Minnesota could learn a lesson from their neighbors to the south in Iowa. Last year Gov. Kim Reynolds signed into law the most comprehensive state-based tax reform measure in the nation. Iowa’s progressive income tax is being replaced with a flat 3.9 percent income tax. The state is also reducing the corporate tax rate.

Reynolds has limited spending and earned the top grade from CATO Institute’s Fiscal Policy Report Card on America’s Governors. Since assuming office, she has kept General Fund spending at a low annual average rate of 2.3 percent. Reynolds has also made sure the priorities of government are properly funded. As a result of Iowa’s major tax reforms and prudent budgeting, the CATO Institute gave her the highest ranking in the nation, while Gov. Tim Walz received a failing grade for his taxand-spend agenda. During the current legislative session, Reynolds is also proposing to reign in Iowa’s administrative state. Currently, Iowa has 37 executive branch cabinet agencies, and she is proposing to reduce these agencies down to 16. Governor Reynolds has acknowledged that it is time to streamline state government and make it more efficient. Her plan is estimated to save taxpayers at least $215 million over the next four years. Reynolds, just as with Christianson, also wants local governments in Iowa to follow her example of reducing their budgets and providing tax relief. Finally, she has established the goal of eliminating Iowa’s income tax by the end of her term.

Iowa is just one of many states that are following a policy of fiscal conservatism. North Carolina is another example and for years has been the gold standard for state tax reform, demonstrating that tax rates and spending can be reduced without sacrificing the priorities of government.

But Minnesota exemplifies the dire consequences of turning away from a Christianson approach to fiscal policy. Progressive government in Minnesota is failing. The tax-and-spend agenda is not working. The state continues to lose population. Minnesota needs to follow the philosophy of Gov. Christianson and a “return to first principles.”

President Ronald Reagan made a symbolic gesture when he placed a portrait of Coolidge in the Cabinet Room of the White House. It is unlikely that Walz would ever place Christianson’s portrait in the executive office, but perhaps a future Minnesota governor would find inspiration from him.

Reporting on his death, The Washington Post wrote that Christianson was a “staunch Republican who devoted himself to curbing the mounting cost of state government and reducing state indebtedness.” Christianson, a champion of limited government in Minnesota, is an example for state and local policy leaders across the nation now. It would be wise to follow the path he laid forth to return the state to a land of prosperity and opportunity for which it was known during his time.