Never mind

The tone-deaf members of Minnesota’s Sentencing Guidelines Commission abandon their plan to reduce prison terms during our record spike in violent crime. At least for now.

After a cantankerous reaction by anxious Twins Citians in the midst of a violent crime spree, the Minnesota Sentencing Guidelines Commission apparently has quietly shelved its controversial proposal to reduce prison terms for some convicted felons. The whole ordeal moved a lot of concerned Minnesotans to learn more about the commission and the tone-deaf people who operate it

Forming the commission

The sentencing commission is one of 256 boards and commissions spread throughout Minnesota’s government, acting akin to a fourth governing branch. Almost no two are alike in who gets to appoint, who is eligible to serve, the pay rates (if any) offered, the service terms, and so on. But only one of them gets to determine how much time a convicted felon will spend in state prison.

That responsibility falls to the Minnesota Sentencing Guidelines Commission. The state legislature created the commission in the early 1980s to develop guidelines to help standardize felony sentencing.

The commission’s membership is formed through a combination of appointees who don’t reflect a bipartisan, non-political entity like many of the other state commissions. The chief justice of the Minnesota Supreme Court and the cabinet-level commissioner of corrections are ex officio members. In turn, the chief justice appoints two members: an appeals court judge and a district court judge. The governor then appoints seven additional members, which must include a county attorney (prosecutor), a police officer, a public defender, and a probation officer. The last three of the seven are considered “public” members, one of which must include a crime victim.

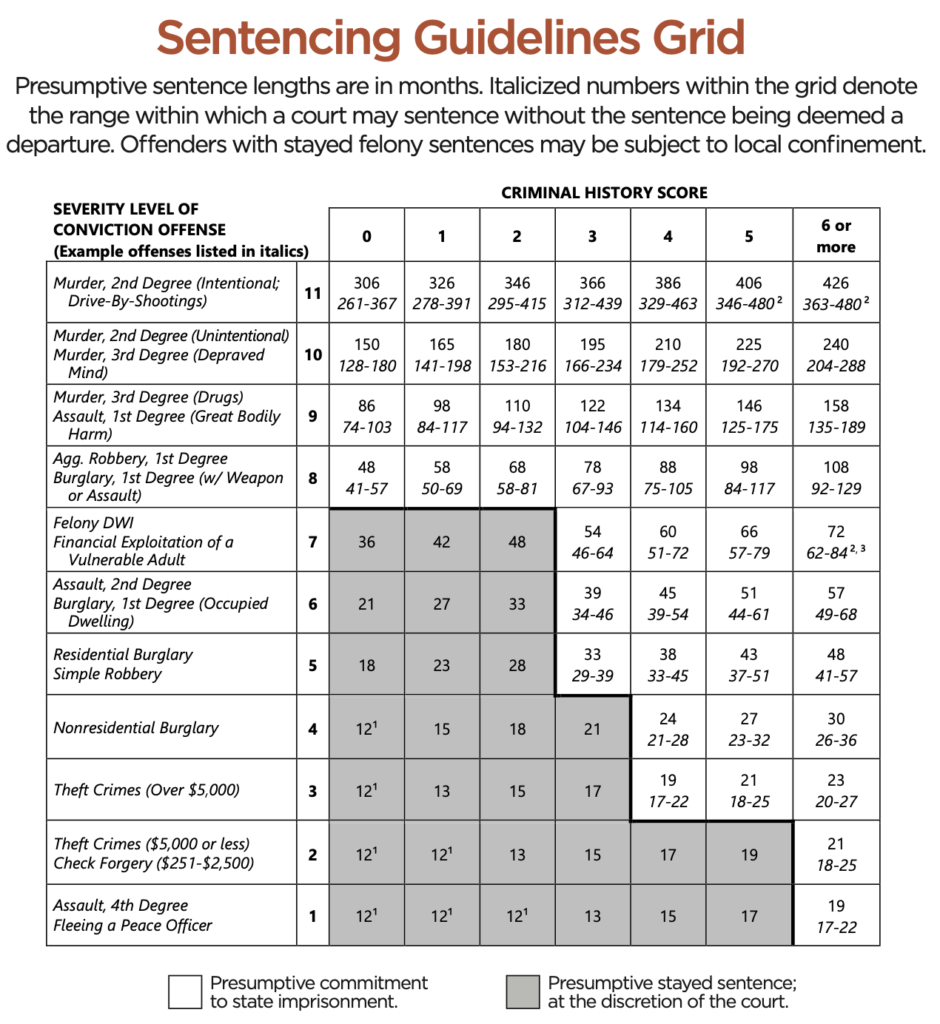

At present, eight of the 11 members were appointed by Gov. Tim Walz. Only one member self-identifies as a Republican. He is the district court judge appointed by the chief justice. The commission’s guidelines are based on a points system, with various factors adding points that result in longer sentences. Felons can accumulate up to six points for things such as previous felony convictions or whether the felon was currently on probation or parole.

The guidelines are portrayed on a grid, with the level of crime on the y-axis and the number of points (and resulting length of the sentence in months) on the x-axis. Judges are not required to follow the guidelines, and many don’t. Despite the grid’s recommendations, many convicted felons receive stayed sentences or probationary terms.

In 2020, judges adhered to the grid in 72 percent of their sentences; downward departures — sentences levied below the recommendation — totaled 26 percent. Upward departures were a mere 1.4 percent with the remaining cases classified as “unclear.”

Why reduce sentences?

The controversial proposal that prompted a firestorm of public opposition — including 3,800 letters of opposition coordinated by Center of the American Experiment — would have the effect of reducing sentencing for some offenders by dropping the “custody status” item from the points system. In other words, felons could not receive a longer sentence if they commit a new crime while on probation or parole.

Their rationale revolves around the progressive idea that incarceration does not deter crime and lengthy prison sentences do not reduce crime rates. One is reminded of the famous “Fox Butterfield effect,” first described by then Wall Street Journal columnist James Taranto. Fox Butterfield was a journalist for the New York Times, who in a 1997 piece expressed astonishment at FBI statistics showing falling crime rates despite increasing prison populations. Butterfield assumed that falling crime rates meant fewer people should be in prison. Taranto noted an alternative view that reverses the cause and effect. Lower crime rates were the result of more criminals in prison.

Some members of Minnesota’s current Sentencing Guidelines Commission go beyond the Butterfield effect. They apparently presume that incarcerating fewer criminals for shorter sentences will reduce crime rates, as the emphasis shifts from punishment to compassion and rehabilitation. The proposal brought before the commission would have codified this assumption. But Minnesotans currently experiencing some of the worst crime rates in the state’s history, disagreed.

How the sausage is made

One of the six votes in favor of the proposal was from a public member, Tonja Honsey, appointed by Gov. Walz. On her application for the position, she self-identified as a Native American, however, the New York Times reported in June 2020, Honsey had been accused of falsely representing her Native American heritage. The Times also reported that Honsey was the sole full-time employee of the Minnesota Freedom Fund, the organization that provides cash bail in order to release felons from pre-trial custody, including rioters from the George Floyd-related unrest. She is no longer listed on the Fund’s website as a staff member.

The Star Tribune reported back in 2019 that Honsey was believed to be the first appointee to the commission to be a formerly incarcerated female. Her past charges include drug-related offenses, check forgery, and theft. She describes herself as an “incarceration survivor.” Not surprisingly, she is a passionate advocate for shorter felon prison sentences.

On the current proposal, Honsey told the Pioneer Press “I think that we need to end this ‘us versus them’ when it comes to public safety,” adding “Public safety needs to include everyone.”

Also voting in favor of the proposal was Corrections Commissioner Paul Schnell. His perspective was reportedly strictly financial. Schnell oversees an annual budget of $660 million and the proposal was estimated to free up 538 prison beds once it takes effect and fewer convicted felons are sent to prison. But those newly emptied prison beds represent criminals now returned to the street.

Commission member David Knutson, a sitting District Court judge, opposed the proposal and told the Pioneer Press, “If a person is in custody or on probation, they are more culpable; they are more deserving; they are more blameworthy. We haven’t gotten their attention. They are out violating the safety of the public.”

An obvious viewpoint not represented in the debate or having a vote on the proposal was that of the victim. The designated public member crime victim seat was empty at the time and not filled until the January 2022 meeting. That member, Brooke Morath, was not appointed by the governor until November 2021. The seat on the commission designated for a police officer was vacant as of March. The proposal was not scheduled to be taken up at the March 10 meeting, so in all likelihood, this seat will remain vacant.

Misrepresentation

Schnell appeared to dismiss en masse the huge volume of public comments submitted both in writing and in person, as uninformed. He specifically decried what he called “tough on crime rhetoric,” and framed the issue as a “false choice” between being “tough on crime and soft on crime.” Without mentioning American Experiment by name, Schnell went out of his way to single out the “fearmongering rhetoric” of the “solicited, one-click emails.”

Commission member Michelle Larkin pushed back on Schnell’s characterization of the public comments. Larkin, a sitting judge on the state’s Court of Appeals, praised the public’s participation in the process and pointed out that 94 percent of public comments opposed the proposal.

She noted the large number of emails were from individuals containing personal comments.

Speaking as a former public defender, Judge Larkin observed that “it’s really hard to get sent to prison in Minnesota.” Larkin summarized much of the public sentiment on the issue, the concern over the justice system’s “revolving door,” and fear about rapid rises in violent crime, especially carjackings. She noted the disconnect between academic research supporting shorter prison sentences and the lived experience of the public.

It’s important to hold government agencies and representatives accountable for the policies they put in place. In the case of the Sentencing Guidelines Commission, they were preparing to enact new procedures without direct input from Minnesotans, which these policy decisions would have a direct affect. Minnesotans made their voices heard and got results, but has the state government learned its lesson?