Pensions: Keeping the Promise

Securing Retirement Benefits for Current and Future Public Employees

Updated November 20, 2014

To read this chapter as it appeared in the 2014 book, click here.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The Problem

Summary of the problem: Minnesota’s public employee pension system is broken. The state’s reported unfunded liabilities are estimated by the state to be $17.6 billion. If reasonable economic assumptions are used, the amount is far larger. This is a ticking fiscal time bomb for Minnesota. Escalating costs will force us to choose between reducing spending on core services that are essential to our quality of life, raising taxes by a far larger amount than the Legislature did in 2013, or breaking our promises to retirees. These choices can be avoided if we redesign the system now.

Summary of our solution: First, maintain and fully fund the defined benefit plan for retirees and current employees, honoring all earned benefits. Second, accurately state and fully disclose the true cost of pensions. Third, create a defined contribution plan for all new public employees that puts them on a path to a secure retirement without creating future unfunded liabilities. Fourth, take immediate steps to preserve and prudently grow pension assets while paying down the unfunded liability.

Summary of why this works: This solution keeps our promise to retirees and current employees while updating the retirement system to meet the needs of today’s public workforce. More importantly, it avoids a predictable fiscal crisis that will put school districts, and local and state government in the untenable position of choosing between funding past pension promises and delivering core services. It also takes backroom politics out of retirement savings and investments. These reforms would position Minnesota as a leader among states; we will be rewarded with more cost effective government and a stronger economy that will provide more good paying jobs.

Why you should care: Ignoring the problem puts everybody at risk—current and future retirees, taxpayers and consumers of public goods and services.

INTRODUCTION TO THE NATIONAL CONVERSATION ABOUT PUBLIC PENSIONS.

A recent Report of the State Budget Crisis Task Force detailed the fiscal problems that are plaguing most states—and public pensions are front and center.1 The task force reports state and local pension funds are “underfunded by approximately a trillion dollars according to their actuaries and by as much as $3 trillion or more if more conservative investment assumptions are used.” This underfunding poses a serious risk for future budgets. Independent experts across the political spectrum agree that pension funding is a problem that needs our immediate attention.2

What does this have to do with Minnesota? The vast majority of Minnesota’s public employees are in one of three defined benefit plans managed by the state: PERA (local employees including police and fire), TRA (K-12 school teachers) and MSRS (state employees). There are 311,885 active public employees counting on the state to manage their defined benefit retirement funds and 202,056 retirees, survivors and disabled people who are relying on a pension check. That means over 11 percent of Minnesota’s population (602,504 people) is counting on these plans for retirement security.3 Like many states, Minnesota has fallen behind in payments, putting pension promises and taxpayers at risk.

THE SIZE OF THE PENSION PROBLEM

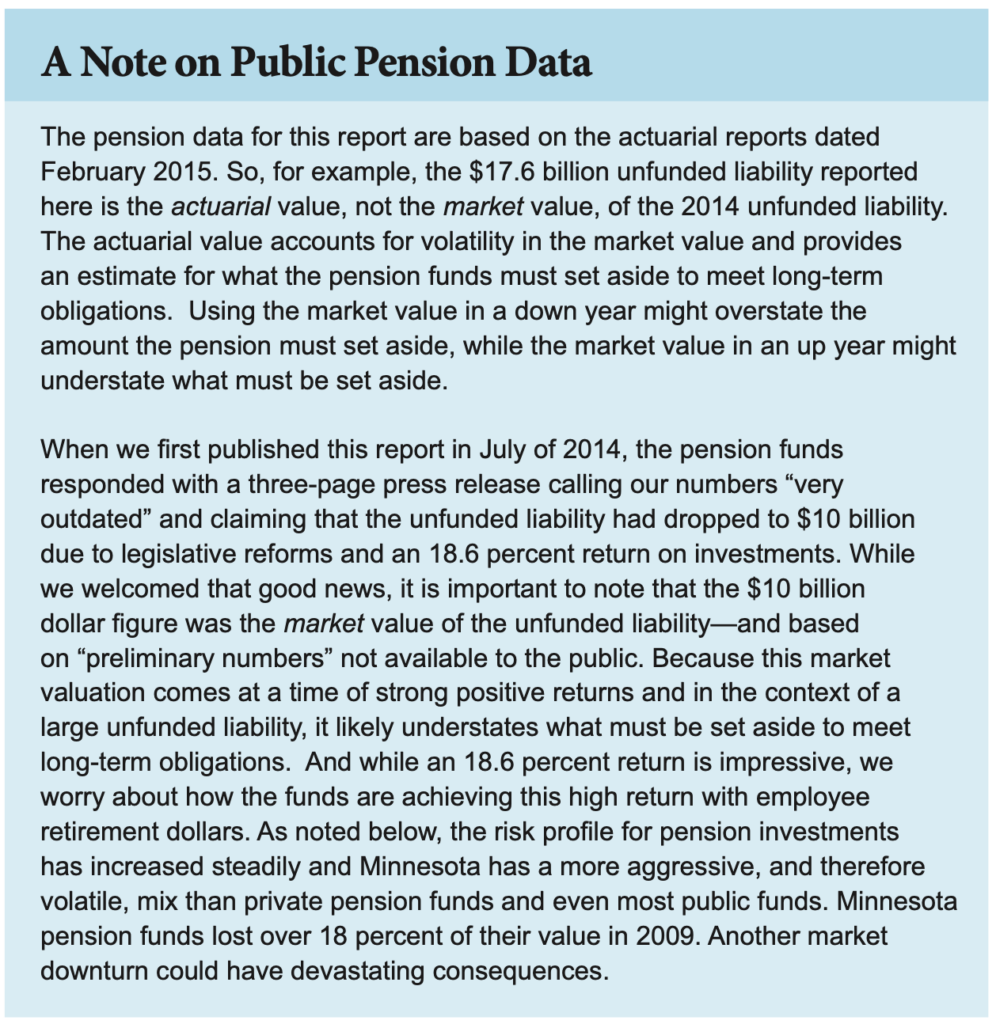

Minnesota’s public pension plans have a large and growing unfunded liability. The combined funds4 have dropped from 100% funding in 2001 to about 76 percent in 2014 (Figure 1). As of 2013, the state calculated the unfunded liability at $17.3 billion. The unfunded liability increased to $17.6 billion in 2014. These calculations were based on an assumed rate of return and a discount rate for liabilities that were excessive. As a result, the actual unfunded liability is probably larger.

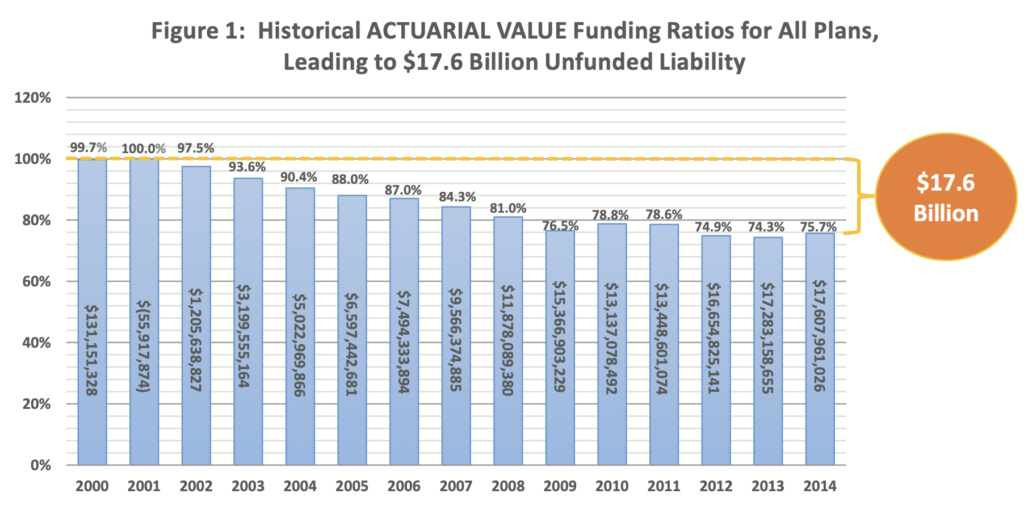

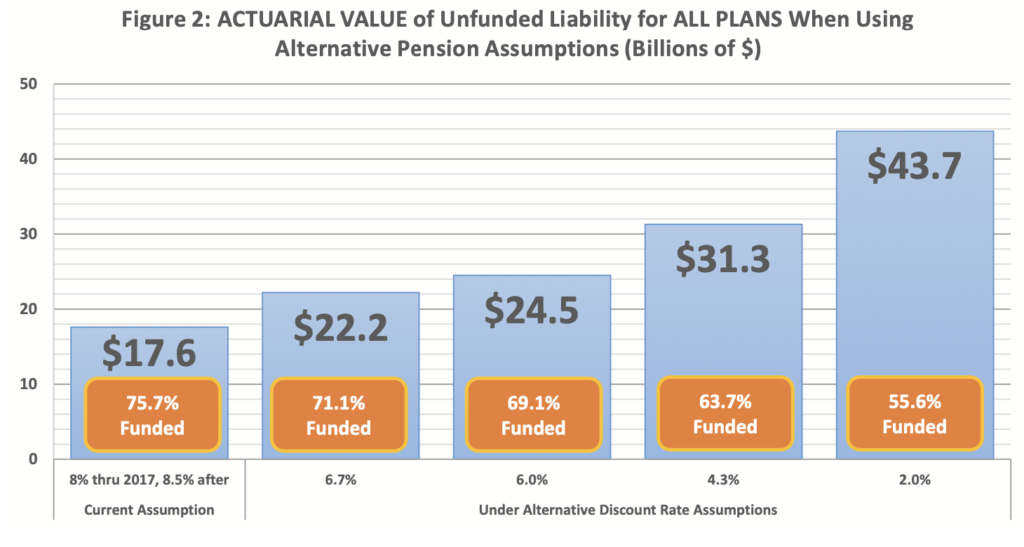

Minnesota State Economist Laura Kalambokidis outlined alternative assumptions for calculating the unfunded liability in testimony before the Legislative Commission on Pensions and Retirement (LCPR) in 2013.5 These alternative assumptions put the unfunded liability between $22.2 billion and $43.7 billion and drops the funding ratio from 74 percent to as low as 56 percent (Figure 2). A 2014 snapshot of the market value for the combined funds puts the unfunded liability between $11.5 billion and $28.5 billion (Figure 3).

* 2013 and 2014 does not include Volunteer Fire Plans and 2014 does not include Bloomington Fire because data was unavailable.

Source: Minnesota Legislative Commission on Pensions and Retirement, Minnesota Pension Plan Actuarial Reporting, Historical Data by Plan (February 18, 2015), available at http://www.commissions.leg.state.mn.us/lcpr/valuations.htm.

Sources: Calculations are based on the following formula: Present Value = Future Value / (1 + Discount Rate)^15. See Wake Forest University Law School, Law & Valuation, Chapter 1.3.2, at https://users.wfu.edu/palmitar/Law&Valuation/toc.htm. Alternative discount rate assumptions are drawn from a presentation by Laura Kalambokidis, Minnesota’s state economist. See Laura Kalambokidis, Rate of Return Assumptions for Minne- sota’s Public Pension Plans (August 29th, 2013), Aaa muncipal bonds/CBO Fair Market Value (6.7%); Aaa corporate bonds/Moody’s/FASB (6.0%); and 10-year treasury bond/riskless rate (4.3%), available at http://www.commissions.leg.state.mn.us/lcpr/documents/mtgmaterials/2013/Ka- lambokidis_LCPR_08292013_final.pdf. Note: 10-year treasury bond rates have dropped since 2013 to about 2 percent.

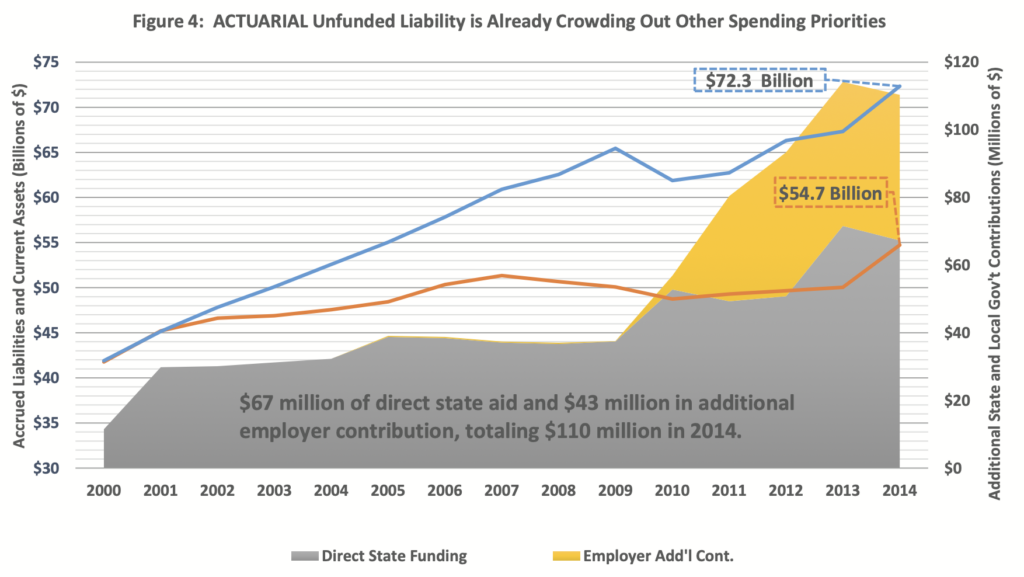

The unfunded liability is already burdening state and local budgets. While some underfunding (and overfunding) is expected in a defined benefit pension system, the amount and pace of growth of Minnesota’s unfunded liability is extreme and dangerous. It has already led to higher spending by state and local governments. Figure 4 shows how direct state aid and additional local government contributions grew in step with the growth of the unfunded liability.

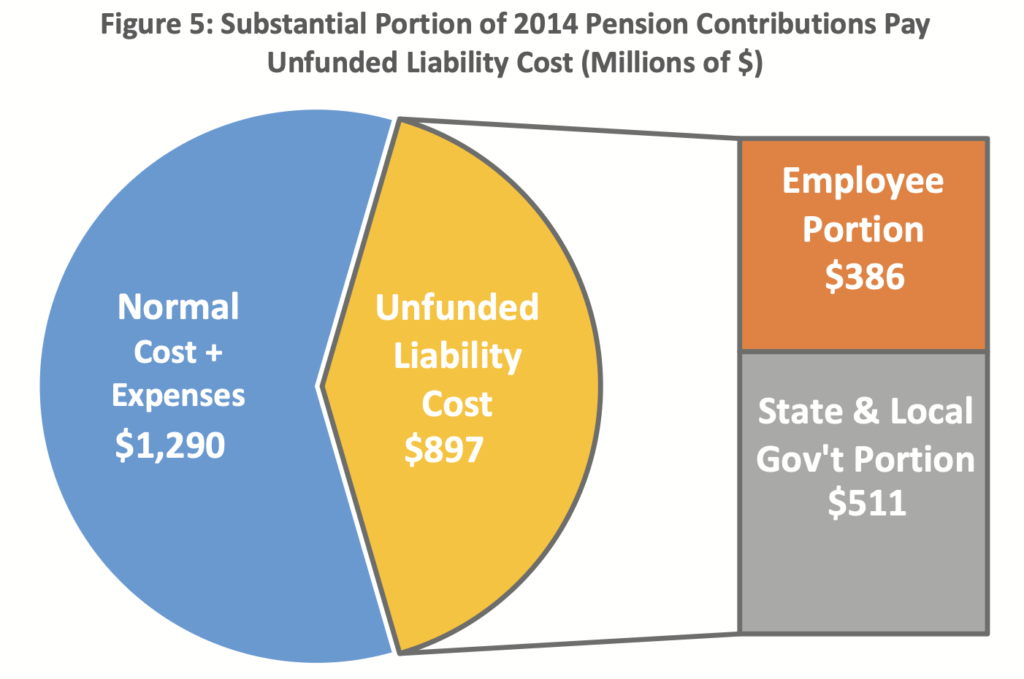

In 2014, additional employer contributions and cash aid from state and local government totaled $110 million. These additional payments are only a portion of the total price paid in 2014 to cover the unfunded liability. Actuarial valuation reports reveal Minnesota pension funds paid a total of $897 million in “supplementary contributions” to amortize the cost of the unfunded liability in 2014.6

These payments are funded by employee and employer payroll contributions, plus the additional payments ($110 million) shown in Figure 4. The $897 million total “supplementary contributions” is on top of the $1.290 billion paid to fund the current, or “normal cost” plus administrative expenses of the pensions. (The “normal cost” is the cost of projected future benefits allocated to the current plan year.)

Source: Minnesota Legislative Commission on Pensions and Retirement, Minnesota Pension Plan Actuarial Reporting, Historical Data by Plan (February 18, 2015). Direct state funding excludes Volunteer Fire Plans funded through insurance premium taxes.

Assuming employees and employers pay proportional shares based on their annual contributions, then the $897 million in unfunded liability payments was split between employees ($386 million) and state and local governments ($511 million) as shown in Figure 5.

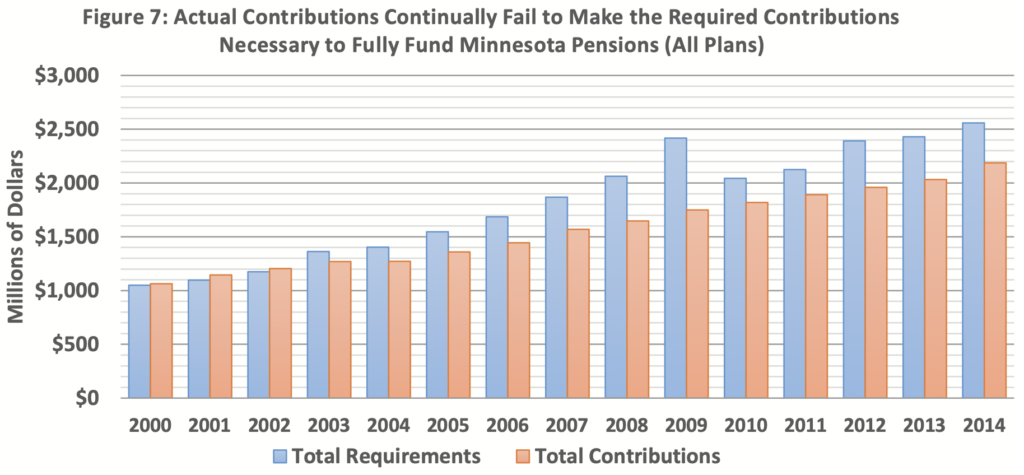

The $897 million in supplemental contributions paid in 2014, however, fell far short of the $1.247 billion supplemental contribution needed to cover the actuarial required contribution (ARC)—the contribution that should be made to both cover the normal costs and pay down the unfunded liability.7 The annual payment Minnesota needs to make to actually pay down the unfunded liability was, therefore, over 100 percent of the normal cost of the pension plans.

Each day, Minnesota’s defined benefit plans take on new unfunded liabilities but fail to make the full required contributions. In 2014, this deficiency totaled $350 million.8 At the same time, the state is paying earned benefits to retirees (plus a COLA to protect against inflation).

In other words, the state is in a hole and it just keeps digging. The 2014 Valuation Report for MSRS (Minnesota State Retirement System), which has one of the better funding ratios, puts the problem in stark terms. The report said that under current assumptions,

“an infinite number of years would be required to eliminate the unfunded liability (the unfunded liability will never be eliminated)… the unfunded liability as a percent of pay will increase without limit to an infinite amount.” 9

Source: Minnesota Legislative Commission on Pensions and Retirement, 2014 Valuation Reports, available at http://www. commissions.leg.state.mn.us/lcpr/valuations.htm. Calculations include all open pension plans with 2014 data available, which excludes Elective State Officers Retirement Plan and Legislators Retirement Plan.

THE CROWDING OUT EFFECT.

Extra pension costs are already “crowding out” other spending priorities.

As noted above, the total state and local government portion of the $897 million “supplemental contribution” toward the unfunded liability was $511 million in 2014. (Figure 5). Of that, $110 million comes from additional state aid ($67 million) and local aid ($43 million).10 These backward looking “extra” payments toward the unfunded liability are crowding out funding for other priorities like tax relief or other spending priorities. What else does that buy?

- State taxpayers and City of Minneapolis taxpayers are going to pay a combined $498 million for the Viking Stadium—less than the $511 million dollar unfunded liability payment made by state and local governments for just one year.11

- $67 million in state aid is enough to fund the state’s pre-K school readiness program for two years, or

- Minnesota’s business and workforce development programs for a year.12

Source: Minnesota Legislative Commission on Pensions and Retirement, Minnesota Pension Plan Actuarial Reporting, Historical Data by Plan (February 18, 2015s).

The two largest shares of the $897 million unfunded liability payment went to TRA ($154 million) and PERA-General ($179 million). Again, what else does that buy?

- $154 million could pay salaries for an additional 2,400 teachers.13

- $179 million could double the 2014 renters property tax refund, buy 732 snowplows, add 18 miles of new lanes to an existing highway,14 or maintain 12,000 miles of local roads.15

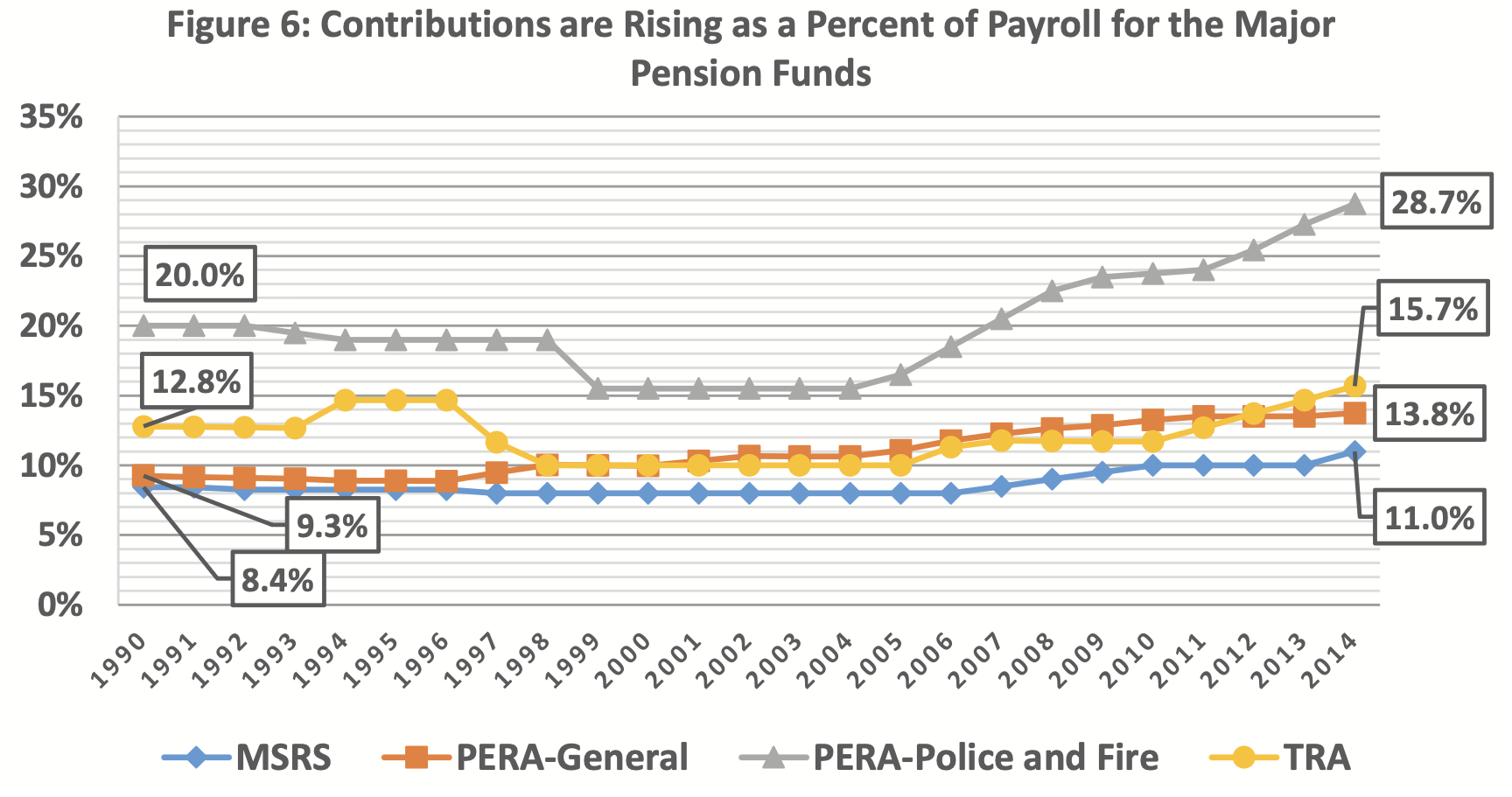

We are paying more but getting less. Figure 6 shows that contributions as a percent of payroll decreased in the 1990’s (perhaps sowing the seeds for today’s underfunding) and then increased steadily in the 2000s. Employees, state government, school districts and local governments are all being hit by higher contributions to the existing system, yet the problem continues to grow.

And even with increased payments, the state has not created a fully funded, secure retirement system.

HOW DID MINNESOTA GET INTO THIS MESS?

Skipping full payments. Public employers and employees are not making the necessary annual required contributions to keep the pension system actuarially sound. Minnesota started shorting payments in the early 2000’s (Figure 7). This means public employers are pushing off some of today’s costs onto future employees and taxpayers and significantly raising the total costs of pension obligations.16

Source: Minnesota Legislative Commission on Pensions and Retirement, Minnesota Pension Plan Actuarial Reporting, Historical Data by Plan (January 16, 2014), available at http://www.commissions.leg.state.mn.us/lcpr/valuations.htm.

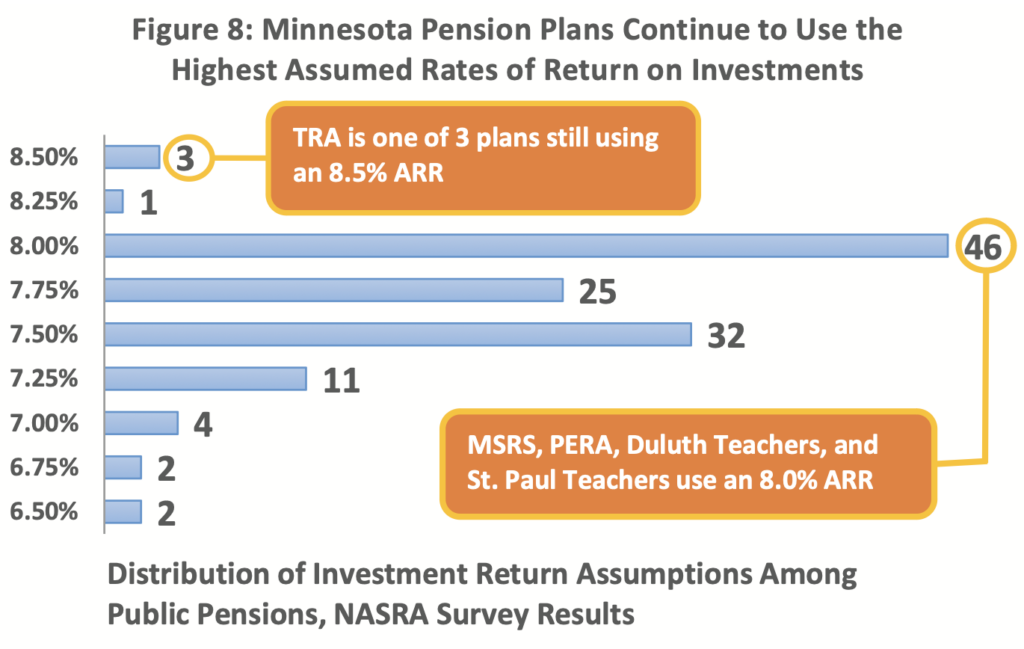

Unrealistic assumptions. The state is underestimating what it actually costs to fund the promised benefits.17 For example, most U.S. public pension funds—not just Minnesota’s—use unrealistic assumptions about what they will earn on assets. But Minnesota is an outlier even among U.S. public pension funds. Since 1989, the state has used the highest assumed rate of return (ARR) in the nation (8.5 percent). This optimistic assumption was revised to 8.0 percent, effective June 30, 2015. Minnesota has been reluctant to permanently lower the ARR to a more realistic number because this will further increase contribution rates (Figure 6).18

All the funds except TRA (Teachers Retirement Association) requested the new ARR of 8.0 percent. TRA is expected to follow suit in 2016. Minnesota continues to lag behind national trends for an ARR of less than 8.0 percent (Figure 8). Further compounding the problem, Minnesota uses this high rate of return to discount future liabilities. Because pension benefits are a binding legal obligation, state and local governments have to pay them even if investment earnings fall short.19 This is why the cost of future benefits (liabilities) should be calculated using a discount rate that reflects this lower risk, rather than assumed investment returns. This is the approach taken by private sector pension plans and public plans in Canada and Europe.20 A lower discount rate would require that more, not less money is set aside to cover guaranteed benefits. As noted above, if you calculate Minnesota’s unfunded liability using the more realistic discount rates suggested by Minnesota’s state economist, the unfunded liability ranges from $22.2 billion to $43.7 billion or 56 cents for every dollar promised to retirees (Figure 2).

Source: National Association of State Retirement Administrators, Public Pension Plan Investment Return Assumptions (May 2015). Note: Due to financial distress and poor demographics, the Duluth teachers fund merged into TRA July 1, 2015.

Opaque, hard to understand techniques. Minnesota uses a variety of management techniques (e.g. long amortization periods, level percent of pay rather than level dollar payments toward the unfunded liability) to postpone dealing with the problem. These opaque techniques, which are hard to understand, delay the pain of paying for promised benefits. But as the Rockefeller Institute recently warned, “The future does arrive.”21

Not so benign neglect and backroom political mischief. Politicians are not good managers of other people’s pensions. And defined benefit plans require a lot of managing. In theory, a defined benefit plan is the most cost-effective vehicle for public pensions. In practice, it has not turned out well. No matter how dedicated and honorable, politicians operate on two-year budget and election cycles. The temptation to ignore pension funding problems is great. State lawmakers are very busy and pensions are very complex; most lawmakers do not understand pensions and rely on their pension commission colleagues to determine policy.22 The pension commission members in turn are greatly influenced by and dependent on public union lawyers/ lobbyists, pension administrators, pension staff and representatives of the defined benefit industry.23 Each pension plan also has a board of trustees. A quick glance, for example, at the trustees of TRA (Teachers Retirement Association) demonstrates the intimate relationship between TRA and Education Minnesota, the teachers union.24

MINNESOTA’S LEGISLATURE HAS TRIED TO FIX THE PENSION PROBLEM.

The legislature has attempted to manage the pension problem. For example, in 2007 it corrected an egregious practice it had previously enacted that was draining pension assets and creating major inequities among retirees. Specifically, they eliminated increases to base pensions for retirees paid when the State Board of Investment (SBI) made more than the targeted 8.5 percent on investments.25

Following the 2008 financial crisis, the state passed politically difficult “sustainability measures.” The 2010 omnibus legislation attempted to put the pension plans on a sound footing. The pain was spread around to taxpayers and employees (higher contributions) and retirees (COLAs reduced until the plans return to 90 percent market funding).26 These legislative efforts may have prevented the kind of financial meltdown we see in states like Illinois or cities like San Bernardino, California. If full and current funding was the objective, however, the 2010 measure has fallen seriously short. The reason is that the 2010 legislation did nothing to address the fundamental problems in the defined benefit system.

Since then, additional refinements have been signed into law, yet the gap between the assets and liabilities continues to grow.27 The 2013 pension bill included a “contribution stabilization” measure that automatically lowered or raised contributions in response to funding levels. In the 2015 omnibus bill, the stabilizer changed from mandatory to voluntary. The omnibus also revised the on and off triggers for COLA payments to protect pension assets. It remains to be seen how these changes will impact funding levels.28

Market Crash Did Not Cause Unfunded Liability. Though the market crash following the 2008 financial crisis did contribute to the unfunded liability problem, it gets way too much blame. It is a convenient narrative for pension administrators and politicians trying to explain dropping funding ratios. The truth is the state was already propping up certain funds in 2000 when the assets and liabilities (all funds) began to move apart at a steady pace (Figure 4).29 The pension funds dropped from 100 percent to 81 percent funded in 2008 after 6 years of failing to pay the full ARC. Then in 2009, the pension funds lost 18.8% of their asset value, dropping the funding ratio to 76.5 percent (Figures 1 and 7).

Solid long term returns have not closed the gap. Despite significant volatility, the State Board of Investment has earned annualized returns of 8.4 percent over the last 10 years and 10 percent since 1980. SBI reported a return of 18.6% in 2014. But these returns have not been enough to improve the funding ratio, let alone cover the unfunded liabilities. These market returns cannot make up missed ARC payments, underestimated benefit costs and inevitable market losses. Guaranteed benefits must be paid regardless.30

An unfunded pension system is entirely predictable. The 2008 financial crisis did accelerate the impact of fundamental management errors and political mischief. The complexity of managing a defined benefit system (long term horizons that require a solid grasp of actuarial science) and the mischief of backroom politics (short term horizons that require a solid grasp of political science) destine defined benefit plans to regular and severe underfunding.31

CONSEQUENCES IF THE PENSION PROBLEM IS NOT FIXED.

- “Crowding Out” effect. Operating budgets will be increasingly constrained by requirements to pay for past pension promises rather than current services or future infrastructure.

- Increased borrowing costs and scrutiny. The rating agency Moody’s recently recalculated pension debt using a corporate bond discount rate. As a result, Moody’s lowered the bond rating of municipalities and states to better reflect their ability to pay unfunded pension liabilities. A lower rating results in higher borrowing costs, which in turn squeezes the public purse with absolutely no added value. Dozens of Minnesota cities have already been downgraded.32

- Putting pension assets at risk. The legislature directs the SBI to aim for

an 8.0 to 8.5 percent rate of return on pension assets. By contrast, the S&P 500 10-year annualized return through 2014 was about 7.6 percent (the highest 10-year annualized return since 2006).33 SBI’s investment returns are supposed to supply a good chunk of pension benefits ($.69-$.73 out of every dollar);34 this keeps the contribution rates down. The optimistic assumed rate of return (ARR), missed ARC payments and recent investment losses place enormous pressure on SBI to not just meet but to exceed the target. It is no surprise then that the risk profile for investments has increased steadily over time. Minnesota’s asset mix is more aggressive than private pension funds and even most public funds.35 Another market downturn could have devastating consequences for the pension funds.36 - The pension problem will hurt job creation both in the public and private sector. The public sector will face constraints in hiring as it devotes an increasing share of revenue to pension costs. This means fewer teachers in the classroom and police officers on the street. It also puts upward pressure on taxes without delivering any extra value. This will discourage investment and hurt job creation in the private sector.

DESIGNING A SOLUTION THAT IS TRANSPARENT, PREDICTABLE, AFFORDABLE AND FULLY FUNDED

The solution must address all stakeholders: retirees, current and future employees, taxpayers and state and local governments. And the solution should be transparent (understandable to employees, taxpayers and legislators). The costs should be predictable, affordable and fully funded as benefits are earned.

Summary of the Solution. We should honor our promises to retirees and current employees. In the near future, however, we should move from a partially funded defined benefit system to a fully funded defined contribution system that takes control of retirement decisions away from politicians and bureaucrats and gives control to public employees.

Recommendation 1: Maintain and fully fund the defined benefit plans for retirees and current employees, honoring all earned benefits.

Pensions are an important ethical and legal obligation that must be honored. That means fully funding, on a current basis, retirement benefits as they are earned.37 This keeps the promise to public employees but also stops the practice of shifting the cost to future employees and taxpayers. It also means realistically addressing today’s unfunded liability. To be clear, this is not a recommendation to increase taxes. It is a recommendation to fully fund pensions from existing revenue, which may require spending cuts elsewhere.

Recommendation 2: Accurately state and fully disclose the true cost of pensions for reporting purposes.

Reporting policy is distinct from funding policy. Accurate reporting will start a much needed state-wide conversation that will better inform the debate and lead to the best benefit and funding policies.

- Use realistic assumptions. Use a more realistic assumed rate of return (affects contribution rates and investment policies) and a more defensible discount rate to value liabilities (future benefits).38 Lowering the ARR to 8.0 percent is a good start but still postitions Minnesota as an outlier even among public funds. New accounting standards from GASB are in effect as of 2014, so we should start to see the impact on funding policy (as distinct from reporting) in the next few years.

- Make public pension data transparent and accessible. Pension funding data should be published in an accessible format and place by MMB (Minnesota Management and Budget) and on municipal websites. Require the state auditor and legislative auditor to report annually on unfunded liabilities for pensions.39

- Encourage new talent and oversight for pension administration. Revise laws that require the state to hire executives from a limited pool of retirement system administrators. We should explicitly allow private sector talent to be tapped.40 We should review the makeup of pension boards and add taxpayer and young employee representatives to balance the influence of union representatives and retirees.

- No more cash bailouts. Stop cash bailouts from state taxpayers.41 If a fund is in distress, that fund should make adjustments (e.g. raise contributions, lower benefits) to close the gap.42 Taxpayers already pay the employer contribution and they are on the hook for the unfunded liability. They should not cover the employee contribution, as well. After all, they do not get the pension benefit and need to save for their own retirement.

Recommendation 3: Create a defined contribution plan for all new public employees that puts them on a path to a secure retirement and give current employees the option to join.

- To stop adding new liabilities to the current system, the defined contribution plan needs to be required for all new employees. There should also be an option for employees in the current defined benefit plan to move to the defined contribution plan.43

- A flexible defined contribution plan should offer employees a wide range of options. Some employees will want full control and responsibility over their investments while others will prefer to leave the management of investments to others (much like the current defined benefit plan). Similarly, some employees will want an account they draw on as needed (like 401a/403b) while others will want a fixed income (annuities). Employees should have the flexibility to change their plans to reflect their individual needs.44

- The Legislative Auditor should hire an outside consultant to prepare a report for the governor and Legislature on how to implement a defined contribution system. The consultant should not be hired by the pension plans or the Legislative Commission on Pensions and Retirement because of the inherent conflict of interest (closing the plans that they administer to new members).45

Note: Minnesota already offers defined contribution plans. Many Minnesota State Colleges and Universities (MNSCU) employees already take advantage of defined contribution options through an asset manager called TIAA CREF.46 This successful plan could serve as a model for Minnesota’s new defined contribution plan. In theory, the State Board of Investment could manage a defined contribution plan—or the state could choose outside asset managers. These plans are popular because the assets are portable: employees can choose without penalty to change employers and when to retire. And unlike a defined benefit, they feature assets that can be inherited by an employee’s spouse, children or other heirs.47

Recommendation 4: The state should take immediate steps to preserve and prudently grow pension assets while paying down the unfunded liability.

- Assets should be preserved. The funding ratio for payment of COLAs to retirees should be increased from 90% to 100% over a period of years.48 COLAs should be further reduced on base pensions that received gratuitous investment-based post-retirement increases; this will address the drain on assets created by this unique class of benefits and the large inequities among retirees and employees whose contributions help to cover these benefits.49

- Don’t chase unrealistic returns. The SBI asset allocation and investment policies should be reviewed for risk with an eye toward lowering the assumed rate of return to a more reasonable target. The time when returns fall short is usually the worst time to increase contributions.

- Fix the debt payment. The current unfunded liability amortization schedule should be changed to a fixed payment (“level dollar” instead of the current “level percent of pay”). This will pay off the debt sooner and maximize savings.50

- Limit borrowing to pay for benefits. Municipalities are allowed to issue bonds to pay retirement benefits (pensions or OPEB) without a referendum. Review the statutes that allow this borrowing. At a minimum, require a referendum.51

The pension problem is one of the most difficult fiscal and political challenges facing the State of Minnesota. Moving new employees into a defined contribution system is achievable in the near future. The more difficult task will be paying down the unfunded liabilities for the existing defined benefit plans. Finding the money from existing revenue will take uncommon courage and talent from our state leaders. But it must be done. We must keep our promises.

Kim Crockett is Center of the American Experiment’s Chief Operating Officer, Executive Vice President, and General Counsel. She is also Chair of the Federalist Society’s Minnesota Lawyers Chapter. Kim had a long legal career in commercial real estate law before joining the Center. She has a B.A. in Philosophy from the University of Minnesota and a J.D. from Penn Law.

ENDNOTES

1 Richard Ravitch and Paul Volker (Co-Chairs), Report of the State Budget Crisis Task Force (July 2012): p. 12, available at http://www.statebudgetcrisis.org/wpcms/wp-content/ images/Report-of-the-State-Budget-Crisis-Task-Force-Summary.pdf. See also, Donald

J. Boyd and Peter J. Kiernan, Strengthening the Security of Public Sector Defined Benefit Plans (The Rockefeller Institute, January 2014), available at http://www.rockinst.org/pdf/ government_finance/2014-01-Blinken_Report_One.pdf; and Patten Priestley Mahler, Matthew M. Chingos, and Grover J. “Russ” Whitehurst, Improving Public Pensions: Balancing the Competing Priorities, Brown Center on Education Policy (Brookings Institute, February 2014), available at http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/research/ files/papers/2014/02/26%20public%20pension%20reform/improving%20public%20 pensions_final.pdf; Andrew Biggs, The Multiplying Risks of Public Employee Pensions to State and Local Government Budgets (American Enterprise Institute, December 2013), available at http://www.aei.org/files/2013/12/18/-the-multiplying-risks-of-publicemployee-pensions-to-state-and-local-government-budgets_142010313690.pdf; and Andrew Biggs, “When it Comes to Public Pensions, There’s Funding and Then There’s ‘Funding’,” American Enterprise Institute, January 15, 2014, available at http://www.aei. org/article/economics/when-it-comes-to-public-pensions-theres-funding-and-then-theres-funding/.

2 Donald J. Boyd and Peter J. Kiernan, Strengthening the Security of Public Sector Defined Benefit Plans (The Rockefeller Institute, January 2014), available at http:// www.rockinst.org/pdf/government_finance/2014-01-Blinken_Report_One.pdf; Patten Priestley Mahler, Matthew M. Chingos, and Grover J. “Russ” Whitehurst, Improving Public Pensions: Balancing the Competing Priorities, Brown Center on Education Policy (Brookings Institute, February 2014), available at http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/ research/files/papers/2014/02/26%20public%20pension%20reform/improving%20 public%20pensions_final.pdf; and Patrick McGuinn, Pension Politics: Public Employee Retirement System Reform in Four States (Brookings Institute, February 2014), available at http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/research/files/papers/2014/02/26%20public%20 pension%20reform/pension%20politics_final_225.pdf.

3 Another 162,496 people paid into the pension system at one time or another but did not “vest.” Minnesota Legislative Commission on Pensions and Retirement, 2014 Actuarial Valuation Results, Summary of All Plans (February 18, 2015): p. 2, available at http://www.commissions.leg.state.mn.us/lcpr/documents/valuations/2014/2014_ valuation_summary_ava_2-yr.pdf; and U.S. Census data for Minnesota.

4 For simplicity, we combine all funds (MSRS, PERA, TRA and others included under “All Plans” by the LCPR Valuation Report) and treat them as a whole (“combined funds”). We note that each fund has its own assumptions, funding ratio and other distinct features.

5 Laura Kalambokidis, Rate of Return Assumptions for Minnesota’s Public Pension Plans [PowerPoint slides], Minnesota Legislative Commission on Pensions and Retirement Meeting, August 29, 2013, available at http://www.commissions.leg.state. mn.us/lcpr/documents/mtgmaterials/2013/Kalambokidis_LCPR_08292013_final.pdf

(suggested yields to consider were the 2013 10-year treasury/riskless rate of 4.3%, Aaa corporate bonds/Moody’s and FASB rate of 6.0%, Aaa municipal bond/CBO Fair Value approach rate of 6.7%). We updated Figure 2 using the 2015 10 year treasury rate of 2 percent.

6 Plans in this calculation are all open funds with 2013 data available and include MSRS, MSRS-Correctional, State Patrol, Judges Retirement Plan, PERA-General, PERA-Correctional, PERA-Police and Fire, MERF, TRA, DTRFA, & SPTRFA.

7 The full actuarially required contribution for these pension funds was $2.6 billion. Minnesota Legislative Commission on Pensions and Retirement, 2014 Actuarial Valuation Results, Summary of All Plans (February18, 2012): p. 2, available at http:// www.commissions.leg.state.mn.us/lcpr/documents/valuations/2014/2014_valuation_ summary_ava_2-yr.pdf.

8 The actuarially required contribution (ARC), missed by $350 million for “All Funds” is what full funding looks like under current assumptions. Minnesota Legislative Commission on Pensions and Retirement, 2013 Actuarial Valuation Results, Summary of All Plans (February 18, 2014): p. 2, available at http://www.commissions.leg.state.mn.us/ lcpr/documents/valuations/2014/2014_valuation_summary_ava_2-yr.pdf.

9 Gabriel Roeder Smith & Company, Minnesota State Retirement System State Employees Retirement Fund: Actuarial Valuation Report as of July 1, 2013 (November 26, 2013): p. 1, available at http://www.commissions.leg.state.mn.us/lcpr/documents/ valuations/2013/2013valuation.msrs.general.pdf.

10 $67 million comes from state aid and $43 million from local governments. Minnesota Legislative Commission on Pensions and Retirement, 2013 Actuarial Valuation Results, Summary of All Plans (January 22, 2014), available at http://www. commissions.leg.state.mn.us/lcpr/documents/valuations/2013/2013_valuation_ summary_ava_2-yr.pdf.

11 “New Stadium Q&A,” Minnesota Vikings Football, accessed August 10, 2015, http://www.vikings.com/stadium/new-stadium/faq.html#nvs-construction.

12 Minnesota Management and Budget, Consolidated Funds Statement (June 27, 2014), available at http://mn.gov/mmb/images/CFS_May2014.pdf.

13 The average teacher salary in Minnesota is $54,945. Minnesota Department of Education, Minnesota Report Card, 2013 Staffing Profile, at http://rc.education.state. mn.us/.

14 “Transportation FAQs,” American Road &Transportation Builders Association, accessed November 7, 2014, http://www.artba.org/about/transportation-faqs/#20; or Rails to Trails, What is the Cost of Constructing a Mile of Highway? (n.d.), available at http://www.railstotrails.org/resources/documents/whatwedo/policy/07-29-2008%20 Generic%20Response%20to%20Cost%20per%20Lane%20Mile%20for%20widening%20 and%20new%20construction.pdf.

15 Itasca County estimates it costs $15,500 per mile per year to maintain a bituminous road. Karen Grandia, 5-Year Plan for Highway Improvement Projects (Itasca County, April 8, 2014), available at https://www.co.itasca.mn.us/Home/Departments/Transportation/ Documents/5%20year%20plan.pdf; and Bill Salisbury, “Road to Minnesota transportation funds is not a smooth one” Pioneer Press, July 6, 2013, available at http://www.twincities.com/ci_23607277/road-minnesota-transportation-funds-is-not-smooth-one.

16 See pension debt schedules Figures 1 and 2 in Josh McGee, The Transition Cost Mirage: False Arguments Distract from Real Pension Reform Debates (Arnold Foundation, March 2013), available at http://www.arnoldfoundation.org/sites/default/files/pdf/LJAF_Transition_Cost_Policy_Brief.pdf. The unfunded liabilities are assets that are not available to SBI for investing (so the funds miss out on their earning power). In a very real sense, the state has “borrowed” from the pension assets at a high rate (the real rate of return or in theory the ARR of 8.5 percent).

17 Minnesota also uses long amortization periods (25-30 years) to pay off unfunded liabilities, which pushes costs on to future employees and generations of taxpayers. GASB now recommends that the amortization period not extend beyond the average expected service years of active and inactive members (more like 15-17 years). For a discussion on GASB Rules 67 and 68, see News Release, Governmental Accounting and Standards Board, “GASB Improves Pension Accounting and Financial Reporting Standards,” June 25, 2012, available at http://www.gasb.org/cs/ContentServer?pagename=GASB/GASBContent_C/GASBNewsPage&cid=1176160126951. The rules are explained in Bill Karbon, “GASB’s New Rules on Uniformity and Disclosure,” Plan Consultant (Winter 2014).

18 In 2012, the state dropped the rate to 8.0 percent for one year, adding a point (0.1%) each year until it reaches 8.5 percent again after five years. For insights into the political compromise that gave us this “select and ultimate” rate, see Hazel Bradford, “Public DB plans follow corporate lead in using ‘select and ultimate’ rates,” Pensions & Investments, August 8, 2012, available at http://www.pionline.com/article/20120808/ ONLINE/120809942/public-db-plans-follow-corporate-lead-in-using-select-and-ultimate-rates. While the “select and ultimate” approach is new, it is supposed to feature a longer time frame so that the change has an actuarial impact on the system. From an actuarial standpoint, which takes the long view, five years is not long enough to have any notable impact. It is not clear if Minnesota’s reduced ARR improved the calculation of future liabilities or reduced any investment risks (all benefits of a lower ARR if used over a long time frame).

19 The COLA, however, can be reduced for current retirees. See Swanson v. State, No. 62-CV-10-05285 (Minn. Dist. Ct., June 29, 2011). For a discussion on Minnesota case law, see Amy Monahan, Understanding the Legal Limits on Public Pension Reform (American Enterprise Institute, May 2103): p. 6, available at http://www.aei.org/ wp-content/uploads/2013/05/-understanding-the-legal-limits-on-public-pension-reform_104816268458.pdf.

20 See Donald J. Boyd and Peter J. Kiernan, Strengthening the Security of Public Sector Defined Benefit Plans (The Rockefeller Institute, January 2014): pg. viii, available at http://www.rockinst.org/pdf/government_finance/2014-01-Blinken_Report_One.pdf (discussing the U.S. public pension system versus private funds and other countries). For a discussion on how to value pension liabilities, see Paul Angelo, Understanding the Valuation of Public Pension Liabilities: Expected Cost Versus Market Price (American Enterprise Institute, May 2013), available at http://www.aei.org/papers/economics/ retirement/pensions/understanding-the-valuation-of-public-pension-liabilities-expected-cost-versus-market-price/.

21 Donald J. Boyd and Peter J. Kiernan, Strengthening the Security of Public Sector Defined Benefit Plans (The Rockefeller Institute, January 2014): p.viii, available at http:// www.rockinst.org/pdf/government_finance/2014-01-Blinken_Report_One.pdf.

22 For a good primer for legislators and citizens, see Minnesota Center for Fiscal Excellence, Fixing Minnesota’s Public Pensions: What Every Citizen Should Know (April 2014), available at http://www.fiscalexcellence.org/our-studies/pension-guide-2014-final. pdf.

23 The National Institute on Retirement Security (NIRS) is a champion for public defined benefit systems and regularly testifies at the pension commission. The board of directors is dominated by public retirement systems. For more detail, see Robert Costrell, “GASB Won’t Let Me” – A False Objection to Public Pension Reform (Arnold Foundation, May 2012): p. 13, fn. 16, available at http://arnoldfoundation.org/img/LJAF-Policy-Perspective-GASB-Wont-Let-Me.pdf.

24 See “Board of Trustees,” Minnesota Teachers Retirement Association, accessed November 7, 2014, https://www.minnesotatra.org/administration/bdtrustees.html.

25 See Minnesota Office of the Legislative Auditor, Postemployment Benefits for Public Employees (January 2007), available at http://www.auditor.leg.state.mn.us/ped/pedrep/ postemployment.pdf.

26 Some members of the Legislature, rather than focusing on how to pay off the unfunded liability, have asked the state actuaries how to get to 90% funding so they can increase the COLA for retirees again. The dilemma: once you start paying an increased COLA, the funding ratio drops below 90% again. See William V. Hogan & Timothy J. Herman, July 1, 2013 Actuarial Review of the Retirement Systems under the Minnesota Legislative Commission on Pensions and Retirement (Milliman, January 31, 2014): p. 7, available at http://www.commissions.leg.state.mn.us/lcpr/documents/ valuations/2013/2013_actuarial_review_milliman.pdf.

27 Pension Omnibus bills are summarized by the Legislative Commission on Pensions and Retirement and available at http://www.commissions.leg.state.mn.us/lcpr/ sessionsummaries.htm.

28 See summary of Article 3, 2014 Omnibus Pension Bill, Edward Burek to Members of the Legislative Commission on Pensions and Retirement, “2014 Omnibus Retirement Bill (H.F. 1951, 4th Engr.), as Sent to the Governor,” May 20, 2014, available at http:// www.commissions.leg.state.mn.us/lcpr/documents/omnibus/2014/H1951-4_Summary_ of_4th_Engr.pdf . This change may be in response to new GASB Rules 67 and 68 (contribution policies are expected to change to avoid asset depletion and due to pressure from new rules on the discount rate). See Bill Karbon, “GASB’s New Rules on Uniformity and Disclosure,” Plan Consultant (Winter 2014).

29 There are three major pension systems (PERA, TRA and MSRS), plus several independent funds, all with individual funding ratios and valuations. For purposes of simplicity, we are combining them here.

30 See Center for Public Finance Research, Public Pensions in Minnesota: Re-Definable Benefits and Under-Reported Performance (May 2006): p 46, 50-51, available at https:// www.fiscalexcellence.org/our-studies/public-pensions-in-minnesota-final.pdf.

31 The pension plans, individually and as a group, suffer from other unsound practices that reduce the assets available for investment and contribute to inequities among public employees (such as ever-changing contributions and formulas, spiking pension benefits through the use of over-time, or allowing employees to retire and take a pension while getting hired for another position that will also pay a pension benefit). We are not addressing those kinds of practices or proposing reforms to fix the defined benefit system in this paper. We have concluded that defined benefit plans are not consistent with today’s demographic and market challenges,—and that defined benefit plans are

too vulnerable to political mischief. Our focus, instead, is on funding the defined benefit plans, paying down the unfunded liability and introducing a secure alternative system. But these unsound practices should be addressed by the Legislature.

32 Moody’s uses a discount rate for calculating liabilities tied to the yield on Aaa corporate bonds. Minnesota is paying off the pension debt via an amortization schedule that pushes off the cost far into the future, which significantly raises the cost of that debt. See Kim Crockett, Minnesota Taxpayers to Pay Higher Borrowing Costs Because of Pension Debt (Center of the American Experiment, August 2, 2013), available at http://www.americanexperiment.org/sites/default/files/article_pdf/Borrowing%20cost%20and%20 pension%20debt.pdf.

33 “Historical Annual Returns of the S&P 500 Index-Updated Through 2014,” Jim’s Finance and Investments Blog, January 10, 2015, at http://financeandinvestments.blogspot. com/2015/01/historical-annual-returns-for-s-500.html. Perhaps the state considers the S&P’s long term (more than 30 years) returns of over 10 percent when setting the ARR. After all, the pension obligations are long term. But when you look at the ARRs in the private pension sector, they dropped over the last decade. See Society of Actuaries, Report of the Blue Ribbon Panel on Public Pension Plan Funding (February 2014), available at https://www.soa.org/blueribbonpanel/.

34 Retirement Systems of Minnesota, Public Pensions: Myths and Facts (n.d.), available at https://www.minnesotatra.org/images/pdf/MythsFacts-combined%202012-13.pdf.

35 Gregory Zuckerman, “Big Investors Missed Stock Rally,” Wall Street Journal,

June 23, 2014, see graph showing public funds dropping to about 50% equities in 2013, available at http://online.wsj.com/articles/big-investors-missed-stock-rally-1403567478. The SBI asset allocation as of March 31, 2015 is about 62 percent equities, 24 percent fixed income and 12 percent “alternatives” with the rest in cash. (The goal is 20 percent “alternatives” though SBI has not met that goal presumably because not enough “alternative” vehicles have met SBI’s criteria). See Minnesota State Board of Investment, Combined Funds (Net of Fees) (June 31 2015), available at http://mn.gov/sbi/ Combined%20Funds%20Performance.html. By contrast, the average asset mix for private pension funds, which use lower ARRs and discount rates, and must be fully funded under federal law, is 41 percent in equities, 40 percent in fixed income and 20 percent in “other’ investments. See Milliman, “Corporate Pension Funding Study” (Milliman, 2013), available at http://us.milliman.com/Solutions/Products/Corporate-Pension-Funding-Study/; and Donald J. Boyd and Peter J. Kiernan, Strengthening the Security of Public Sector Defined Benefit Plans (The Rockefeller Institute, January 2014): p. 23, available at http://www.rockinst.org/pdf/government_finance/2014-01-Blinken_Report_One.pdf.

36 For a general discussion of this risk, see Pew Charitable Trusts & the Laura

and John Arnold Foundation, State Public Pension Investments Shift Over Past 30 Years (June 2014), available at http://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/Assets/2014/06/PensionInvestments06032014.pdf. What happens when there is another market downturn? Current assets total about $57 billion. An 18 percent loss (2009 loss) would reduce assets by over $10 billion.

37 Alaska offers a cautionary tale of pension reform and why it is critical to fully fund the remaining defined benefit system, and to pay off the unfunded liability. A new defined contribution for new employees does not solve the defined benefit problem. See Victor Nava, “Did Pension Reform in Alaska Fail?”, Out of Control Policy Blog, Reason Foundation, May 7, 2014), available at http://reason.org/blog/show/did-pension-reform-in-alaska-fail.

38 This recommendation comes from the accounting standards boards (GASB/ FASB) and across the political spectrum of pension experts in the academic and think tank world.

39 This report could also include state and municipal unfunded liabilities for OPEB (“other post-retirement benefits”) such as health care.

40 For current law, see Minn. Stat. § 352.03 Subd. 5, available at https://www.revisor. mn.gov/statutes/?id=352.03 (governing MSRS); and Minn. Stat. § 354.06 Subd. 2a, available at https://www.revisor.mn.gov/statutes/?id=354.06 (governing TRA). “The director must have had at least five years’ experience on the administrative staff of a major retirement system.” PERA’s statutory language is different: “The executive director must have had at least five years’ experience in an executive level management position, which has included responsibility for pensions, deferred compensation, or employee benefits.” Minn. Stat. § 353.03, available at https://www.revisor.mn.gov/statutes/?id=353.03.

41 Two examples are the annual cash bailouts of the school districts of Duluth ($6.5 million) and Saint Paul ($10.7 million). Why should the state taxpayer pay (potentially in perpetuity) for the bad management practices of these school districts? The practices that lead to the unfunded liabilities remain in place and in both cases, and retirees are scheduled to receive an increase in benefits (COLA to match TRA). If the state taxpayer had to be called to the rescue, surely a more respectable deal could have been reached.

42 If the municipality cannot afford to cover the gap, bankruptcy should be considered. While municipalities can declare bankruptcy, the state cannot under federal law. Amy Monahan, Understanding the Legal Limits on Public Pension Reform (American Enterprise Institute, May 2013): p.6, available at http://www.aei.org/ wp-content/uploads/2013/05/-understanding-the-legal-limits-on-public-pension-reform_104816268458.pdf.

43 Other options under consideration around the country include hybrids and cash balance plans. While these may be more politically attractive, they do not solve the problem and are, therefore, not sound policy. See Richard Dreyfuss, Fixing the Public Sector Pension Problem: The (True) Path to Long-Term Reform (Manhattan Institute, February 2013), available at http://www.manhattan-institute.org/html/cr_74.htm#. U7WjlPldW-g. Josh McGee from the Arnold Foundation testified before the LCPR on January 28, 2014 about retirement design. Josh McGee, Retirement Design: Much of What You Think You Know is Wrong [PowerPoint slides], Minnesota Legislative Commission on Pensions and Retirement Meeting, January 28, 2014, available at http://www.commissions.leg.state.mn.us/lcpr/documents/mtgmaterials/2014/mcgee_ presentation_012814.pdf.

44 The state already offers a variety of supplemental defined contribution plans for employees as well. Here is the link to the MNSCU plan: http://www1.tiaa-cref.org/tcm/ mnscu/plans/index.htm. TIAA is a lifetime benefit, so those wanting a steady stream of annuity income can buy it at any time. You can move all CREF accounts to TIAA when you want to lock in retirement income. See also Thomas Gais and Paul Yakoboski, Public Sector Pension Reform: Addressing Pressing Fiscal Realities from a Long-Term Perspective (TIAA-CREF Institute and Rockefeller Institute of Government, 2013), available at http:// www.rockinst.org/pdf/government_finance/2013-06-13-TIAA-CREF_Pension_Reform. pdf.

45 When the Legislature asked the pension plans in 2010 to study and report on a transition from the DB system to a DC or hybrid system, the pension plans issued a report that shut down the discussion by claiming that the transition costs were astronomical; the report has been criticized as confused and misleading. The critique reveals the conflict of interest. See Robert Costrell, “GASB Won’t Let Me” – A False Objection to Public Pension Reform (Arnold Foundation, May 2012), available at http://arnoldfoundation.org/img/LJAF-Policy-Perspective-GASB-Wont-Let-Me.pdf. Minnesota’s actuary and legislative study are called out by Costrell for being in error on pages 13-14; the NIRS, which Minnesota relies on for “expert” testimony is thoroughly discredited in a footnote on page 13, as it members are “virtually all public retirement systems.” In other words, they are not an independent resource. Also the “Transition Cost” objection has been thoroughly debunked here (page 30) and elsewhere. See Andrew Biggs, Josh McGee and Michael Podgursky, “Transition Cost Not a Bar to Pension Reform,” Pension & Investments, January 6, 2014, available at http://www. pionline.com/article/20140106/PRINT/301069999/transition-cost-not-a-bar-to-pension-reform; and Josh McGee, The Transition Cost Mirage: False Arguments Distract from

Real Pension Reform Debates (Arnold Foundation, March 2013), available at http://www. arnoldfoundation.org/sites/default/files/pdf/LJAF_Transition_Cost_Policy_Brief.pdf. (argues that the state can and should pay off debt early).

46 See endnote 44.

47 Michigan has the longest experience to offer. It moved new state employees to a DC plan in 1997. For an estimate of the savings and other benefits, see Richard Dreyfuss, Estimated Savings from Michigan’s 1997 State Employees Public Pension Reform (Mackinac Center for Public Policy, June 23, 2011), available at http://www.mackinac.org/ archives/2011/2011-03PensionFINALweb.pdf. See also Pension Modernization for the 21st Century Workforce, United States Senate (2012) (testimony of Andrew Biggs, American Enterprise Institute, Washington, D.C.), available at http://www.help.senate.gov/imo/ media/doc/Biggs1.pdf.

48 Private pensions generally do not pay COLAs.

49 For background, see Minnesota Office of the Legislative Auditor, Evaluation Report: Postemployment Benefits for Public Employees (January 2007), available at http:// www.auditor.leg.state.mn.us/ped/pedrep/postemployment.pdf .Would the reduction of the COLA for certain employees be constitutional? It is not clear but the 2010 Swanson decision held that the state, as the manager of the funds, had the discretionary power to change the COLA (not the base pension), Swanson v. State, Minn. District Court, June 29, 2011 No. 62-CV-10-05285.

50 This is recommended by GASB. For a discussion on how this saves money, see Josh McGee, The Transition Cost Mirage: False Arguments Distract from Real Pension Reform Debates (Arnold Foundation, March 2013): p. 5, available at http://www. arnoldfoundation.org/sites/default/files/pdf/LJAF_Transition_Cost_Policy_Brief.pdf. Minnesota will have to strike a balance between paying down debt and maintaining a high credit rating. In 2012, a level dollar payment was adopted for the (closed) Legislators funds. Omnibus Pension Bill, ch. 286, Art. 5, Sec. 1, 2012 Minn. Laws, available at https:// www.revisor.mn.gov/laws/?year=2012&type=0&doctype=Chapter&id=286.

51 Minn. Stat. § 475.52 Subd.6, available at https://www.revisor.mn.gov/stat-utes/?id=475.52; and Minn. Stat. § 475.58 Subd. 1 (7) and (10), available at https://www.revisor.mn.gov/statutes/?id=475.58. Minneapolis appears to be the only city that has done this so far but school districts are issuing bonds. See Minnesota Office of the State Auditor, Special Study: Other Postemployment Benefit Liabilities of School Districts in Min-nesota (March 31, 2009), available at http://www.osa.state.mn.us/reports/gid/2009/opeb/ OPEB_liabilities_report.pdf; Liz Farmer, “The not-so-sunny side of pension obligation bonds,” Governing Magazine, July 8, 2014, available at http://www.governing.com/top-ics/finance/gov-a-financial-tool-governments-should-use-with-caution.html; Alicia H. Munnell, Jean-Pierre Aubry, and Mark Carafelli, An Update on Pension Obligation Bonds (Center for State and Local Government Excellence, July 2013), available at http://slge. org/publications/an-update-on-pension-obligation-bonds.