Revolving door courthouses

Want to know why we’re worried about public safety? Ask the judges and prosecutors who keep returning thugs to our streets.

The largest mass shooting in recent history in St. Paul should never have happened. A shootout in the early morning hours of October 10th at the Seventh Street Truck Park bar left one person dead and 15 injured including the two perpetrators. In a morning tweet, St. Paul Police Chief Todd Axtell said he spoke with the 20-year-old victim’s family who were “absolutely devastated.” He promised that the police department “WILL bring justice” in the case. St Paul Mayor Melvin Carter said in a Sunday afternoon press conference, “we don’t accept things like this happening in our city,” and said he was “shocked,” “appalled,” and “heartbroken” over the brazen violence. But he shouldn’t have been.

It was St. Paul’s 32nd homicide in a record-breaking year – 35 as of December 9th. Throughout the Twin Cities, crime is overtaking headlines as street violence, robberies, and carjackings surge. Minneapolis homicides increased from 80 to 89 in the period between November 30th 2020 and November 30th 2021 according to the City of Minneapolis Crime Dashboard. Aggravated assaults increased from 2,791 to 2,926. The dangerous trend is due to many factors, but one that is foreseeable and at least somewhat preventable, is the number of criminals back on the streets after sentences are reduced. It is a plague of the revolving door, and what happened at the Seventh Street Truck Park bar is the deadly consequence.

According to prosecutors, Terry Lorenzo Brown, Jr., 33, from St. Paul entered the Seventh Street Truck Park bar armed with a gun that was illegally in his possession. Previous felony convictions include aggravated robbery, drug possession, aiding a robbery, and violating a no-contact order. Brown was ultimately charged with one count of second-degree murder and 11 counts of intentional attempted murder in the second degree.

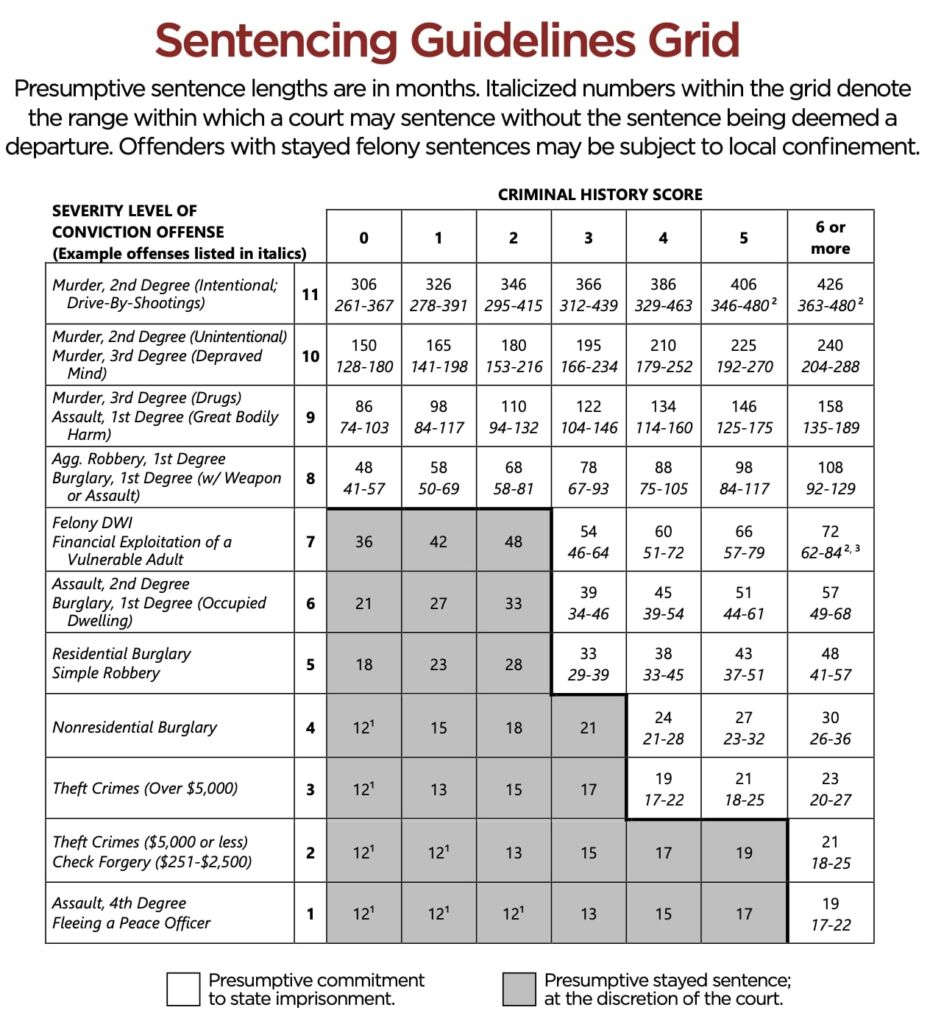

Brown was previously charged with five felonies between 2007 and 2019 for which state sentencing guidelines recommended prison sentences in four of those cases, but judges gave him lighter sentences allowing him to avoid prison. His record should alarm anyone concerned with their own safety and that of their community. In 2019 he was convicted of a felony, his second violation of a no contact order. After reviewing that case, with full knowledge of his past criminal activity and felony convictions, Judge Kathryn L. Quaintance sentenced him to 180 days in the Hennepin County Workhouse under supervised work release, a reduced sentence from the recommended 5 years in prison. However, he never showed up. Being in violation of the terms of his probation, Brown was again brought before the court in September of 2020. He was sentenced by Judge Sarah S. West to serve 210 days in the Hennepin County Workhouse, with a credit of 56 days for time already served. Instead of reverting to his initial sentencing term of five years in prison because he violated the terms of his probation, he was sentenced to serve less than one year under supervised probation. Brown was released back onto the streets with zero time served in prison.

Brown should never have been at that bar. He should have been halfway through a 5-year prison term in St. Cloud’s correctional facility.

These tragedies are exceedingly frustrating because they are not isolated incidents. Judges across the state impose softer sentences than those recommended by the sentencing guidelines. The latest data provided by the Minnesota Sentencing Guidelines show that Minnesota convicted 17,355 felons in 2019. Of those, 5,965 were recommended for prison, but 39 percent — 2,353 cases — had their sentences reduced to probation. The worst judicial offender in 2019 was Ramsey County, where 51 percent of guideline-recommended prison sentences were reduced, the highest rate of any judicial district in the state. Hennepin County recorded 34.5 of what they call “downward departures.”

For offenders who have been imprisoned for crimes occurring less than 28 years ago, the term of imprisonment is defined by Minnesota Statutes, section 244.101, known as the “two-thirds rule.” Convicted criminals with prison sentences will only serve two-thirds of the total executed sentence. According to a study by the Prison Policy Initiative in 2018, 123,000 Minnesotans were either incarcerated or under criminal justice supervision. Of those, a wide majority, 95,000 people, were on probation. In Minnesota, many felony cases result in mandatory probation sentences.

This means that most offenders will avoid jail altogether. Even when offenders are convicted of a felony with sentencing guidelines recommending prison, the judge may decide on a downward departure. But even if sentenced to a prison term within the recommended guidelines, a felon will only serve two- thirds of that time in prison before being released. It’s hard work for a convicted criminal to be sent to prison and serve hard time in Minnesota.

For perspective, Minnesota currently has the fourth-lowest state imprisonment rate in the nation with 176 people incarcerated per 100,000 residents, according to the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics for 2019. Massachusetts has the lowest rate at 133 per 100,000 residents. Louisiana is the highest with 680 per 100,000 residents. Wisconsin is right in the middle with 378 per 100,000 residents, more than twice the rate of Minnesota.

Ramsey County Sheriff Bob Fletcher told legislators at a hearing in October that mandatory minimums for gun crimes would help alleviate escalating violent crime. “What’s happening is because some in the court system and some in the attorney system don’t want to sentence people for that long; they’re generally pled down to something other than the actual gun offense. So somehow, we need to make sure we have some mandatory minimums on those gun offenses that aren’t pled down on a regular basis.”

The August 29th killing of Blake Swanson illustrates Fletcher’s point. The 20-year-old was allegedly shot and killed by Chris Jones at St. Paul’s Raspberry Island. Swanson and his friends frequented the site that summer before he was fatally shot in the neck and his girlfriend robbed while sitting in his car. In August of 2017, Jones was convicted of felony possession of a firearm and sentenced within the recommended Minnesota sentencing guidelines to 60 months imprisonment. However, because of the “two-thirds” statute, Jones was out on probation, in possession of a gun he was prohibited from having and shot Swanson to death.

As of November 30th, the Minneapolis Police Crime Dashboard reported 5,494 incidents of violent crime, compared to 5,083 incidents the same time last year, on pace to have the highest incidents of violent crime for the past five years. This is especially shocking compared to dramatically lower numbers of 4,322 in 2019 and 3,854 in 2018. The data show a similar, terrifying trend for homicides in the city. With 89 homicides through November 30th, Minneapolis has already surpassed the 2020 total. In that same time, St. Paul recorded 35 homicides, breaking the city’s record.

* * *

On November 12th, Robert Hall ran a red light at the north Minneapolis intersection of West Broadway and Lyndale avenues and crashed his gray Chevy Monte Carlo into a black Mercury SUV. Hall then shot Kavanian Palmer, a pedestrian who attempted to restrain Hall. Other onlookers stopped him as he attempted to carjack a woman’s car in an attempt to flee the scene. Palmer died, becoming the 84th homicide victim in Minneapolis this year. A subsequent search of Hall’s vehicle revealed he was also in possession of a .357 caliber firearm.

Hall, a 39-year-old career criminal from Golden Valley, whose record includes 23 prior convictions, never should have been on the street that day, nor owned the two guns he possessed at the time of his arrest. Sentencing guidelines recommended 21-month prison sentences for felony state lottery fraud and felony drug possession from December 2020. This came after he was convicted of felony drug possession in 2016 and three counts of felony domestic assault charges in 2011, 2012, and 2013. Instead, Judge Marta M. Chou ignored the guidelines and released him into Hennepin County’s Model Drug Court. He was out on probation at the time he allegedly shot and killed 21-year-old Palmer.

Judge Chou did not respond when reached for comment about her decision. However, a communications specialist at the state court administrator’s office said the referral to probation was made per an agreement between the prosecutor and the defense attorney. The judge could not comment about the killing of Palmer per pending case rules.

It isn’t just violent criminals making headlines. County attorneys are also in the spotlight for not prosecuting crimes already on the books. Ramsey County Attorney John Choi announced in September that his office will no longer prosecute cases in which the charge comes from a non-public-safety traffic stop, claiming those stops disproportionately target people of color. County attorneys set the tone for law enforcement in the Twin Cities and surrounding suburbs, and policies in place in the metro area appear to be influencing communities across Minnesota. “When I talk to my local law enforcement, crime is migrating from the urban area into rural Minnesota and one of the reasons why my local law enforcement feels this is occurring is the lack of prosecution,” said Scott Newman, a senator from Hutchinson, speaking to his fellow committee members and representatives of Minnesota law enforcement in a Judiciary and Public Safety and Finance committee hearing in October. He expressed disappointment that Choi was a no-show for the hearing. “I candidly am very disappointed he’s not here because it is his policy that he has instituted in Ramsey County, his jurisdiction, that in large measure is why we’re here today.”

Declining to prosecute cases stemming from traffic stops misses more dangerous offenses, according to law enforcement officers. Choi “is asking departments to direct officers to stop enforcing laws that he personally disagrees with,” says Allison Schaber, president of the Ramsey County Deputies’ Federation. “This new policy will create missed opportunities for officers to remove dangerous criminals, drugs, and guns from the streets.” Choi’s new policy will embolden offenders to commit crimes, she added. “Less accountability for criminals means more people will continue to be victimized.”

Choi’s policy is “a slap on the face to victims of crime.” Brian Peters, executive director of the Minnesota Police and Peace Officers Association told the same Senate committee. “Those that break the law, particularly at a felony level won’t even get a slap on the wrist and [are] left to commit more crime and more serious offenses. Reduction of crime and public safety for all should be our focus as the crime rate escalates.” Peters continued, “When people speak of not prosecuting crimes or reducing sentences, a result is emboldening those who choose criminal activities. This does not keep people safe.”

* * *

Hennepin County will soon decide if it will follow Choi’s lead, perhaps delayed in part by the fact that Hennepin County Attorney Mike Freeman has announced his retirement and will be replaced in the 2022 election. The candidates have spoken publicly about incorporating transformative progressive change into the role of law enforcement, “There’s never been a better opportunity for change in my 31-year career,” candidate Mary Moriarty said in an interview with Minnesota Reformer, pledging that under her leadership the county attorney’s office would place more focus on alternatives to prison.

Current Minnesota House Majority Leader Ryan Winkler, also running, told KARE-11 News that “people are really hungry for somebody who can pull us together around a progressive vision for public safety in Minneapolis and surrounding suburbs.” Another candidate, Assistant Ramsey County Attorney Saraswati Singh, pledges to expand the role of drug treatment courts as an alternative to prison, prioritize addressing racism and systemic racism, and update the current drug charging policy focusing on treatment and incarceration alternatives, according to her campaign website.

This rhetoric follows the lead of cities that elected prosecutors prioritizing criminal justice reform and “Restorative Justice.” In San Francisco, District Attorney Chesa Boudin, elected in 2019, pushed to close jails and focused on systemic racism in the criminal legal system instead of prosecuting actual criminals. Now, the city’s rampant crime has become a national talking point. The deaths of two pedestrians, killed by a vehicle driven by a paroled felon, started a recall effort by outraged residents. Voters will now decide if Boudin will keep his position when his job is put to the vote in June.

Senator Warren Limmer related the concerns of his constituents at the end of the Ocotber Minnesota Senate committee hearing, “Everyone is coming up to me with the concern ‘what are you guys doing about prosecutors not prosecuting crime?’ Police officers now, don’t feel they should arrest someone because the prosecutors aren’t even going to prosecute. This is an acute problem in the metropolitan area that is moving, sprawling into outlying areas. Even the Star Tribune ran with the headline, ‘Crime But No Punishment.’ We do have the power to react to crime. That is the focus of our attention.”

Unfortunately, this is not a concern of a growing number of Minnesota’s judges and prosecutors.