Solving the unsolvable

A first-hand account of a Minneapolis murder case and what we can learn from it now.

This is the story of an 11-year-old boy cut down by a bullet fired during a gang shootout in North Minneapolis in 1996. His death helped ignite a response that brought about real change — change that led to a sustained reduction in violent crime in Minneapolis and beyond. Tragically, those efforts and the results have been lost over time.

Stolen Innocence

Byron Phillips was a young African American boy growing up in North Minneapolis in the 1990s. He lived with his mom and siblings near Golden Valley Road (GVR) and Newton Avenue North. Violence permeated his neighborhood, such that gun shots and violence were commonplace — a reality to which few can relate, but one that Byron was sadly accustomed.

On Sunday evening of June 2, 1996, Byron joined two close friends to play basketball at a neighbor’s house. As a summer rain shower moved in, the boys moved up to the front porch of the house talking and kidding each other. Little did they know their lives were about to change forever.

About a year earlier tensions began between two gangs: the Shorties Taking Over (STOs) from Byron’s neighborhood, and the Bogus Boys from South Minneapolis. Dice games gone bad, the stealing of a gold chain, and a group of young men ill-equipped to resolve conflict led to escalating violence between the groups.

The STOs and Bogus Boys were rogue and had been taught through interaction with an ineffective criminal justice system that there was little to no consequence for violence and thuggery. They moved around town selling dope, “pimping out” girls, shooting at rival gangs, and reveling in being held unaccountable for their antisocial behavior. It was common for most of these gang members to have dozens of arrests by their early 20s, with one member of the Bogus Boys having nearly 70 arrests without significant incarceration. Their lives were about to change forever as well, albeit in a completely different way.

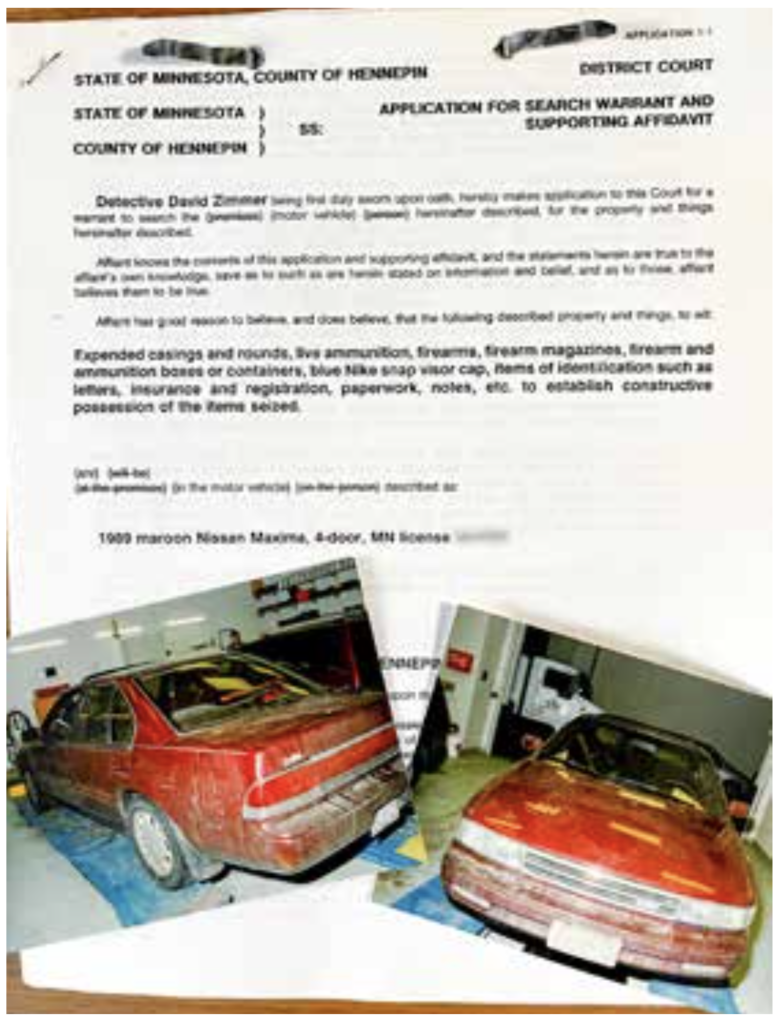

By June 1996, the conflict between the Bogus Boys and STOs led to a “shoot on sight” mentality — meaning they shot at each other whenever they came into contact with complete disregard to anyone in the area. The Bogus Boys decided to take it a step further. They began to regularly drive through the North Minneapolis neighborhood of the STOs hoping to catch them off guard. It was common for the Bogus Boys to use a variety of cars to carry out these rival gang “hunts” so they could drive around undetected by the STOs and police. This involved using so-called rental cars. But in this case, a “rental” was a car from a drug addict that handed over the keys of their car for a small amount of crack, or a car belonging to a girlfriend or “cousin” that hadn’t yet been registered in their name. If police tried to stop them, gang members simply fled and dumped the car without fear of the car being traced back to them. (This type of criminal use of cars is what fuels many of the car jackings and car thefts that have occurred in recent years).

In the days before Byron Phillips’ murder, violent shootouts between the STOs and Bogus Boys occurred with regularity. STO member “Junebug” was targeted several times, but came out unscathed. On Friday, May 31, he was chased and shot at by several Bogus Boys and ended up shooting Bogus Boy “Stoney” in the jaw. On Saturday, he was again chased and shot at by several Bogus Boys and ended up shooting “Snyp,” another Bogus Boy in the neck, partially paralyzing him. After each was shot, they were dumped outside the ER before their associates fled.

In all, there were at least six shootings between the Bogus Boys and STOs in Byron’s neighborhood over the four days preceding his death.

On Sunday June 2, Stoney was released from the hospital. He met up with Bogus Boys “Cool,” “Tay,” and “Dave” as they gathered in North Minneapolis with several guns. They decided to use Tay’s mother’s maroon sedan to hunt for Junebug. At one point Dave and Stoney were dropped off on foot, while Tay and Cool remained mobile in the maroon car. A Minneapolis Police Department officer drove past Dave and Stoney. Stoney got nervous and ditched his gun near a tree which didn’t escape the officer’s attention. The officer took the two into custody, recovered the gun, and booked both in the Hennepin County Jail.

Junebug was staying at his sister’s house situated a block from where Byron and his friends were playing basketball. He decided to walk to Sam’s Market on Golden Valley Road and Penn Avenue North. When the rain passed shortly after 6 pm, he began walking back to his sister’s house. As he crossed Newton Avenue, next to the front porch where Byron and his friends were sitting, 10 shots rang out as a car sped by. Junebug ran south in the alley and took refuge in his sister’s house, once again unscathed.

A combination of witness accounts suggests the shooters’ car was maroon, and the driver and passenger were both shooting at Junebug. The passenger, later determined to be Cool, wildly fired at least seven rounds as he pointed his gun out the passenger window and over the top of the car.

The three boys on the porch sat stunned as the shots rang out with at least one bullet hitting the stucco house, creating a spark. Almost immediately, Byron grabbed his side and said he’d been hit. His friends thought he was joking, but when he fell backward off the railing, they realized he was seriously hurt. Police who responded within a minute located Byron lying behind the shrubbery. They noticed blood coming through his Cat in the Hat t-shirt and located a single gunshot entrance wound on his abdomen. The young boy was unresponsive, and paramedics were unable to revive him.

Byron was pronounced dead directly across the street from his house, as his mother looked on in disbelief.

The investigation

In 1996, Minneapolis was hurting. Gang violence was exploding throughout the city. A record 98 people had been killed the previous year, and the pace wasn’t slowing. Even an article in the New York Times famously referred to Minneapolis as “Murderapolis.”

Unlike today, the police department was properly staffed, but was still struggling to keep up with the high volume of work. MPD leadership and Hennepin County Sheriff Pat McGowan, a former MPD officer and state senator, reached an agreement to help alleviate the caseload. The sheriff’s office sent two detectives to the MPD Homicide Unit. Being young and willing, I was pleased to be chosen to assist. What was officially a six-month temporary assignment turned into an unofficial partnership that lasted several years. My experiences associated with the homicide unit represented the best years of my career and certainly the most meaningful.

My sheriff’s office partner, “Slick” and I were enthusiastic about the opportunity. We were both seasoned narcotics unit investigators and were adept at writing reports, executing search warrants, and conducting interrogations — all required skills in the business of murder investigations.

By June 1996, Slick and I had proven ourselves in the unit and were put into the rotation to be assigned the next murder. Sunday June 2 we received word of Byron’s murder and hit the ground running with the first case that was solely ours.

We weren’t expecting the chaos that followed. Byron’s age and the on-going violence in North Minneapolis brought conditions in the city to a boil. The police chief, mayor, city council, citizens, activists, the media — everyone was demanding answers, and the pressure to solve this murder was palpable.

Cases involving gangs are arguably harder to solve. Dysfunctional gang culture, layers of deceit, arrogant disrespect for order, and the intimidation of witnesses all combine to stifle information and progress. Slick and I covered all the traditional investigative duties such as taking statements, interrogating suspects, canvassing the neighborhood for reluctant witnesses, and executing search warrants. Despite the effort, it became clear that a traditional investigation was unlikely to solve this case.

It took several weeks to confirm the identity of Junebug and locate him. When we finally tracked him down, he initially denied he was the intended victim. He later confirmed he was the target, but provided information that was later proven false. All in all, Junebug was as bad as the Bogus Boys who were shooting at him. He ended up charged and convicted for the shootings of Snyp and Stoney. He never cooperated to the point where the county attorney felt comfortable using him as a witness. Junebug’s role and reluctance to cooperate underscores the difficulty of gang investigations.

The casings left at the scene by the shooters were important pieces of evidence. Examination of these casings confirmed there were two guns involved.

In addition, when we asked the ballistics expert to compare those casings with other shootings the Bogus Boys were suspected of committing, we were able to link one of the guns used in Byron’s murder to several of the shootings that occurred over the weekend between Junebug and the Bogus Boys. This level of scientific evidence was cutting edge for the time and later proved to be a significant part of the case.

A month after Byron’s death came a turning point: Cool held a gun to his sister’s head during an argument, she called the police, Cool was arrested, and a gun seized. Slick and I worked with the ATF to trace the gun back to a female named “Shawn.” We executed a search warrant on Shawn’s apartment and found evidence that she had been purchasing several guns for the Bogus Boys. Shawn was arrested, charged, and federally convicted along with Cool. In addition, we were able to get Snyp and Stoney charged in connection with several shooting for which they were imprisoned. The dominos were starting to fall.

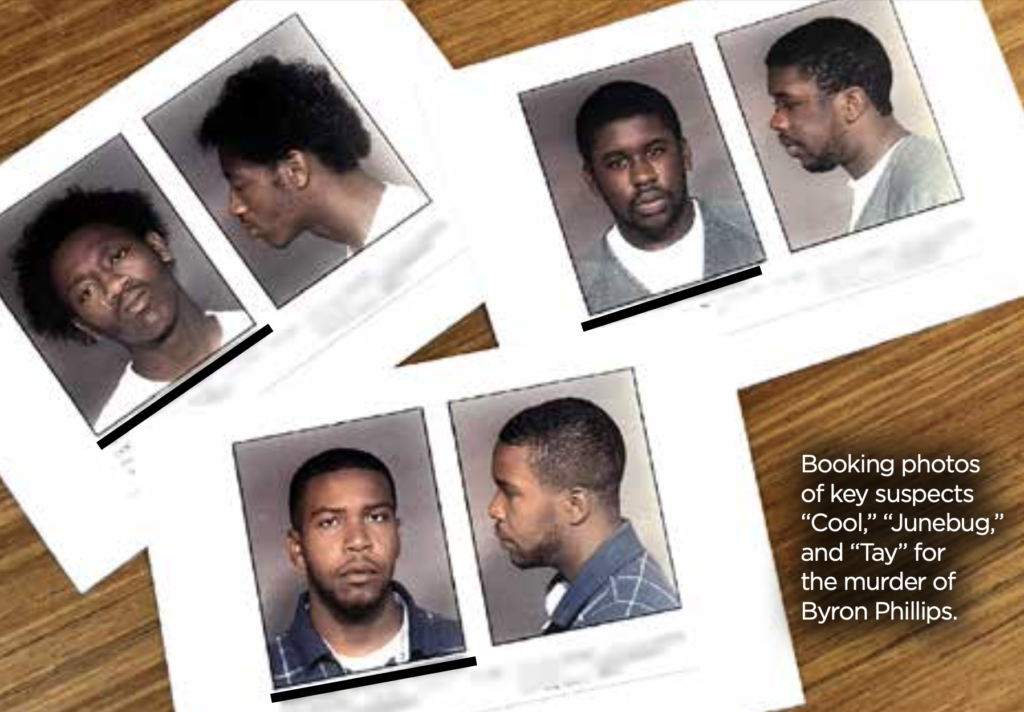

Over the summer and fall we received dozens of tips all leading us to believe Tay and Cool were Byron’s shooters. We went back to many of the Bogus Boys repeatedly and shared just enough information to convince them we knew what had happened and that people were talking — even some of their fellow gang members. Eventually this tactic served to turn some of them on one another. But we still didn’t have enough to charge Cool and Tay with Byron’s murder.

As time passed, our assignment to the MPD homicide unit came to an official end but we kept the case. I was fortunate to be re-assigned as a Narcotics Unit supervisor, and my boss at the time understood that it was more important to solve the murder of this 11-year-old boy than focusing on narcotics cases. He gave me as much time as I needed to continue to work on Byron’s murder.

However, it’s a tragic fact that the more time that passes after an unsolved murder, the more difficult it is to solve. And despite our best efforts, the case went dormant in the fall of 1996. That didn’t sit well with me. I spent an inordinate amount of time thinking about Byron outside of work. I came to the realization that if the case was going to be solved, we needed to go on the offensive.

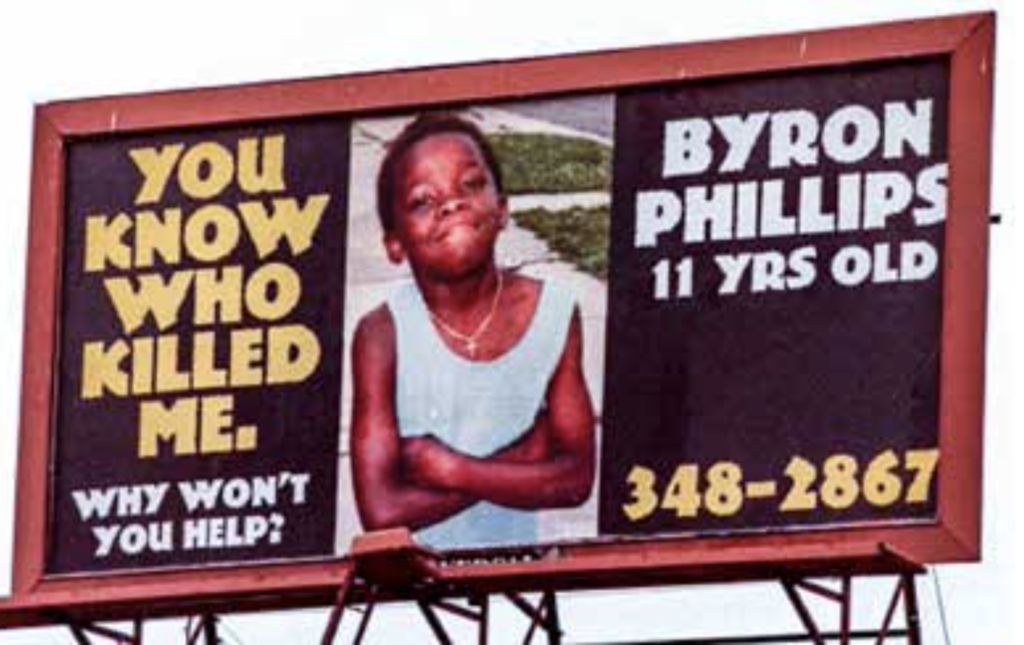

We knew the Bogus Boys claimed Peavey Park as their territory in south Minneapolis. There was a large billboard that sat atop the buildings overlooking the park at Chicago and Franklin Avenues. We decided to try to erect a billboard with Byron’s face staring at the Bogus Boys 24 hours a day. Byron’s mother was supportive and gave us a photo of her son in a heartbreakingly innocent and playful pose. We came up with the verbiage, “You know who killed me, why won’t you help.” It was bound to play on the emotions of someone who knew what happened. Now all we needed was funding.

Naegele, the billboard owner, stepped up and provided the space and artwork for free. The billboard went up in the summer of 1997. For a few months, very little information came in. Then a woman named Vanessa called who lived near Peavey Park. She told me that looking at Byron’s face each day haunted her. She wanted to meet and tell me what she knew about his murder but was concerned for her safety. After more time and encouragement, Vanessa finally agreed to a meeting. The information she had was significant.

Vanessa had been at home in bed the evening of June 2, 1996. Her nephew, Lemon, was a Bogus Boy associate and was staying with her. During the late evening, Cool and Tay had come into her house to meet with Lemon. They were excitedly talking about “dumping” on the STOs on the northside, unaware of Vanessa’s presence. Cool said they may have shot a kid by mistake. Cool and Tay asked for a change of clothes and wanted Lemon to accompany them back up to the northside.

Vanessa’s information tipped the scales for the county attorney, and a grand jury was convened. Stoney ended up cooperating against the others. He gave critical information that placed the gun that had been used in several of the shootings that fateful weekend in Cool’s hands just before Byron’s murder.

Over several months we gathered testimony from Vanessa, Lemon, Stoney, and others establishing probable cause that Cool, Tay, and Dave had attempted to kill Junebug and in the process had killed Byron Phillips. A trial was held nearly three years after Byron’s death, and all three Bogus Boys were convicted for their roles in the murder and sentenced to prison.

The aftermath

By the late 1990s, a half dozen or more Bogus Boys had been imprisoned, a few others had died or were seriously hurt in subsequent shootings, and the rest were left unsure who they could trust. The demise of the Bogus Boys by that time was a significant blow to gang violence in Minneapolis.

Concerted efforts by police, prosecutors, courts, and corrections during this time led directly to a 22-year decline in violent crime. The formula was simple: identify, prosecute, and imprison those carrying out the violence in our streets. Public safety thrived during this period, and Minnesota experienced some of its most peaceful years on record.

Unfortunately, it’s obvious many of the lessons learned when we battled our way out of the “Murderapolis” brand have been disregarded as violent crime once again explodes in communities across the Twin Cities.

Twenty-seven years later, Byron’s old neighborhood has descended back into violence. Many of the community leaders who said, “Enough is enough” after Byron’s murder can be found at the vigils of murder victims in 2023 saying, “Enough is enough.”

Sadly, no one seems willing to acknowledge that as long as violence is excused and scapegoated, “enough” will just remain an empty slogan.