Stop helping us!

The surreal prices and disappearing number of Minnesota’s childcare providers hurts parents, children and the communities they live in. And it’s caused by the government.

Let’s say you’re a young single mom living in Greater Minnesota, looking to find a childcare provider for your infant while you search for a much-needed job. You’ve heard the horror stories about the growing scarcity of providers and the sky-high prices of care, if you’re lucky enough to find it. You have friends who’ve been forced to drive 30 minutes out of their way — twice a day — to get to their provider, and some parents spend months on waiting lists to secure an open slot. You’ve even heard about the couple who timed the arrival of their new baby to coincide with a pre-arranged vacancy.

Minnesota’s high prices and declining vacancies have made childcare a nightmare.

And then you did the math: A single parent family at the median income level in Minnesota should be prepared to spend two-thirds of their wages to enroll an infant in a childcare center for one year.

Your decision is probably an easy one. You won’t join the workforce. You’ll stay at home with your baby, likely needing some kind of government assistance or taking on work-from-home freelance gigs that pay poorly and provide no benefits. And that local employer who is starved for access to employees will have one less person to help contribute to the economic development of your community. And your daughter, without the intellectual and social stimulation of high-quality childcare, will miss out on development programs that would make her ready for school.

It’s not just single parents who suffer. The price of childcare impacts the family budget of most working parents as much as a second house payment.

The steadily rising price of childcare spiked in the last two years in the face of COVID-19 restrictions and the shrinking labor market. In 2019, the average American family spent $11,836 to send one infant to day care, according to Child Care Aware, a national childcare research and advocacy group. A family with two children –– one infant and one 4-year-old — could expect to pay $21,460. Parents in Minnesota faced an even nastier childcare marketplace. They paid on average $16,164 –– or $1,347 per month –– to keep an infant in a day care center and $28,611 for both an infant and a 4-year-old.

Certainly, these costs depend on region. If you are in rural Minnesota, chances are you will likely pay less than someone living in the Twin Cities. This is because of differences in the cost of living. Things like labor and housing are less expensive in the rural areas compared to the big cities, which saves providers money enabling them to charge lower tuition. According to data from Child Care Aware, parents can expect to pay at least 30 percent less in rural Minnesota compared to the Metro region for home-based childcare. For center-based care, parents can expect to pay 20 percent less in rural Minnesota than in the Twin Cities. Unfortunately, parents in rural Minnesota are also likely to have lower incomes. So, Minnesota parents are squeezed when it comes to childcare, regardless of where they are in the state.

Ironically, the culprit behind these soaring prices and low availability is not a cabal of nefarious providers banding together to exploit a vulnerable market. Hardly. It’s the government.

The “shortage” problem

This scarcity of childcare vacancies can be traced directly to the shortage of licensed providers. In 2019, for example, Minnesota childcare facilities had capacity to care for 227,368 children, according to the Minnesota Department of Human Services (DHS). However, the number of kids under six who potentially needed care –– i.e., kids whose parents were in the labor force — was 310,767 according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey –– a shortage of 83,399.

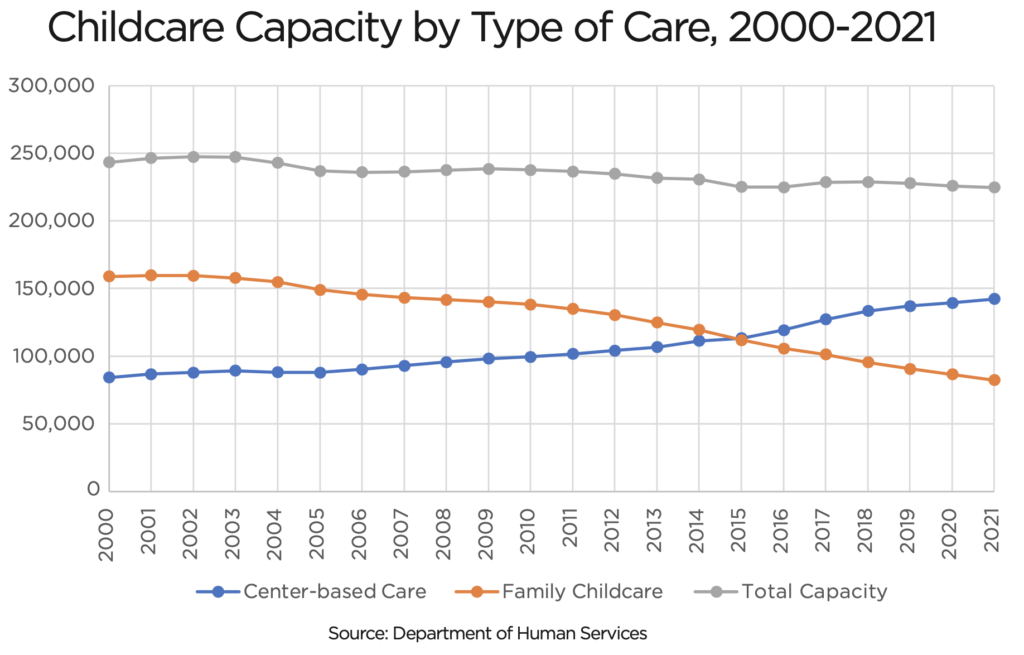

While this shortage afflicts the whole state, in rural Minnesota it is more acute. In rural Minnesota, the childcare industry is traditionally dominated by small home- based providers — or family childcare providers — who usually work out of their homes and are only allowed to take care of 10 or fewer children. Home-based providers, however, have been leaving the industry in droves. Data from the Department of Human Services show that while home-based childcare made up nearly one-third of the total childcare capacity in Minnesota in 2000, it only made up about 37 percent of total capacity as of 2021. Home-based childcare capacity has been nearly halved between 2000 and 2021.

Luckily for the metro regions, home-based providers who have left the industry have been replaced by licensed childcare centers. Centers are usually larger and are allowed to accommodate larger numbers of children. Centers are also mainly based in locations other than the provider’s home, so there are no limits to how big they can be.

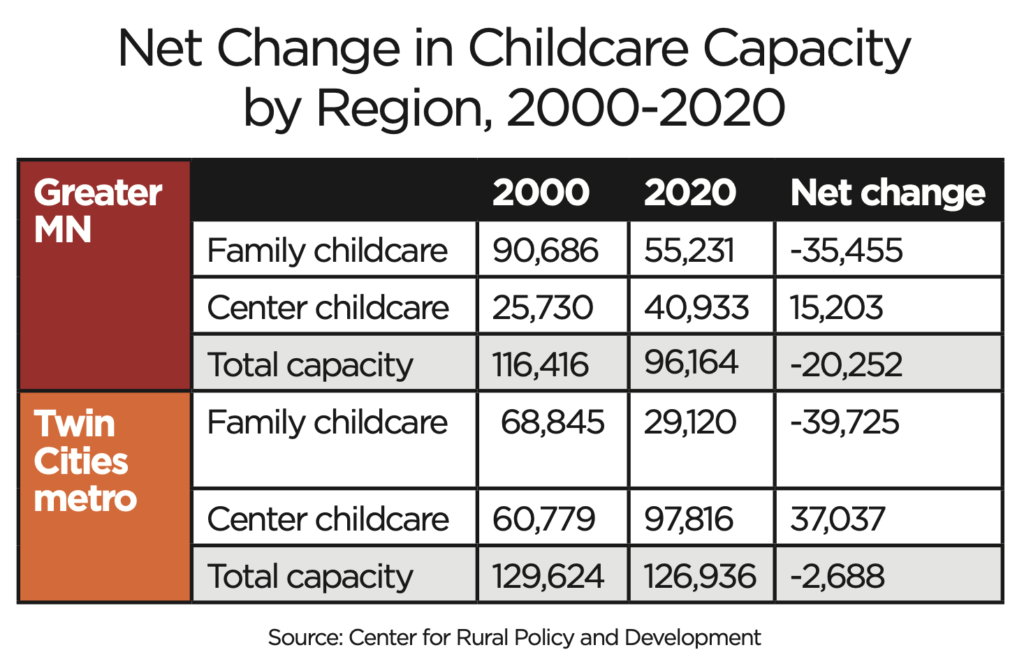

Unfortunately, in rural Minnesota centers are not easy to come by. This is largely because big, licensed day care centers are expensive to run and set up. To recoup their investment, providers rely on charging high tuition and enrolling higher numbers of children. But populations in rural Minnesota are sparse, meaning fewer children per given area of land. Moreover, parents have lower incomes compared to the ones in big cities. This makes setting up a licensed care facility in rural Minnesota financially unsound in most cases. So even though the share and number of licensed childcare centers has increased, that growth has only been concentrated in the metro where populations are more densely packed, and parents can afford the high tuition. According to the Center for Rural Policy and Development, between 2000 and 2020, rural Minnesota lost over 20,000 childcare slots with no replacement.

The exit of home-based providers is deeply problematic for many reasons. For one, centers are usually more expensive than providers working out of their own homes, and even more so for younger children like infants and toddlers. So home-based providers tend to be a common option for poorer parents. Moreover, centers are usually only open during regular working hours, which means that parents who work on weekends and have irregular schedules must find other arrangements. Also, centers usually follow standard curricula, something which may not satisfy the preferences of ethnic parents who want providers that share their culture or parents who would like religious-based instruction. And since centers mostly set up shop in densely populated areas like the Twin Cities metro, they also cannot accommodate parents in rural areas.

The COVID-19 crisis

The childcare crisis has been an issue before the pandemic, but events during the COVID-19 economy have made it worse. One, parents who lost jobs and had little need for day care or could not afford it pulled their children out of day care. Some parents also wanted to protect their kids from contracting the virus, so they did the same. As a result, providers lost money because they were caring for fewer children compared to the time before the pandemic. Providers were also required to keep group sizes small to prevent the spread of COVID-19, limiting enrollees and therefore income. To add insult to injury, providers saw their costs rise while their revenues were drying up since they had to spend more money on cleaning materials.

To illustrate how heavy these losses were, the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis did an analysis looking at a hypothetical childcare center. According to their calculations, based on the state’s 10-person group limit, a day care center that normally serves 104 children — 16 infants, 28 toddlers, and 60 pre-school kids –– would have to reduce their enrollment by 47 and only take care of 57 children. This means that the center lost $17,943 in monthly revenue.

Certainly, government programs like the American Rescue Plan Act and the Paycheck Protection Program helped some providers weather the pandemic. However, some providers have had to dip into their savings or take out high interest loans. Worse yet, some have been forced out of business. This exacerbates what was already a nightmare for parents, especially those with low-incomes, and those in Greater Minnesota.

According to the Center for Rural Policy and Development, Minnesota lost more than 4,000 childcare slots between 2019 and 2020, with in-home providers making up an estimated 97 percent of the total loss.

What government can do

Minnesota’s regulators and legislators rarely consider how regulations contribute to high-priced care, preferring to focus on increasing subsidies and expanding publicly funded childcare programs. But this crisis has been caused by burdensome child-staff ratios, hiring requirements, and a stringent regulatory environment, all caused in the spirit of “protecting” children.

So, to tackle the childcare issue more sustainably, lawmakers need to address factors that raise the cost of providing care.

Loosen child-staff ratios and group size limits

At a day care center, children are usually divided into groups. The person in charge of giving primary care to each group of children and designing day to day programs is considered a lead caregiver. In Minnesota, childcare workers with teacher qualifications are the designated lead caregivers.

The number of caregivers required per group of children is dependent on staff-child ratio requirements. For Minnesota, the maximum number of infants — age 6 weeks to 16 months — that can be in one group is eight. And for every four infants, centers must have one staff person. This means that centers must have two staff workers per group of infants. However, other states like Colorado, Arkansas, and Mississippi allow more infants per staff person and more infants per group.

Requiring staff to take care of a small number of children increases the cost of providing care, and these costs are passed on to parents. To alleviate costs, legislators should consider allowing larger group sizes as well as more children per worker. Findings from American Experiment, for example, show that if Minnesota laws were changed to allow five infants per staff, center tuition for infants would be approximately $2,811 less. For 4-year-olds, allowing one more child per worker would make center tuition less expensive by about $450.

In addition to allowing staff to take care of more children in each group, legislators should also consider changing the definition of infants to only include children between 6 weeks and 12 months. Generally, older children have greater staff-child ratios and group sizes. In Minnesota, for example, childcare centers can have 7 toddlers — defined as children between 16 to 33 months — per staff, and 14 toddlers per group. States where the age cut-off for infants is low — like 12 months — usually put slightly older children in bigger groups.

In Minnesota, however, the cut-off age for infants is much higher at 16 months. This means that while children between 12 and 16 months are considered toddlers in other states, and therefore face looser restrictions, that is not the case in Minnesota. If legislators lower the cut-off age for infants to 12 months, it will mean that children between 12 and 16 months will be defined as toddlers, allowing centers to put them in bigger sizes and thereby reducing the cost of providing care — savings that could be passed on to parents.

Loosen hiring and training requirements

To be employed as a teacher at a day care center in Minnesota, someone with a high school diploma must have 4,160 hours of experience as an assistant teacher and 24 quarter credits from an accredited post-secondary institution. Assistant teachers must have a high school diploma and 2,080 hours of experience as an aide or student intern and 12 quarter credits from an accredited post-secondary institution. Taken together, a childcare teacher at a center requires a high school diploma plus more than 6,000 hours of experience and 24 quarter credits of post-secondary education.

Other states, however, only require childcare workers who are designated as teachers or lead caregivers to be over 16 years old and undertake training before looking after children. Such training may include topics in child development, safe sleeping methods, as well as First Aid and CPR.

According to research evidence, stringent hiring requirements have little to no effect on quality. However, these requirements do increase the price of childcare. Findings from American Experiment, for example, estimate that requiring childcare workers to have a high school diploma raises the cost of center tuition by about $1,920 for infants, and $1,300 for 4-year-olds. Moreover, those costs double when post-secondary education is added.

Legislators should loosen Minnesota licensing laws and ensure that hiring requirements instead emphasize on-the-job training and other mechanisms like apprenticeships. This would enable workers to get the knowledge and experience they need without incurring heavy education costs. Considering that the childcare industry is a low wage industry, it makes no economic sense to require workers to spend time and money to fulfill the high bar of requirements as college credits for such low wages. It is no wonder that providers report that qualified workers leave childcare to go to work at places like McDonald’s, which have no skill requirements but pay the same wages, if not more.

Loosen administrative rules

Administrative rules sometimes reduce flexibility and increase compliance costs contributing to the rising cost of care. For instance, as previously mentioned, the Minnesota DHS requires that the person in charge of a group of children — also known as the lead caregiver — should have the qualifications of a teacher.

Unfortunately, teachers are more expensive since they face more stringent hiring requirements compared to other caregivers like aides or assistant teachers. And due to this rule, day care centers are unable to use equally capable, but more affordable workers with less educational qualifications like assistant teachers or aides as lead caregivers.

Allowing day care centers the flexibility to use other skilled workers like aides or assistant teachers as lead caregivers would lower costs for providers without lowering quality, especially considering that assistant teachers in Minnesota face more stringent requirements than do lead caregivers in many states.

Conclusion

If the childcare crisis persists, more and more Minnesota parents will be unable to work, forced to stay home and provide care for an infant or child, and businesses will not be able to find workers. Not to mention that children will miss out on important development programs. The childcare crisis is detrimental not only to parents, children, and families but the entire economy.

To address the issue, legislators need to realize that it is government action that has been at the heart of the crisis. Minnesota rules strictly limit the number of children that workers can take care of. In addition to that, our state also places higher education standards for teachers compared to other states. These stringent rules do not come at zero cost. Higher education standards raise labor cost, as do small group sizes and strict staff-child ratios. These are costs that are then passed on to parents through higher tuition. It is high time lawmakers stop throwing more money at childcare and start dealing with the real culprit.