System(ic) failure

Dramatic recent damage to Minnesota’s law enforcement institutions has led to a corresponding rise in crime. Past experience tells us how we can turn this around.

The growing number of Minnesotans who are frustrated and distressed by the stunning decline in public safety in the state need only look to the 1990s for a path back.

Unchecked gang activity in the Twin Cities in the mid 1990s sparked such a significant spike in violent crime that the New York Times dubbed us “Murderapolis.”

“Something’s wrong, and I’m going to say it…We’ve got a crisis in the African-American community, and we’ve got to deal with it….We’re going to stop people for minor traffic violations, and we’re going to check them for illegal guns.” That was a statement from Minneapolis Mayor Sharon Sayles Belton to Newsweek in 1995, amidst a string of street violence that plagued the city.

Outrage over the level of violence coalesced into a resolute coalition of citizens, community activists, clergy, police, prosecutors, judges, and politicians to attack the problem head on. This coalition provided a mandate to police and the criminal justice system to go after criminals and stop the violence. A proactive, targeted, and sustained effort took place by law enforcement, prosecutors, the courts, and corrections to go on the offensive and restore order. Federal law enforcement and courts added their weight, too. Through the efforts of several task forces and coordinated initiatives, many of the most active criminals were incarcerated. Those not incarcerated got the message — Minnesota was no longer hospitable to crime.

This unambiguous civic mandate to police and the criminal justice system represented the beginning of an impressive 22-year decline in Minnesota’s crime rate.

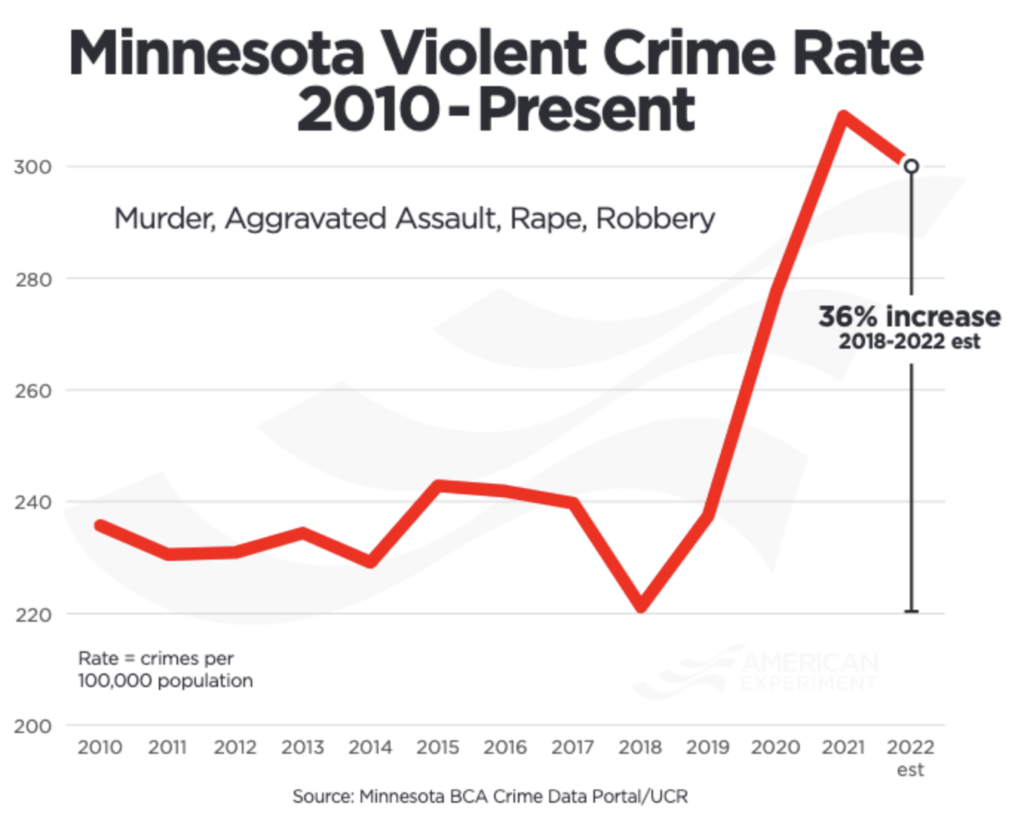

Unfortunately, since 2018, Minnesota has seen dramatic increases in crime, especially violent crime. In 2020, Minnesota officially became a high crime state, surpassing the national average for the first time in the state’s history.

How did we get here?

The other lesson of understanding our current problem is to examine how we got here. While the rise in crime is a complex problem that cannot be blamed on any single factor, the Defund the Police movement championed by Black Lives Matter (BLM) has arguably pushed our criminal justice system away from the community’s long-term best interest, especially in predominantly black neighborhoods that bear the brunt of recent chaos.

BLM’s history

Black activists founded BLM in 2013 after a Florida court acquitted Hispanic security guard George Zimmerman of criminal charges in the shooting death of Trayvon Martin, a 17-year-old black youth. BLM’s reaction gave voice to the frustration felt by many that the criminal justice system valued black people less than white people. The movement began focusing on fatal encounters between law enforcement and black suspects.

BLM intensified its response to subsequent in-custody or officer-involved deaths. It effectively influenced the decision-making process in these cases by targeting prosecutors, judges, politicians, and police leaders.

The BLM movement began to emerge in Minnesota in 2015 after a white officer killed Jamar Clark, a black man who had interfered with police officers and an ambulance crew trying to aid a woman whom he had reportedly assaulted. During a struggle, Clark wrestled with the officers and attempted to take a holstered handgun from one of them. The other officer fired a single round killing Clark and stopping the threat.

BLM in Minneapolis led an 18-day “occupation” of the Minneapolis Police Department’s 4th Precinct. Protesters blocked Plymouth Avenue and encircled most of the precinct station, holding bonfires in the street and pelting the building with rocks and bricks. Minneapolis officials declined to interfere with the protests. Instead, they ceded the street to activists and bussed officers into work at the precinct for weeks. It set a precedent, demoralized officers, and emboldened activists.

County Attorney Mike Freeman added to the chaos by declining to impanel a grand jury to make a charging decision. It backfired on Freeman when he conceded that the officer who shot Clark acted within the law. Now BLM targeted Freeman. They disrupted his press conferences and protested at his home.

In July 2016, Hispanic officer Jeronimo Yanez shot and killed Philando Castile, a black man, during a traffic stop in Falcon Heights. After Castile informed Yanez he possessed a licensed handgun, the officer told him not to touch it. The situation quickly escalated as the officer ordered Castile not to “pull it out” several times before shooting him.

Ramsey County Attorney John Choi appointed independent counsel to review the case, and Yanez was charged with 2nd degree manslaughter. A jury acquitted him. Demonstrations ensued, but not to the degree Minnesotans would see in subsequent years.

The Castile case ushered in two troubling developments for the law enforcement community.

First, this was the first time in state history that an officer had been charged with a crime involving an on-duty shooting. It was clear that some prosecutors had now been influenced by the BLM narrative that police were targeting people of color, and it was their duty to correct this injustice.

Second, liberal politicians brazenly exploited the Castile case on the day of the incident without waiting for due process, well before any facts had been established. According to the Star Tribune, U.S. Sen. Al Franken stated, “I am horrified that we are forced to confront yet another death of a young African-American man at the hands of law enforcement. And I am heartbroken for Philando’s family and loved ones, whose son, brother, boyfriend, and nephew was taken from them last night.” And former U.S. Rep. Keith Ellison, current MN Attorney General, denounced the “systematic targeting of African Americans and a systematic lack of accountability” in the Washington Post.

Their words demonstrated how BLM was influencing citizens, law enforcement leadership, city leadership, elected county attorneys, and now state and federal political leadership.

The law enforcement community took notice.

Then came George Floyd. In an incident with world-wide notoriety in May 2020, Floyd had resisted arrest during a counterfeit bill complaint and died while in the custody of Minneapolis police. Floyd, a black man, was placed face down in handcuffs while officer Derrick Chauvin, a white man, kneeled on his shoulder and neck for nine minutes as police waited for an ambulance. Floyd eventually went into cardiac arrest and died.

All four officers at the scene were relieved of duty and charged with varying levels of murder and manslaughter in state court and civil rights violations in federal court — an extremely rare and arguably politically motivated move.

In three days, violence and lawlessness broke out in Minneapolis and throughout the nation as video of Floyd’s death, recorded by several bystanders, went viral. The focus of the world was on Minneapolis, and our political, legal, and public safety leadership seemed paralyzed.

Demonstrators descended upon the Minneapolis 3rd police precinct and the downtown government campus, which included the County Courthouse and City Hall. Roadways were shut down and businesses were looted and burned throughout the city. In an act of stunning capitulation, city and state leaders abandoned the precinct, enabling protesters to firebomb the station. Over two years later, the burned-out building sits vacant as a trophy to lawlessness.

BLM garnered significant support from cross-sections of Minnesotans in the days after Floyd’s death. It was common for officers who were holding security lines to be confronted by elected officials who had joined the protesters and were demanding the dismantling and defunding of police.

Law enforcement felt betrayed, and Minnesotans have paid a heavy price ever since.

The aftermath

While damage began to occur in our public safety institutions after the Jamar Clark case, it was unnecessarily widened in the Castile case, and completely ripped open in the Floyd case.

Many opportunistic progressive politicians called for the defunding and dismantling of law enforcement. Major corporations and individual donors, believing BLM’s narrative, donated millions of dollars to the organization in 2020.

In June of that year, Rep. Ilhan Omar told MinnPost, “I think there is an opportunity for them to, in dismantling and disbanding the Minneapolis Police Department, to really rid our society of the current form of policing that we have and put in place one that prioritizes crime prevention and community response.”

Many are now trying to walk back or at least mute the progressive position, but the damage has been done. “I think allowing this moniker, ‘Defund the police,’ to ever get out there, was not a good thing,” Ellison told CNN in November 2021.

The attempts to distance themselves from the movement many progressives helped create are not completely sincere. In a July 2022 Judiciary Committee hearing in Congress, N.C. Sen. Thom Tillis shared a website for ActBlue, a Democrat fundraising group. One of the group’s major fundraisers was a 13.12 mile run. The group proudly announced that the distance 1-3-1-2 corresponded to the letters A-C-A-B, which stand for “All Cops Are Bastards.”

Minnesota is now a state with a law enforcement community that is demoralized and critically understaffed, a court system that is exacerbating the problem by failing to keep criminals behind bars, a correctional system that inexplicably favors supervision to incarceration, and a political establishment that refuses to lead.

Effect on law enforcement

Minnesota is struggling with a dramatic drop in the number of law enforcement officers willing to stay on the job. Minnesota’s ratio of officers to citizens now stands at 1.9/1,000. The national average is about 2.8/1,000. Minnesota is arguably 5,000 officers below “average.”

Those who remain have pulled back into reactive mode instead of operating with the proactive mandate healthy communities provide their police.

Recruitment has also hit an all-time low, and most colleges are experiencing a decline in the number of students interested in law enforcement. Observers agree that this is likely to result in agencies hiring sub-par candidates — people who would not have made the cut in previous years.

The anti-police movement has simultaneously destabilized law enforcement and emboldened criminals. Since 2018, criminal offenses throughout Minnesota have increased 105 percent, while arrests have decreased by 57 percent. Another manifestation of the anti-police movement is a dramatic 165 percent increase in assaults against peace officers in Minnesota from 2017-2021.

System partners?

Sadly, the entire criminal justice system has overreacted to the pressures applied by the anti-police BLM movement. In the end, the system has failed to come together to address the rise in crime.

Progressive prosecutors are abdicating their responsibility to prosecute criminals. They have decriminalized swaths of crimes or declared legally obtained evidence from traffic stops off limits to their assistant prosecutors. Some sitting county attorneys, and several candidates for that office, have made “holding the police accountable” a top priority. But where, exactly, does holding criminals accountable factor in their list of priorities?

The courts have also failed to properly address crime in recent years, releasing far too many repeat offenders and violent criminals into supervision, where they can easily commit more violent crimes.

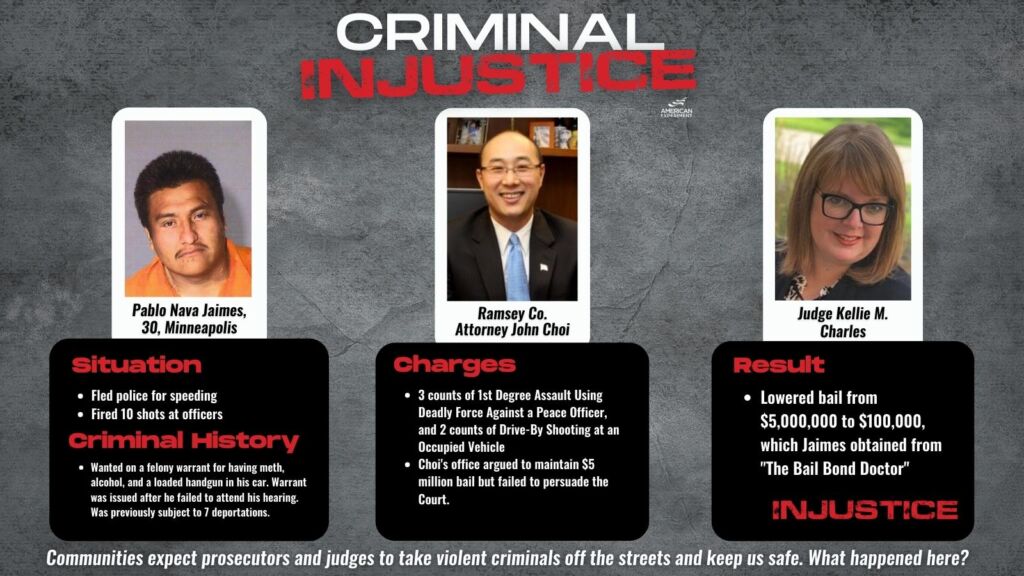

Consider the case of Pablo Nava Jaimes in Ramsey County. In June 2022, Jaimes shot at three peace officers while leading them on a high-speed chase through St. Paul and into White Bear Lake. American Experiment’s Criminal Injustice tracker illustrates how he was released on an abnormally low bail for such a crime, despite having been wanted on another warrant and having a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement record that included a reported seven previous deportations.

This points to a trend in which many in the criminal justice system believe it is their calling to fix societal issues through sentencing and correctional policy. This mindset ignores the fact that it’s far too late to effectively address societal issues once someone has been found guilty — not to mention that it arguably encourages more crime through a lack of accountability.

Yet, that is exactly what many judges attempt to do. Downward departures at sentencing are now occurring at an alarming rate. According to the Minnesota Sentencing Guidelines Commission, Minnesota judges departed down on a record-setting 43.2 percent of presumptive commitments in 2020 (sentences where the guidelines directed a prison sentence rather than community supervision). The two previous records were set in 2018 and 2019, respectively. This is an awful trend.

Correctional leaders have adopted this supervision-over-incarceration philosophy at the very time Minnesota is experiencing an historic spike in crime. Minnesota now ranks 48th in the nation for the lowest incarceration rate, despite rapidly rising crime rates.

Can Minnesota recover?

Law enforcement serves a vital role in maintaining peace and security in Minnesota communities. When police are attacked and devalued, and when their mandate is taken away, public safety suffers.

Unfortunately, Minnesotans have learned this lesson the hard way. Thankfully, there are signs that a healthy appreciation for law enforcement is returning.

- In a 2021 Thinking Minnesota Poll, 86 percent of respondents said they had total confidence in their local police to act in the best interest of the public.

- In a September 2021 Star Tribune poll, black respondents overwhelmingly rejected the notion that Minneapolis should reduce the size of its police force, 75 percent to 14 percent.

- Minneapolis voters followed up in November 2021 by rejecting their own city council’s efforts to eliminate the police department.

- A University of Massachusetts, Amherst poll found that support for the BLM movement’s goals had decreased from 48 percent in April 2021 to 31 percent in May 2022.

As columnist AJ Kaufman wrote in a July 2022 article for Alpha News, “To reduce violence in any community — Akron, Minneapolis, Chicago, wherever — residents must address the villains within their own community, not get sidetracked by hustlers who absolutely don’t want solutions. Anger is natural after a tragedy, and it’s much easier — but far less productive — to promote faux outrage than to seek peace.”

As civic leaders demonstrated in the 1990s, solutions to Minnesota’s crime problem require strong unwavering support for proactive law enforcement, a stricter judicial adherence to our sentencing guidelines, and a rejection of the current feeble levels of incarceration in the correctional community. Strong community resolve can achieve this, while strong unwavering leadership will maintain it.