The Marketfest rebellion

How local activists in White Bear Lake persuaded the Met Council to prevent 89 daily buses from cutting through their charming community.

On Thursday nights in the summer, the city of White Bear Lake is transformed into a mini State Fair, with thousands of people swarming its quaint downtown for its Marketfest celebration. The streets are shut down, live music blares from two stages and local restaurants and shops set up on the sidewalk, contributing to the lively and welcoming atmosphere. In a normal year, the most common question at the info booth is, “Where’s the petting zoo?” But in 2021 the most common question was, “Where do I sign the petition against the Rush Line?”

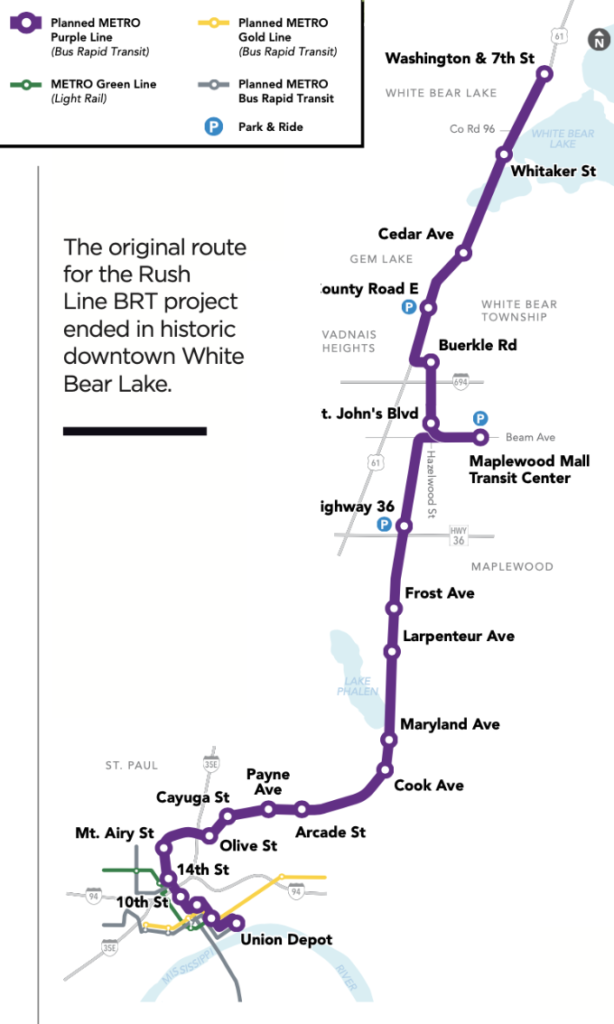

Rush Line refers to the 15-mile, 21-stop bus rapid transit project slated to begin at Union Depot in St. Paul, run through Maplewood Mall and end in downtown White Bear Lake. Ramsey County recently handed the project off to the Met Council where it has been re-branded as the Purple Line to better fit into the Twin Cities transit system.

Opposition to the Rush Line bus rapid transit project, previously bubbling under the surface, was about to manifest itself in a very public way at Marketfest. A group of strangers united in opposition to the line in early 2021 and formed the No Rush Line Coalition. They included regular citizens from Maplewood, White Bear Lake, White Bear Township, Vadnais Heights and Gem Lake.

“I tried very quickly to apply some organization to it because it wasn’t going to be a group of people who just wanted to vent,” David says.

Several in the group own homes in Maplewood with property backing up to the Bruce Vento trail. What is now a scenic, tree-lined bike and walking path will be clear cut to make room for the addition of a bus lane. Despite their literal Not-In-My- Backyard status, these homeowners are not the only ones objecting to the loss of trees and massive change to this heavily wooded trail. And the promise of quiet electric buses is hard to trust after the Met Council recently announced a plan to purchase 140 diesel buses over the next five years. A pilot program for electric buses was halted last year because of technical problems and concerns over cost and reliability in cold weather.

Other members of the No Rush Line coalition include taxpayers who simply object to yet another expensive transit project with dubious ridership projections. They watched the Southwest Light Rail project in the western suburbs come in $750 million over budget and the Northstar line in Anoka County lose 96 percent of its riders during the pandemic and worry the same will happen with the Rush Line.

But the strongest opposition to the project came from White Bear Lake residents who worried about how 89 buses a day driving to and through their historic downtown would ruin the city’s small-town character. It is the city’s biggest asset.

History of Rush Line

The Rush Line bus rapid transit project started in 1999 with a Rush Line Corridor Task Force composed of 22 elected officials from counties and municipalities along a corridor that followed Highways 61 and 35 from St. Paul to Rush Lake, Minn., (hence the name; it bears no reference to speed).

In 2009, the legislature allocated $3.4 million to study the Rush Line corridor. That’s always how it starts. A relatively small grant from the legislature to “study” a new project. An office is set up, engineers and planners are hired, and the work begins. After several years of study, the project grows to a point of inevitability: We’ve spent this much, we can’t stop now.

The total cost for construction of the Rush Line is $473 million with half coming from local or state sources and half expected from the federal government through a Fast Starts Grant from the Federal Transit Administration. Ramsey County will pay for the local share of construction via sales tax revenue dedicated to transit. Operational costs of $15 million per year will also be borne by Ramsey County taxpayers. Local planners must meet specific criteria for ridership, costs, and impact on the environment in order to receive federal funding.

As the route began taking shape, smaller decisions were presented to municipalities along the route. Should it be light rail or bus? What highways or streets should the route follow? Where will we put the stations or stops?

Some of these early decisions required votes. As a member of the White Bear Lake City Council, I objected to this cart- before-the-horse process in 2017 when Ramsey County brought a resolution to the council asking us to approve the locally preferred alternative route. Cities were being asked to approve the route without having a conversation about the overall project.

We were assured by Ramsey County the vote that day wasn’t for or against the overall project, just the route, if it was to be built. The vote approving the locally preferred alternative route passed the White Bear Lake City Council 3-2. It was the first of many 3-2 votes in favor of various aspects of the Rush Line project. Ramsey County and Met Council later used these votes as proof that cities like White Bear Lake approved the project multiple times.

The Marketfest awakening

As the project progressed through the different phases necessary to receive federal funding, community opposition started to build. Letters to the editor in the local White Bear Press expressed overwhelming opposition to the project. I wrote to the paper in April 2021 and asked for a “pause” in the project to review ridership numbers after the pandemic. I promised in that letter to have a city-wide conversation culminating with a municipal consent vote at a future council meeting. White Bear residents were challenging me not just to oppose the project, but to do something about it. Feedback in my council emails and conversations ran 9-1 against the line.

Response to the booth at Marketfest was overwhelming. The No Rush Line Coalition had six volunteers manning the booth with 150-200 people signing the petition against the line each of the four nights they were there. In addition to the petition, they sent 800 postcards to elected officials voicing opposition to the project.

“We didn’t know whether anyone would talk to us at Marketfest or what type of response there would be. If no one had talked to us, we would have gone away,” David says.

Armed with the knowledge about widespread opposition, the core group of the No Rush Line Coalition surveyed over 100 businesses along the proposed route and found 90 percent of them in opposition. They hosted booths at festivals, hosted pop-up events along the Bruce Vento Trail and created a fact-filled PowerPoint presentation with reasons to oppose it. At one point David emailed the presentation to Ramsey County staff asking them to verify the facts. “We wanted this group to be very fact based, which I think was important for our credibility,” he says. Staff made a few clarifications to the presentation, and David continues to share it with groups, business owners, and elected officials.

Businesses vote no

As the project moved forward, local business owners convened at the Best Western Hotel in White Bear Lake. Ramsey County project coordinator Andy Gitzlaff presented the plan for the proposed line and did his best to answer a barrage of questions from the skeptical audience.

“What are the ridership estimates?”

“We don’t have them yet.”

“How could you possibly build something this large and expensive without any data?”

Welcome to the world of government.

The public forum

On a Tuesday night last October, people filed into the upper floor of Kellerman’s Event Center in White Bear Lake. Big Wood Brewery and the Alchemist cocktail bar take up the lower level of this beautiful historic building in the heart of downtown, a few blocks from the second largest lake in the Twin Cities. Like many small Minnesota towns, White Bear gets its identity from the lake and began as a vacation destination for people from St. Paul looking for a quick getaway.

Kellerman’s was a fitting venue for a public forum to discuss whether a bus line that runs every 10 minutes from 7:00 a.m. to 10:00 p.m. is a good fit for such an historic and charming community. The owner, Terry Kellerman, one of the many business owners in the community against the project, was happy to offer his venue for the event. I cohosted the forum with the No Rush Line Coalition as a listening session, a chance for people to let us know what they think about the Rush Line project.

We set up 100 chairs, but quickly realized we’d need twice that number.

That 200 people showed up for a forum on a Tuesday night in October was more evidence that opposition to the project was strong and growing.

David walked through his PowerPoint slides and then opened the floor to public comments. The public forum received positive news coverage, which added momentum to opposition to the line.

“The public forum was a major milestone for us, and the idea of listening to people has been important throughout the entire effort,” David says. “We are not as much trying to persuade but trying to inform, and then listen to what their views are — and we’ve talked to and listened to thousands of residents.”

The 2021 election

In May 2021, Mayor Jo Emerson, a supporter of the project, announced she would not seek re-election, setting the stage for a mayor’s race with Rush Line as the number one issue. Rush Line opponent Heidi Hughes also announced she would challenge incumbent councilmember Doug Biehn, a strong supporter of the line. This was Biehn’s fourth race for council and the first time he had an opponent.

With momentum from the public forum, the No Rush Line Coalition, Marketfest and continued letters to the editor, Hughes defeated incumbent Councilman Biehn while Rush Line opponent Dan Louismet was elected mayor. Rush Line was the deciding factor in both races.

In February, the council held a two-hour work session on a strongly-worded resolution telling the Met Council “in the strongest of terms” to “modify the BRT Route so that it does not enter the jurisdictional boundaries of the City of White Bear Lake.” The resolution noted opposition from the community, poor ridership projections, and how it will “negatively impact the quaint, quiet, and walkable nature of the area.”

We expected to pass the resolution at our February 22 council meeting, given the new 3-2 anti-Rush Line majority. In a surprising plot twist, Councilman Steve Engstran, who had previously voted against Rush Line many times, announced he could not support the resolution the way it was worded. Engstran objected to the tone and length of the resolution and preferred something shorter and less political. The motion was tabled until March 8, and once again the citizen-led No Rush Line Coalition sprang to action delivering phone calls and emails to Engstran and the rest of the council. A modified resolution was brought forward, and this time Engstran joined Councilwoman Hughes and me in a 3-2 vote for passage.

Will the Met Council listen?

Throughout the years-long discussion of Rush Line, several of my colleagues on the council expressed frustration that the line was being foisted on White Bear Lake by Ramsey County and the Met Council. That was true. Until the pandemic, White Bear was serviced by Metro Transit Bus Route 265 with ridership of around 196 people a day from downtown, through Maplewood Mall to St. Paul. The route was canceled once COVID hit, and most Minnesotans started working from home.

While light rail projects require municipal consent votes from cities along the proposed route, bus rapid transit projects have no such requirement. In other words, the White Bear Lake resolution against the line was advisory only. The unelected members of the Met Council were under no obligation to listen to the city and stop the line at the city border.

But a surprising thing happened April 29 at the first meeting of the reconstituted Purple Line Corridor Management Committee, made up of local elected officials along the route and chaired by Charlie Zelle, chairman of the Met Council. Met Council staff went over the pros and cons of trying to build a bus rapid transit line in a city that doesn’t want it. The project would likely cost more and take more time without a city’s cooperation. The committee instead began discussion of alternative routes that do not include stops or stations in White Bear Lake.

The Met Council listened!

The project will continue with a different route that includes feeder buses running into White Bear Lake to pick up riders so they can join the Purple Line at the Maplewood Mall transit center.

The work is not over for the No Rush Line Coalition and Tim David, its leader. They plan to deploy the same strategies learned in White Bear Lake to convince the Vadnais Heights and Maplewood City Councils to oppose the line. Perhaps the Met Council will afford them the same courtesy they offered to White Bear Lake. No matter what happens in the future, David reflects on what’s been accomplished:

“It was a powerful message that communities can stand up to an organization like the Met Council, which is a behemoth with limited accountability and transparency, and make a difference in a community like White Bear Lake.”