The time bomb

This article is an adaptation of Martha Njolomole’s 2024 report “A Ticking Time Bomb: Minnesota’s vast and expanding welfare system.”

The consequences of Minnesota’s ballooning welfare system.

Transformational, but how?

A variety of words have been used to describe the 2023 Minnesota legislative session. Depending on which side of the political aisle you place yourself, the session was either “bonkers” or “transformational.” There is no denying, however, that the session was nothing short of extraordinary. Nowhere is that more evident than with the historic expansion of Minnesota’s welfare system.

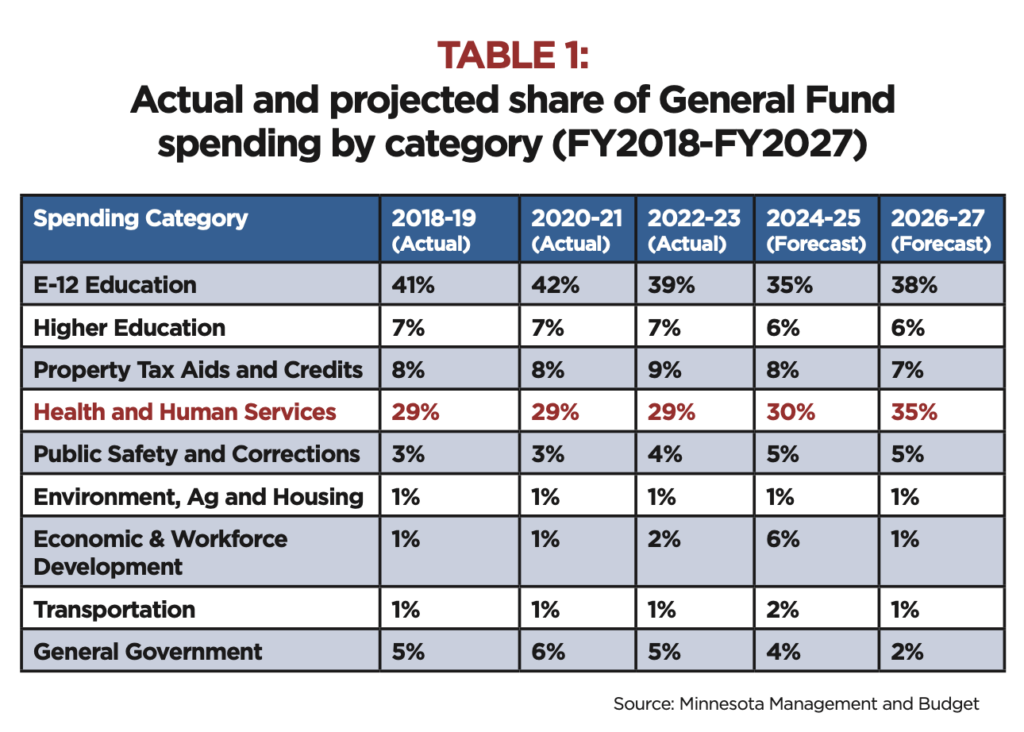

To be clear, the state’s welfare system wasn’t exactly modest to begin with. In the most recently ended two-year budgeting period between 2022 and 2023, for instance, 29 percent of the state budget went to Health and Human Services (HHS), most of it to fund numerous assistance programs administered by the Department of Human Services. And among the myriad public services on which the state spends money, HHS was, in fact, the state’s second biggest expenditure, surpassed only by E-12 education. HHS was the biggest expenditure, taking nearly half of all spending if we include money coming from the federal government.

But in the last session, under the claim of reducing costs for the most disadvantaged, Gov. Tim Walz and the DFL-controlled legislature used a portion of Minnesota’s staggering $18 billion surplus to ramp up welfare spending to an unprecedented level. As a share of the budget, HHS is expected to consume over a third of the state budget by the 2026-2027 budgeting cycle as shown in Table 1.

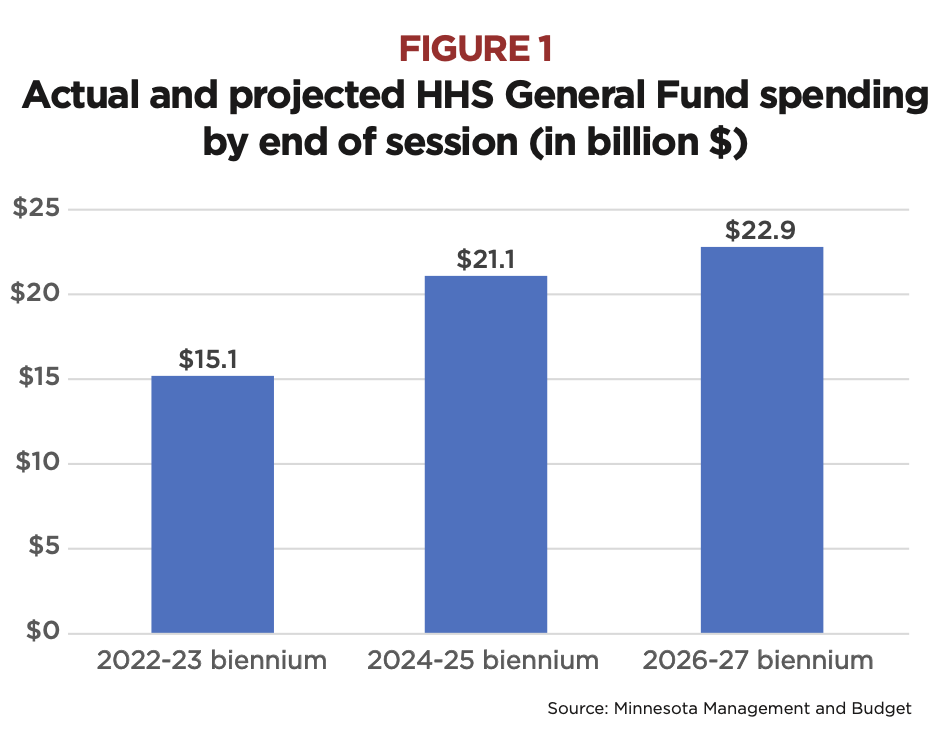

In dollar terms, Minnesota Management and Budget (MMB) recently estimated that HHS will grow by nearly $6 billion — or 40 percent — in the 2024-25 biennium compared to what it was in the 2022-23 biennium as shown in Figure 1. Spending will further increase by nearly another $8 billion — about 50 percent — in the 2026-27 biennium compared to the 2022-23 biennium. Put another way, in the four years covering the 2024 to 2027 fiscal years, $42 in every $100 of new spending in the budget will be allocated to HHS, making it the primary driver of growth within the state budget.

Minnesota’s welfare system has indeed undergone a “historic” expansion. But is that worth celebrating?

Transformative — but for better, or worse?

Compared to most states, Minnesota has historically had a generous welfare system. As a matter of fact, when Pres. Bill Clinton signed the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA) in 1996, declaring “the end of welfare as we know it,” Minnesota had long been experimenting with its own generous program to move people from welfare to work — the Minnesota Family Investment Program (MFIP).

The idea that government should prioritize moving people on welfare to work had taken root much earlier than 1996, both at the federal level and among most states. PRWORA itself was a culmination of work that started in the 1960s under John F. Kennedy, transforming the country’s main cash assistance program — Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) — from an entitlement program to one that required recipients to work, otherwise known as a “workfare” program. The most significant change is probably what came in 1981 when states were given the authority to establish their own “welfare-to-work” programs. From this, MFIP was idealized a few years later.

Minnesotans who had joined MFIP while it was in its pilot phase between 1994 and 1998 were especially lucky. While many states seemingly adopted a punitive approach to moving people off welfare, MFIP stood out for what many have described as a “compassionate” approach. The program combined strong work requirements with financial incentives and strong work supports, investing in job counselors, providing childcare to working parents, and helping with transportation. And, unlike AFDC, MFIP also let participants keep more of their incomes once they started working.

Since PRWORA effectively transformed AFDC into TANF (Temporary Assistance for Needy Families) and required that all states adopt some strict “welfare to work” programs to move welfare recipients into the workforce, MFIP shed some of its generosity partly to comply with new federal rules as it was converted from a pilot into a statewide program beginning in 1998. Still, Minnesota remained noticeably more generous than other states even after PRWORA.

According to the Urban Institute, for example, during the period between 1996 and 2000, Minnesota provided higher-than-average income benefits to TANF recipients, had a higher share of children in poverty receiving welfare, had a lower share of children without health insurance, had higher income cutoffs for its Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and had a higher income cut-off for childcare subsidy eligibility. And while in the two years between 1997 and 1999 welfare caseloads for cash assistance had declined by 42 percent after the passage of PRWORA, in Minnesota, the decline was only 30 percent.

Comparatively, Minnesota spends a bigger share of its budget on welfare programs than the rest of the country. Even after adjusting for the population in poverty, Minnesota ranks at the top when it comes to welfare spending. In 2019, for example, U.S. Census Bureau data shows that Minnesota spent an equivalent of $34,379 on public welfare per person in poverty. This is the third-highest spending rate among the 50 states, only behind Massachusetts and Alaska. The median state, on the other hand, only spent half that amount.

But even for a state as generous as Minnesota, the 2023 legislative session marked a stark departure from the traditional mantra that has long shaped welfare policy in the United States since the Clinton era: Welfare should not be a way of life, but rather a second chance. Unlike the reforms that came with PRWORA, which championed work and aimed to reduce poverty while also reducing dependence, the 2023 legislative session took Minnesota backward, prioritizing more spending above anything else. Eligibility limits for numerous programs have been loosened, widening the safety net for those not in dire need. Benefits were made more generous paired with eased income and work requirements for cash assistance. Lawmakers effectively paved the way for a larger swath of Minnesotans to enter the welfare system and remain in it for extended periods.

What happened in the legislative session

Take MinnesotaCare, for example. Historically, the program has provided subsidized health insurance coverage strictly to individuals whose incomes make them ineligible for Medicaid but is less than double the official poverty line. Last session, however, lawmakers passed a law that would potentially open the program to people with higher incomes beginning in 2027 (pending federal approval and other provisions) under what they call a “public option.” Lawmakers have also extended MinnesotaCare eligibility to undocumented immigrants, an option that will cost the state over $100 million between FY 2024 and FY 2027. Under Medicaid, lawmakers effectively wiped out cost-sharing for all Medicaid enrollees, including for high-income parents with disabled children who enroll in Medicaid under the Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act (TEFRA) option. This essentially puts taxpayers on the hook for the entire cost of Medicaid, which is expected to rise from $11 billion in the 2022-23 biennium to $17 billion in the 2026-27 biennium. Sure, some of the changes that legislators passed this session under the program are intended to bring Minnesota into conformity with federal changes. However, in true Minnesota fashion, lawmakers infused these new federal laws with a heavy dose of generosity, adding millions, if not hundreds of millions, in additional costs.

For example, when Congress passed the Consolidated Appropriations Act in December 2022, it mandated that beginning January 1, 2024, all states should provide continuous 12-month coverage to children under age 19 who qualify for Medicaid coverage, irrespective of whether they become ineligible for the program during those 12 months. The law passed to adhere to this requirement further extended coverage to young adults up to 21 years old. Lawmakers passed another law requiring that children who qualify for Medicaid while they are under six years old must remain on the program until they reach six years of age, regardless of whether they remain qualified to receive taxpayer-funded medical coverage.

Under cash assistance programs like General Assistance (GA), MFIP, and Minnesota Supplemental Aid (MSA), certain types of income would be excluded from the applicants’ countable income when determining eligibility for cash as well as childcare benefits. These include Retirement, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (RSDI) benefits and tribal per capita payments. Currently, hard-to-employ MFIP beneficiaries who have exhausted their 60-month lifetime limit must comply with MFIP requirements in their 60th month on the program, as well as “develop and comply with either an employment plan or a family stabilization services plan” to qualify for a hardship extension. However, beginning May 2026, only the latter condition will apply. Furthermore, penalties that are applied to recipients when they do not comply with work and training requirements in the MFIP program have also been significantly reduced, effective May 2026.

You should be concerned

Minnesota is not unique as a state with citizens, who, as Pres. Ronald Reagan described, “through no fault of their own must depend on the rest of us.” These include the disabled, the elderly, as well as working families who occasionally fall on hard times and need help getting back on their feet. But while our social safety net enables us to take care of these vulnerable individuals, the colossal expansion of the welfare system that lawmakers undertook in the last session will likely cause problems.

First, it is important to keep in mind that Minnesota’s government embodies numerous roles, and each state program competes for limited resources. With a larger portion of the budget going to the welfare system, little remains for other services fundamental to the health and well-being of our entire state, such as roads and public safety.

But even by itself, this new, bigger welfare system is already proving to be unsustainable. In the budget forecast released in early December 2023, for example, MMB estimated that tax revenues collected in 2026 and 2027 won’t be enough to cover the state’s bigger and growing budget. Ergo, there is a budget hole of over $2 billion. This is all thanks to our massive welfare system, which as of the beginning of the 2024 fiscal year, is the state’s fastest-growing spending category in the budget.

Taxes were already raised in the 2023 legislative session just to fund the state’s growing government — including its welfare system. But if the newly released budget forecast is anything to go by, taxes might have to be raised again if this new spending is going to be maintained into the future. The problem, however, is that even without accounting for the most recent tax hikes, Minnesotans were already paying some of the highest taxes in the country. That fact alone has been largely to blame for our economy’s mediocre performance in recent years. How these recently enacted tax hikes — and any other potential tax hikes in the future — will affect the economy is not hard to envision.

What’s possibly more grievous than the monumental fiscal burden that lawmakers have bestowed on taxpayers is the stark reality that the new system they have created does little, if anything, to give those on welfare “the opportunity to succeed at home and at work.” Instead of creating a system that fosters independence and success, lawmakers have been patting themselves on the back for transforming the state’s social safety net into one that turns an increasing number of Minnesotans into wardens of the state, irrespective of their actual need for assistance. And for those who are truly needy, legislators have settled for a less ambitious goal: making poverty more tolerable.

The vision of an end to welfare that Clinton touted remains an unrealized dream. Despite the watershed welfare reform bill of 1996, welfare spending has ballooned as money is funneled into other programs, such as Medicaid. More than the actual reform that it ushered in, the 1996 welfare bill presented an opportunity — a chance to reframe the nation’s welfare ethos away from entitlement towards a cherished American ideal: the conviction that meaningful employment is the most effective weapon against poverty. In many ways, Minnesota’s approach to welfare has diverged from this principle more than most states, and the recent 2023 legislative session has propelled us even further from this ideal. Minnesota has come around to a system the state attempted to discard nearly 30 years ago, one that exerts a heavy price on taxpayers without significantly assisting the poor to escape poverty and become self-sufficient. That is perhaps the greatest misfortune to come out of the 2023 session, one the effects of which will be felt for years to come, not only by taxpayers and welfare recipients, but the entire state economy.