Michael Shellenberger: China made solar cheap with coal, subsidies, and “slave” labor — not efficiency

The following article was written by Michael Shellenberger and originally appeared on Substack:

Until recently, many renewable energy advocates claimed that China had made solar panels so much cheaper than everybody else because of efficiency, automation in factories, and improved supply chains.

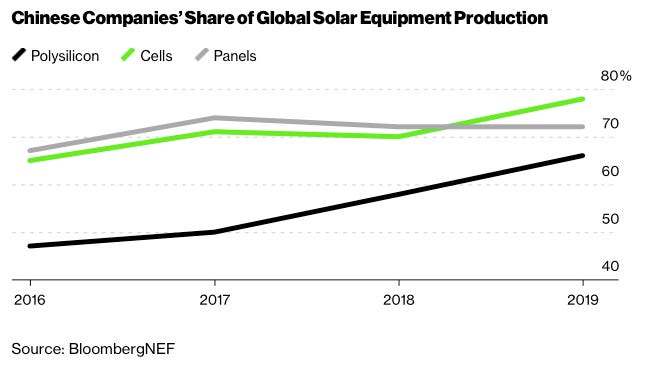

But events over the last few months make clear that the reason China came to dominate the market, producing 71% to 97% of solar panel components, is due to three main factors: cheap coal, heavy Chinese government subsidies allowing for the dumping of solar panels on foreign markets, and the use of forced labor in conditions the U.S. government representatives today describe as “genocide” and “slavery.”

It’s true that solar panels became more energy efficient, that the solar industry has been trying to automate, and that the Chinese make production efficient by successfully locating factories, mines, and power plants near each other. Goldman Sachs recently pointed to “higher module [solar panel] efficiency.” And The Financial Times’ Isabella Kaminska notes that when she visited a solar panel factory in Spain in 2004, it was “gearing up for automating.”

But the best performing models of the most common type of solar cells became just 3 percentage points more efficient during the decade that the cost of solar panels declined by roughly 75 percent, disproving the claim that panel efficiency was of much importance.

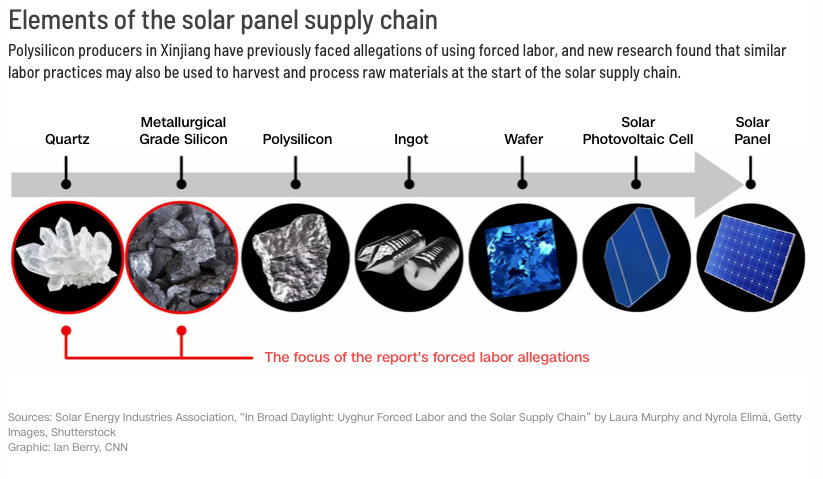

Goldman Sachs, in its same report, emphasized lower capital costs from “cheaper labour” were a key factor in China’s ability to lower costs, and the Chinese government admits that it operates “surplus labor” programs relocating millions of people from their homes in Xinjiang. It simply denies that it uses coercion in such relocations.

Moreover, there is little evidence the Chinese significantly automated its factories, which is why it has had to rely so much on forced labor. FT’s Kaminska posted photos of workers in solar panel factories creating panels by hand.

Part of the reason for that is because solar panels are so fragile and easy to break, notes Kaminska, citing a solar company report pointing to “the delicate nature of solar cells themselves. Around 0.3mm (0.011 inches) thick, they can be easily broken if not handled properly. As a result, production in the past has largely been dependent on manual handling. This slows down production and just a single misplaced thumbprint is enough to render a cell useless.”

And the Chinese government itself attributes its cheap solar panels to coal. “Over the past decade,” wrote a reporter for the web site, Global Times, which is a mouthpiece for the Chinese government, “Xinjiang has become a major polysilicon production hub in China, as the industry requires extensive amounts of energy, and that makes relatively cheaper electricity and abundant thermal power in Xinjiang appealing.”

In other words, China made solar panels cheap with coal, subsidies, and “slave” labor, not efficiency. Why is that?

Solar’s Dark Side

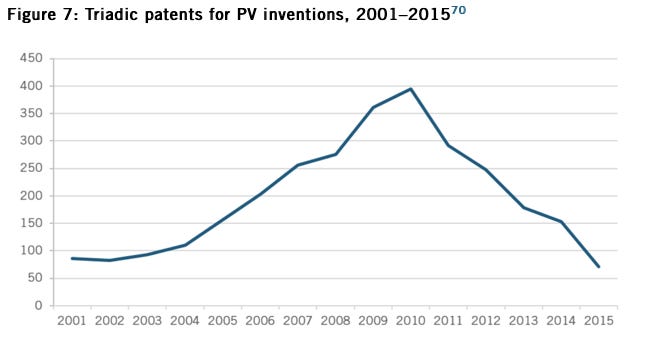

Solar panel advocates have long described the technology as innovative, but the dominant commercial solar panels today are the same crystalline silicon panels that Bell Labs developed in the 1950s. And patents for solar panels peaked in 2010, right as the Chinese were cornering the global market.

People thought a more innovative kind of solar panel known as “thin film” might be cheaper but it turned out to be even less efficient than the crystalline silicon ones. It requires more scarce and expensive materials and a more difficult manufacturing process. The most famous thin film firm, Solyndra, went bankrupt despite receiving a half-billion in US taxpayer money.

And against the picture of robots doing all the work, a new report finds that, “Manual laborers at Hoshine’s Xinjiang facility are paid to crush silicon manually at a rate of 42 Chinese yuan (around $6.50) per ton.”

While some have suggested that the production of iPhones is as brutal as the production of solar panels, it’s simply not the case. Workers in iPhone factories are not choosing to be there as an alternative to being in concentration camps.

Consider Hoshine, the biggest producer of metallurgical-grade silicon in the world. It is the primary material that is sold to the polysilicon makers. Hoshine’s factory, notes CNN, “holds two facilities that have been identified as detention centers for the ‘re-education’ of Uyghur people.”

Beyond creating a captive workforce, the Chinese government subsidies solar panel factories in other ways. In a profile of a solar panel maker in China in 2017, The New York Times documented its precarity and subsidy-dependence. “The suggestion that the government might cut the subsidy, even though the government did not follow through on it, panicked his investors,” reported the Times of one solar panel maker. “So they stopped financing further deals.”

Few deny that China sold solar panels on U.S. and European markets for less than it cost to make and ship them, which is called “dumping.” Both the U.S. and EU governments in 2012 and 2013 confirmed that Chinese government was subsidizing the dumping of solar panels.

“The fact that China’s major PV manufacturers have operated for the better part of a decade without making much money,” wrote a researcher for the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) last year, “suggests that subsidies continue to shape international competition in this industry.”

U.S. solar panel makers were forced to close because, even though solar energy receives significantly larger subsidies than wind, fossil fuels, and nuclear, they still could not compete with subsidized firms in China.

The US gave a 30% investment tax subsidy to US solar makers in 2009, as well as loan guarantees, including to Solyndra. “U.S. states also offered incentives to locate PV manufacturing plants within their borders,” notes ITIF. “But these, too, proved no match for their competition in China.”

Today, private investors shun new solar panel manufacturing because the profit margins are too low and the risks are too high. “Burned by their losses, and unwilling to enter a capital-intensive, low-margin business,” notes ITIF, “U.S. venture capitalists turned their attention elsewhere.”

In other words, the reason China had to make solar panels with coal, heavy subsidies, and forced labor was because cost reductions could not be realized by increasing efficiency. Solar cells are now within a few percentage points of their maximum theoretical efficiency, meaning that the best we can hope for from feasible, next-generation solar would still require 300 – 400 times more land than a nuclear or natural gas plant. And the low labor and land efficiency of solar are both due to the inherently dilute nature of the “fuel” for solar panels, sunlight.

Fleeing A Sinking Ship

Until this week, the Chinese government had hotly denied that it was using slave labor in its solar panel factories, just as it has denied that it is engaging in genocide, despite overwhelming evidence that it has put two million Muslim Uyghurs in concentration camps where they are subjected to forced labor and sterilization.

The Chinese government is now touting a single solar panel maker, Daqo. Wrote the reporter for Global Times, “after visiting the Daqo plant in Xinjiang twice and talking to workers freely in the past month, I found no signs of ‘forced labor’ in the factory at all. Instead, a high level of employee satisfaction and high wages at the company made it a sought-after job in the city, workers and local residents in Shihezi told me.”

Daqo’s CEO claimed not to have ties to Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps, or XPCC, the infamous government agency that oversees mass detentions. “We have no association with the XPCC,” Yang said. “We’re not owned by them.” The US Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control in 2020 imposed sanctionson XPCC “in connection with serious rights abuses against ethnic minorities.”

But the new report by British researchers I wrote about last week documented “a long-term, mutually beneficial relationship” between Daqo and XPCC and found that Daqo’s biggest suppliers had in fact hired forced labor from XPCC’s programs. “[Daqo’s] supply chain is tainted, and nobody’s going to look away from that anymore,” said one of the researchers.

And, noted Bloomberg, “Daqo has upheld the same secrecy as its peers with ties to the government-run labor program that’s under international scrutiny. As recently as March, the company declined interview requests for its executives and turned away foreign observers.”

Even so, Daqo, apparently with the blessing of the Chinese government, is on a PR offensive. The company is transparent about its motives, with Daqo’s chief financial officer telling Bloomberg that there is a “good probability” President Joe Biden will ban polysilicon made in Xinjiang, where the genocide is taking place. “We understand there are these perception risks, especially from the public and media, and some investors.”

“Daqo’s best bet is to try and win an exemption,” noted Bloomberg. “Chinese smartphone maker Xiaomi Corp. this month managed to get itself removed from a U.S. blacklist of military-linked companies, suggesting there’s a way for individual companies to avoid penalties even as tensions rise between the world’s two biggest economies.”

But the Chinese government can’t have it both ways. It can’t claim, on the one hand, that there is no slave labor being used in its solar panel factories, and that Daqo is unique in being free of slave labor.

When Bloomberg asked Daqo’s CEO about the concentration camps, he said, “Do they exist or not? Actually, I don’t know. But certainly if they do exist, then I think there are moral standards that this will be judged.”

Daqo thus found himself contradicting the Chinese government’s official position. “[CEO] Yang and his team plan to appoint an agency to conduct a human-rights audit of their operations—and most probably those of key suppliers—to back up the company’s assertion that it has ‘zero tolerance’ for forced labor,” noted Bloomberg. But why would such a thing be necessary if there is no genocide or forced labor at all being used in Xinjiang?

“Daqo’s push for transparency could also end up raising more questions about the other key players in the industry—Xinte Energy Co., GCL-Poly Energy Holdings Ltd. and East Hope Group Co.—and China’s labor practices in the region,” notes Bloomberg

And it is not clear how much permission Daqo got from the Chinese government before announcing its plans. “Conducting independent, third-party inspections at random times would require cooperation from a local government that has for years prevented foreign journalists and diplomats from freely visiting the region. Yang said the authorities have given Daqo ‘preliminary assurances’ that the auditors will be granted access.”

The Solar Energy Industries Association (SEIA) has urged its members to move out of Xinjiang, but such a move would not be easy, and it’s not clear how sincere SEIA is with its calls. JinkoSolar is on the board of SEIA, operates a factory in Xinjiang, and is the second largest buyer of polysilicon from Daqo.

Members of Congress have proposed Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act that would ban goods from Xinjiang unless the company importing them could prove that they were not made with forced labor, and the House of Representatives is considering a resolution calling the Chinese government’s actions genocide.

While claiming he will monitor and certify his factories, Daqo’s CEO “downplayed the importance of the American market,” said Bloomberg, “saying it only accounted for between 10% to 15% of the global market.

But more than the U.S. is considering a crackdown. Earlier this week, researchers for Germany’s Parliament (Bundestag) concluded that China is committing genocide against Muslim Uyghurs. This means German companies will almost certainly have to withdraw from Xinjiang and stop importing solar panels from China.

And if Germany bans solar panels made in China, then it is likely that the entire European Union will follow suit.. Whatever happens, the dream of solar energy as an innovative green industry is rapidly fading.

FT’s Kaminska was earlier than most journalists to see through the solar industry’s public relations. “The huge cost savings in the sector the last few years are as much about China using dirty coal and underpriced labour to produce solar as they are about any actual tech developments,” she wrote in 2018.

In her column today, Kaminska says. “We were quickly shot down by allegedly more informed Twitterati on the basis the industry was clearly highly automated.”

But now that it’s clear that China made solar panels cheap with coal, subsidies, and forced labor, Kaminska’s words proved prophetic. “History teaches us,” she noted back in 2018, “that there is no such thing as a free lunch.”

Please subscribe now to my Substack for a year-long discount, or click here to make a tax-deductible donation to Environmental Progress.