Michael Shellenberger: Stop Blaming Climate Change For California’s Fires. Many Forests, Including The Redwoods, Need Them

The following article originally appeared in Forbes. It was written by Michael Shellenberger.

Fires have burned 1.3 million acres of California’s forests over the last month. That’s one million acres more than burned last year, and is an unusually high number for this early in the fire season.

California political leaders including Governor Gavin Newsom and Senator Kamala Harris, the Democratic vice presidential candidate, blame climate change.

“If you are in denial about climate change, come to California,” Governor Gavin Newsom told the Democratic National Convention. “11,000 dry lightning strikes we had over a 72 hour period [led] to this unprecedented challenge with these wildfires.”

The New York Times NYT +0.5%, CBS News, and other news outlets have reported that the wildfires destroyed a forest of ancient redwood trees in Big Basin state park.

“Hundreds of trees burned at Big Basin Redwoods State Park,” reported Shawn Hubler and Kellen Browning for The New York Times. “Park officials closed it on Wednesday, another casualty of the wildfires that have wracked the state with a vengeance that has grown more apocalyptic every year.”

“The protected trees, some 2,500 years old, were nearly wiped out by loggers in the 1800s,” claimed CBS News’ Jonathan Vigliotti. “Now human-caused climate change has damaged or destroyed many of these ancient giants.”

“Big Basin Redwoods State Park has burned through,” reported New York Magazine’s David Wallace-Wells, pointing to climate change as the cause. “Some, older than Muhammad, had stood for a thousand years by the time Europeans set foot in North America. The youngest are older than the Black Death.”

But every school child who has visited one of California’s redwood parks knows from reading the signs at the visitor’s center and in front of the trailheads that old-growth redwood forests need fire to survive and thrive.

Heat from fire is required for the release and germination of redwood seeds, and to burn up the woody debris on the forest floor. The thick bark on old-growth redwood trees provides evidence of many past fires.

And, indeed, video footage taken by two San Jose Mercury News reporters, who hiked into Big Basin after the fire, shows the vast majority of trees still standing. What was burned up was the visitor’s center and other park infrastructure.

Video footage shows the vast majority of trees in Big Basin are still standing.

SAN JOSE MERCURY NEWS

Nor is it the case that California’s fires have “grown more apocalyptic every year,” as The New York Times reported. In fact, 2019 saw a remarkably small amount of acreage burn, just 280,000 acres compared to 1.3 million and 1.6 million in 2017 and 2018, respectively.

What about this year’s fires? “I see [the current California fires] as a normal event, just not one that happens every year,” Jon Keeley, a leading forest scientist, told me.

“On July 30, 2008, we had massive fires throughout northern California due to a series of lightning fires in the middle of the summer,” he said. “It’s not an annual event, but it’s not an unusual event.”

California’s fires should indeed serve as a warning to the public, but not that climate change is causing the apocalypse. Rather, it should serve as a warning that mainstream news reporters and California’s politicians cannot be trusted to tell the truth about climate change and fires.

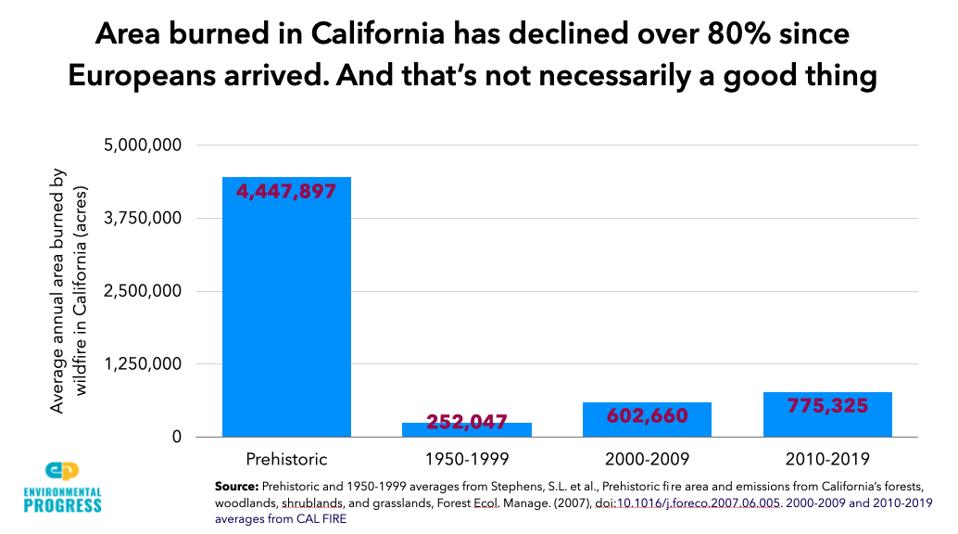

The area that burns annually in California has declined over 80% since the arrival of Europeans, and … [+]

ENVIRONMENTAL PROGRESS

It’s Not About The Climate

Nobody denies climate change is occurring and playing a role in warmer temperatures and heatwaves. Keeley notes that, since 1960, the variation in spring and summer temperatures explain 50% of the variation in fire frequency and intensity from one year to the next.

But the half-century since 1960 is the same period in which the U.S. government promoted, mostly out of ignorance, the suppression of regular fires which most forests need to allow for new growth.

For much of the 20th Century, U.S. agencies and private landowners suppressed fires as a matter of policy. The results were disastrous: the accumulation of wood fuel resulting in fires that burn so hot they sometimes kill the forest, turning it into shrubland.

The US government started to allow forests in national parks to burn more in the 1960s, and allowed a wider set of forests on public lands to burn starting in the 1990s.

“When I hear climate change discussed it’s suggested that it’s a major reason and it’s not,” Scott Stevens of the University of California, Berkeley, told me.

Redwood forests before Europeans arrived burned every 6 to 25 years. The evidence comes from fire scars on barks and the bases of massive ancient trees, hollowed out by fire, like the one depicted in The New York Times photograph.

“There was severe heat before the lightning that dried-out [wood] fuel,” noted Stevens. “But in Big Basin [redwood park], where fire burned every seven to ten years, there is a high-density of fuel build-up, especially in the forests.”

In 1904, three large fires burned Big Basin for 20 days, scorching the crowns of many trees, just as the 2020 fire did.

Reporters for The New York Times were apparently as pyrophobic 116 years ago as they are today, reporting that year that Big Basin, “seems doomed for destruction.”

But redwood forests regularly burn. A 2003 fire in Humboldt Redwoods State Park burned 13,774. Forest in 2008 burned over 165,000 acres. And a 2016 fire burned 130,000 acres.

Climate activists who in the winter excoriate those, like Senator James Inhofe, for pointing to snow as proof that global warming isn’t happening, turn around and point to summer fires as proof that it is.

“In my [five years] as a Californian,” wrote Leah Stokes in The Atlantic. “I’ve seen a years-long drought. I’ve evacuated my home as a wildfire closed in. I’ve lived through unprecedented heat waves…. that climate is no more.”

Environmental scholars scoff at this ahistorical view. “The idea that fire is somehow new,” said geographer Paul Robbins of the University of Wisconsin, “a product solely of climate change, and part of a moral crusade for the soul of the nation, borders on the insane.”

Fire Does Not A Hell Make

The amount of California that burns year to year is not uniform, Keeley emphasizes. “It was a mistake for the politicians in 2017 and 2018 to say ‘This is the new normal’ because 2019 was totally abnormal compared to 2017 and 2018.”

Is that amount abnormal? Not historically speaking. Scientists calculate that, before Europeans arrived, 4.4 million acres of California burned annually, which is 16 times larger than the amount that burned in 2019.

“Of the hundreds of persons who visit the Pacific slope of California every summer to see the mountains,” reported a U.S. government scientist in 1898, who had surveyed the region, “few see more than the immediate foreground and a haze of smoke.”

Even if 1.5 million acres of burned area per year indeed ends up being the “new normal” for a decade, it will still be one-third of the pre-industrial, pre-European average.

Why do activist journalists and politicians get California’s fires so wrong?

Part of the reason is their determination to blame climate change for everything.

“If all you have is a hammer everything looks like a nail,” noted Keeley. “If all you study is climate change than everything looks like it is caused by climate change. Every climate change research center finds climate is a problem. They are trying to find climate as the explanation.”

Climate bias is compounded by partisan bias. For example, journalists ridiculed President Donald Trump for suggesting that California’s fires were due to the state’s failure to remove undergrowth from its forests, even though scientists agree that the build-up of wood fuel through fire suppression is a massive problem.

Part of the problem is that many environmental journalists are so disconnected from the natural environment.

“I’m not an environmentalist,” confessed Wallace-Wells in his 2019 book, The Uninhabitable Earth, “and don’t even think of myself as a nature person. I’ve lived my whole life in cities… I’ve never gone camping, not willingly anyway…”

But if Wallace-Wells had been more of a “nature person” he might have known that fires are part of the cycle of life for redwood and many other forests.

The New York Times and other news media published a photo of a large, ancient redwood tree whose inner trunk is on fire. Many readers might have reasonably assumed the tree was dead, but that’s not necessarily the case.

In 1911, a reporter for the Santa Cruz Sentinel stood inside one of the trees hollowed out by the 1904 fire and noticed that it was still growing.

“To stand in the trunk of this tree and look up through the charred interior to the patch of blue sky far above, interlaced there with green branches, emphasizes the work of nature when producing the strange and awe-inspiring.”

The picture that Wallace-Wells and other activist journalists paint has more to do with religious depictions of a burning underworld than scientific descriptions of burning underbrush. “Looking from the vantage of today,” Wallace-Wells said last year, “we see that world and can think of it basically as a hell.”

Facts seem unlikely to get in the way of his desire to tell a good story. “Fires are among the best and more horrifying propagandists for climate change,” he notes, “terrifying and immediate, no matter how far from a fire zone you live.”