Migration data show that Minnesota is losing retirees as it is losing everyone else

As I noted yesterday, the Star Tribune carried an article last week by Evan Ramstad which provided a decent tour d’horizon of the economic debate in Minnesota. Titled “Guess what, Minnesota: Retirees are moving here, not leaving,” it refuted the idea that “Rich, old people are leaving because of [Minnesota’s high tax rates]…” Instead, it claimed, “retirees [are] moving to Minnesota like crazy:”

From 2020 to 2022, the latest year for which age-related census data is available, twice as many people over age 65 moved to Minnesota as people ages 18 to 65 moved out of Minnesota.

Mark Haveman, who leads the Minnesota Center for Fiscal Excellence, the nonprofit organization in St. Paul supported by business and respected by government leaders, made that discovery a few months ago. I double-checked his data this week.

After the 2020 census, 59,732 people older than 65 moved to Minnesota and 27,406 people in the working-age range of 18 to 65 moved away by summer 2022. That’s a net gain of 32,326 adults.

The Star Tribune‘s social media reported this as:

This was unthinkingly parroted by some of the state’s more credulous commentators:

I follow migration numbers quite closely. I have, myself, written that the common argument that Minnesota’s net loss of domestic migrants is dominated by retirees is wrong; that our state records net losses of residents in younger age categories, too.

But I was surprised to see that our state was such a magnet for those aged over 65. When a number surprises me, I try to recreate it myself.

Following the link in the article to the Census Bureau data, I was unable to locate anything relating to migration. What I did find was data relating to total population by age (Table SC-EST2022-SYASEX). Summing up the totals for those aged 18-65 and those aged 66 and over for both 2020 and 2022 and subtracting the former from the latter, I got sums of -27,406 for the 18-65 category and 59,732 for the category 66 and over: exactly those in the article.

But these numbers, to repeat, are numbers of total population, not migration. Total population might change as a result of migration, but it will change as a result of other things, too. At some point this year, Minnesota’s total population of 44-year-olds will rise by one, not because a 44-year-old has moved here but because I have had my birthday. Similarly, Nevada‘s population of over 65s fell by one last week, again, not because anyone had moved out, but because O. J. Simpson died.

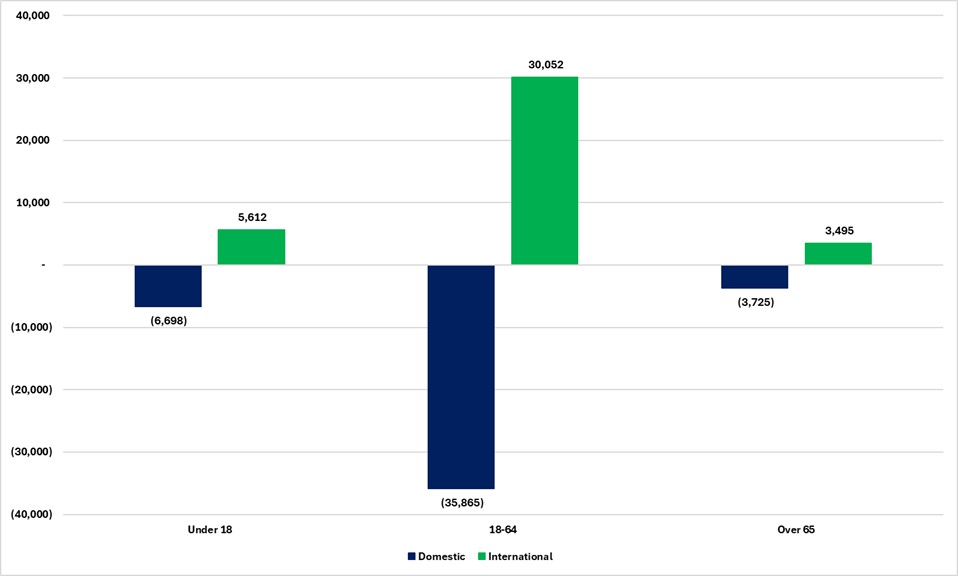

The Census Bureau does produce numbers for migration by age through its American Community Survey (accessible here). If we use those to look at migration into and out of Minnesota from/to other parts of the United States, we see, in Figure 1, that in 2021 and 2022, our state actually saw a net out migration among those aged 65 and over totaling 3,725 (Ramstad uses 66 and over but we are using 65 and over to bring this into line with commonly used categories, the results differ only marginally). Over the same period, Minnesota saw a net domestic out migration of 35,865 among those aged 18-64 and of 6,698 among those under 18. Some of this total net loss of 46,288 Minnesotans to other parts of the United States was offset by a net gain of 39,159 people from other countries, with gains in all three age categories.

Figure 1: Minnesota’s net migration by age, 2021 and 2022

I have absolutely no doubt at all that this is an honest mistake. Nevertheless, these migration data show us that retirees are not “moving to Minnesota like crazy,” or, if they are, more are moving out like crazy. On the more important economic point, however, that Minnesota is hemorrhaging residents in the prime of their working lives to other parts of the United States, the data show that Evan Ramstad is right, this is unequivocally the case. Figuring out why that is and what we can do to reverse it is one of Minnesota’s most pressing economic challenges.