More on the leak at the Monticello nuclear plant

On March 17, American Experiment detailed the water leak from Xcel Energy’s Monticello nuclear power plant that contained tritium, a mildly radioactive isotope of hydrogen that occurs naturally in the environment.

The leak continued to receive attention after Xcel announced that its temporary repair to the leaking pipe was not holding up, resulting in hundreds of gallons of tritiated water leaking from the plant. Rather than try another temporary repair, Xcel decided to power down the plant so crews could make permanent fixes to the pipes. The fixes are now complete, and the plant will be restarted next week.

This post will update the public on the latest status of the leak and give readers more insight into how groundwater flows work and the basics of hydrogeology that can help them understand why the leak does not pose a threat to public health or the environment.

The state of the leak

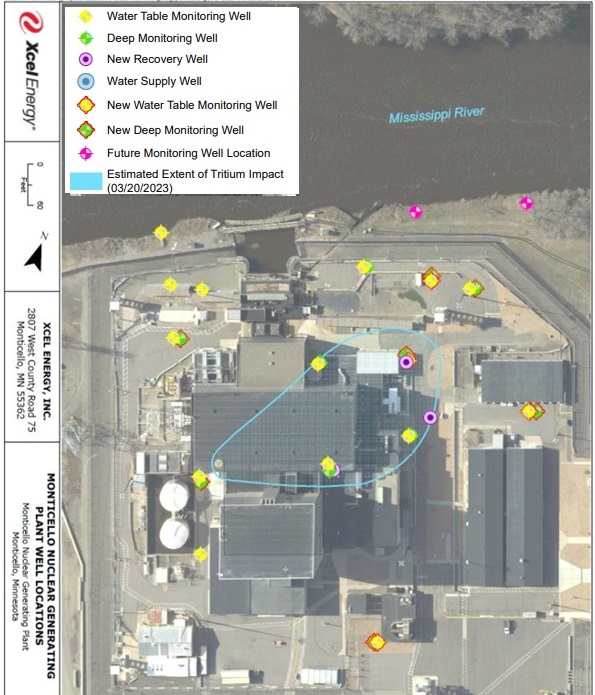

I wrote to Xcel Energy late last week asking if they had any diagrams of the leak to help illustrate it to the general public, and I am happy to report that they did just that.

The Monticello plant sits on the southern bank of the Mississippi River, as you can see in the diagram below. The blue teardrop-shaped area shows where the company believes water containing tritium has flowed through the groundwater.

Yellow dots show wells that monitor the water table, and green dots depict wells that extend further down to measure water quality at lower depths. The purple circles indicate new recovery wells. Xcel uses these wells to pump contaminated groundwater out from underneath the plant to prevent it from spreading further.

Yellow and green dots that are outlined in red are new wells that have been installed since the leak was first detected to give Xcel more information about the speed at which the contaminated water was flowing below the plant.

What it means for neighboring properties

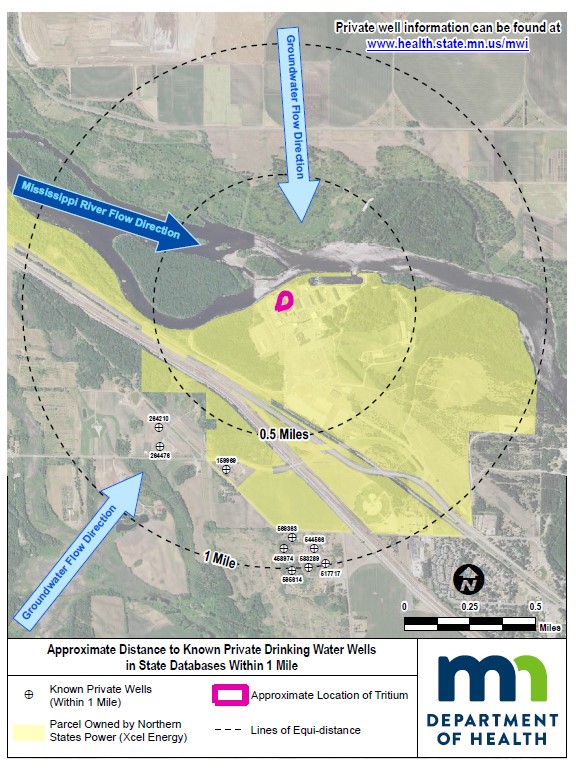

Like all water, groundwater flows from high to low-energy areas. Generally, this means that groundwater flows from areas of higher elevation to lower elevation. The Minnesota Department of Health map below shows that groundwater flows toward the Mississippi River.

This is good news for the property owners who live south of the Monticello plant because it means the tritiated water is flowing away from their water wells and toward the river. This flow is being held in place by the pumping wells, which draw water away from the river toward the plant.

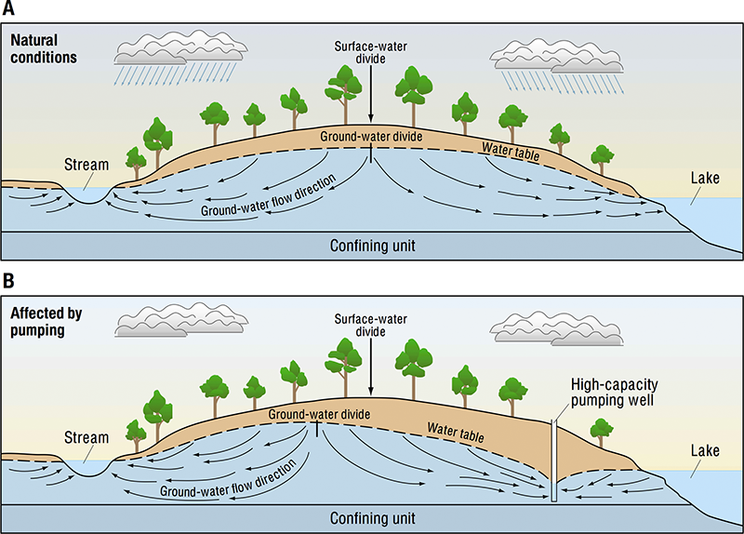

The cross sections below help demonstrate how this works in the real world.

Figure A shows groundwater flows under natural conditions. The groundwater flows from high-elevation areas to low-elevation areas, with the groundwater flowing toward the stream or the lake, depending on which side of the surface-water divide it is on.

Figure B shows how a high-capacity pumping well changes the direction of the groundwater flow around it. The pumping of the well draws down the water table, which is known as a cone of depression, and it changes the flow of groundwater away from the lake.

Therefore, pumping the groundwater at Monticello serves two important functions. One, it is keeping the teardrop from Figure 1 from reaching the river by changing the direction of the groundwater flow, and two, it has helped Xcel recover 32 percent of the tritiated water that has been released up to this point.

In a phone conversation with Xcel Energy representatives, they told me the company plans to continue pumping groundwater at the site for at least a year to recover more of the tritiated water and keep the plume from moving closer to the river.

The plant will power down again in mid-April for its normal refueling and maintenance schedule.